Dealing With Imbalanced Datasets The Easy Way

Imposing data balance in order to have meaningful and accurate models.

Introduction

Thanks for visiting my blog today!

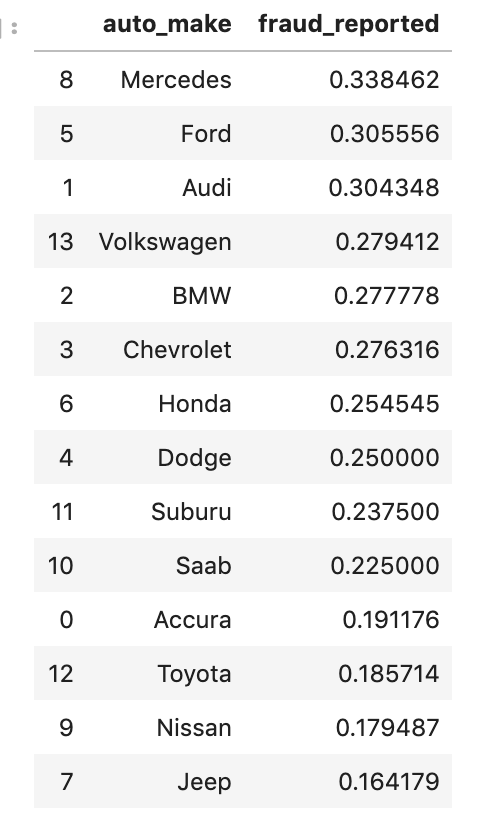

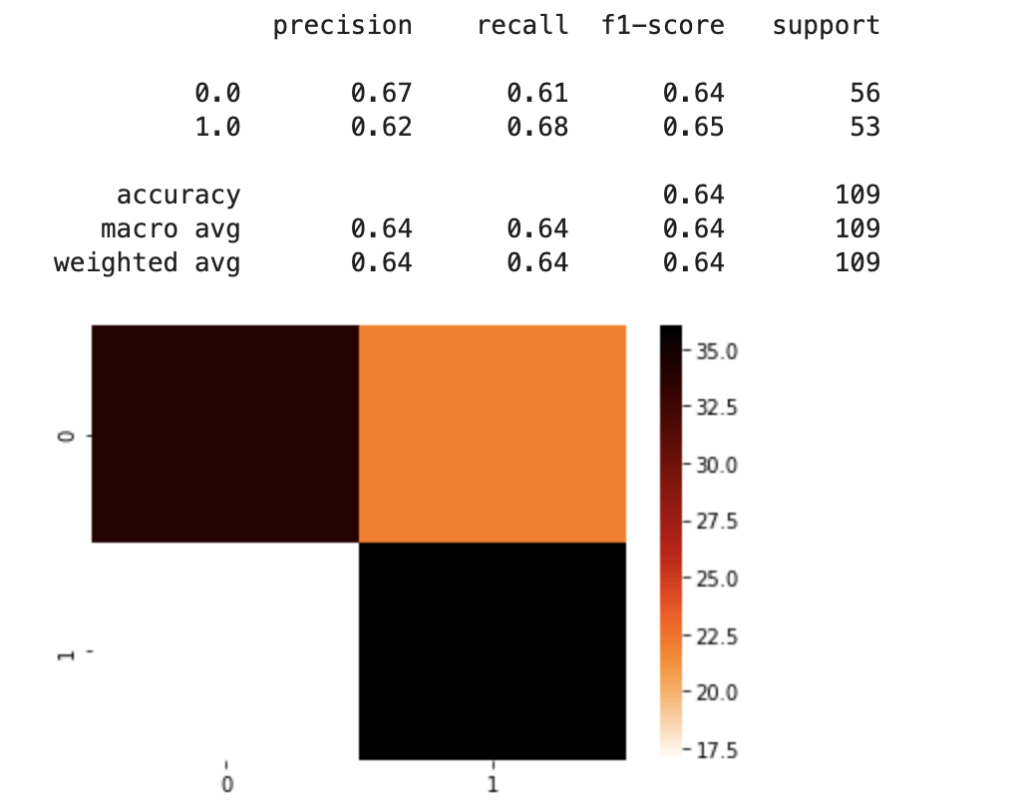

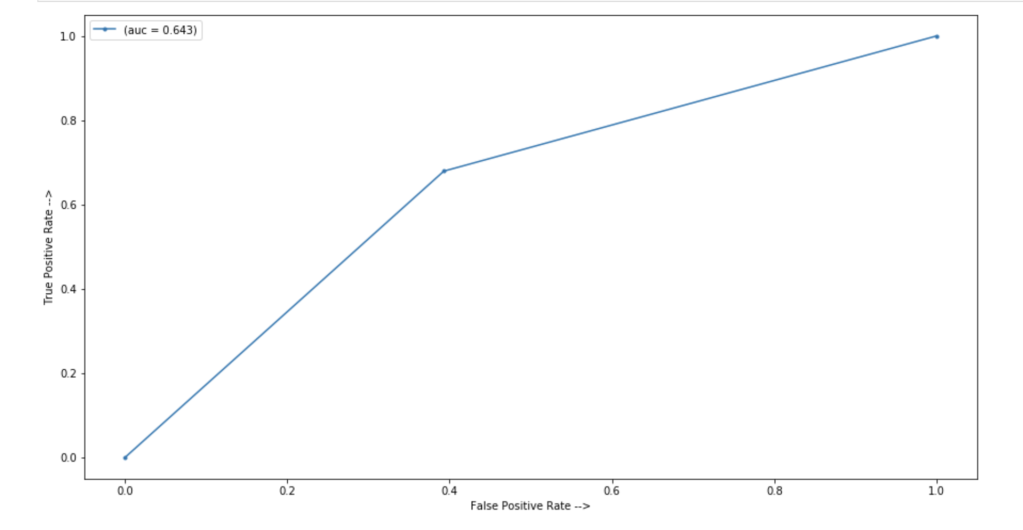

Today’s blog will discuss what to do with imbalanced data. Let me quickly explain what I’m talking about for all you non-data scientists. If I am screening people too see if they have a disease and I accurately screen every single person (let’s say I screen 1000 people total). Sounds good, right? Well, what if I told you that 999 people had no issues and I predicted them as not having a disease. The other 1 person had the disease and I got it right. This clearly holds little meaning. In fact, I would basically hold just about the same level of overall accuracy if I had predicted this diseased person to be healthy. There was literally one person and we don’t really know if my screening tactics work or I just got lucky. In addition, if I were to have predicted this one diseased person to be healthy, then despite my high accuracy, my model may in fact be pointless since it always ends in the same result. If you read my other blog posts, I have a similar blog which discusses confusion matrices. I never really thought about confusion matrices and their link to data imbalance until I wrote this blog, but I guess they’re still pretty different topics since you don’t normally upsample validation data, thus giving the confusion matrix its own unique significance. However, if you generate a confusion matrix to find results after training on imbalanced data, you may not be able to trust your answers. Back to the main point; imbalanced data causes problems and often leads to meaningless models as we have demonstrated above. Generally, it is thought that adding more data to any model or system will only lead to higher accuracy and upsampling a minority class is no different. A really good example of upsampling a minority class is fraud detection. Most people (I hope) aren’t committing any type of fraud ever (I highly recommend you don’t ask me about how I could afford that yacht I bought last week). That means that when you look at something like credit card fraud, the majority of the time a person makes a purchase, their credit card was not stolen. Therefore, we need more data on cases when people are actually the victims of fraud to have a better understanding of what to look for in terms of red flags and warning signs. I will discuss two simple methods you can use in python to solve this problem. Let’s get started!

When To Balance Data

For model validation purposes, it helps to have a set of data with which to train the model and a set with which to test the model. Usually, one should balance the training data and leave the test data unaffected.

First Easy Method

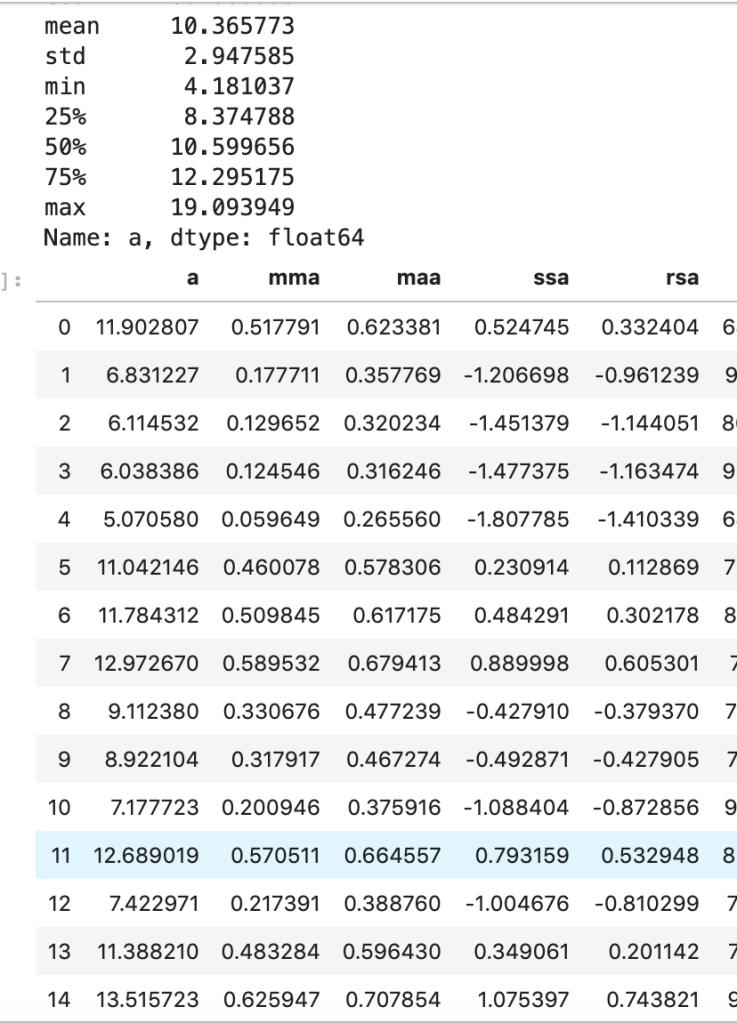

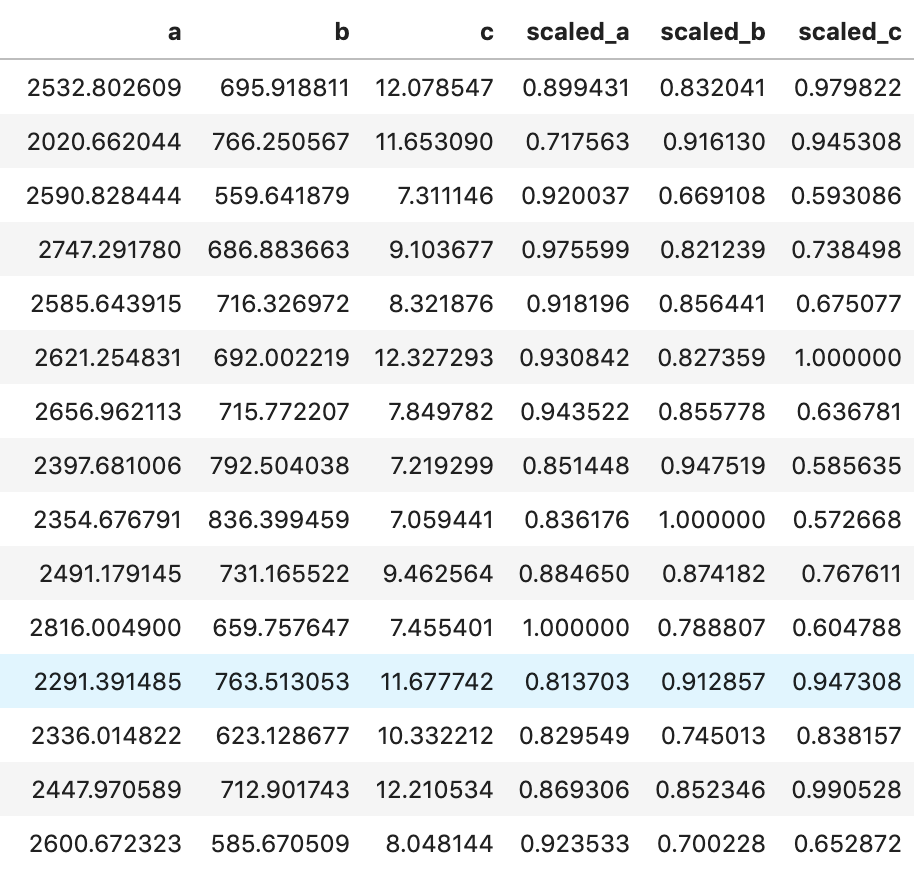

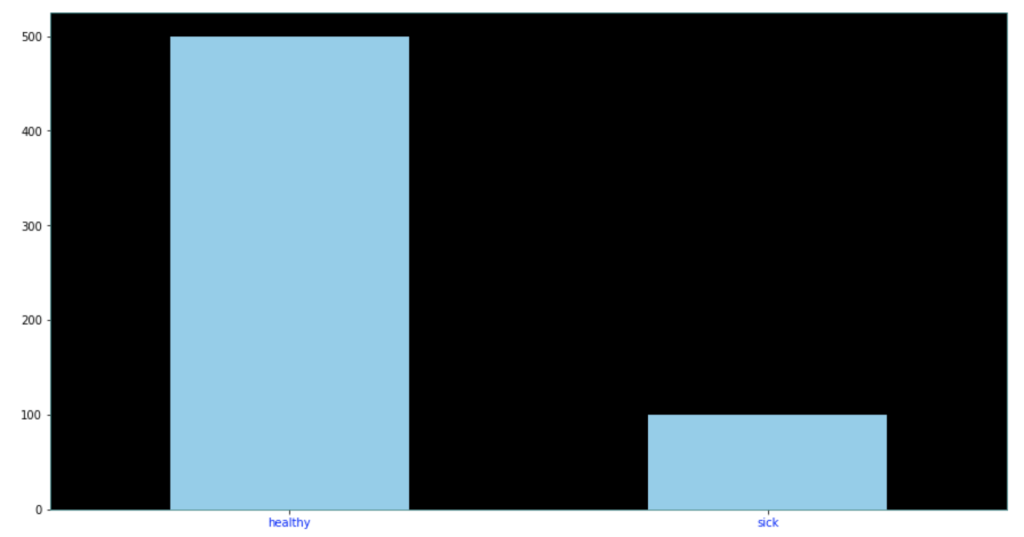

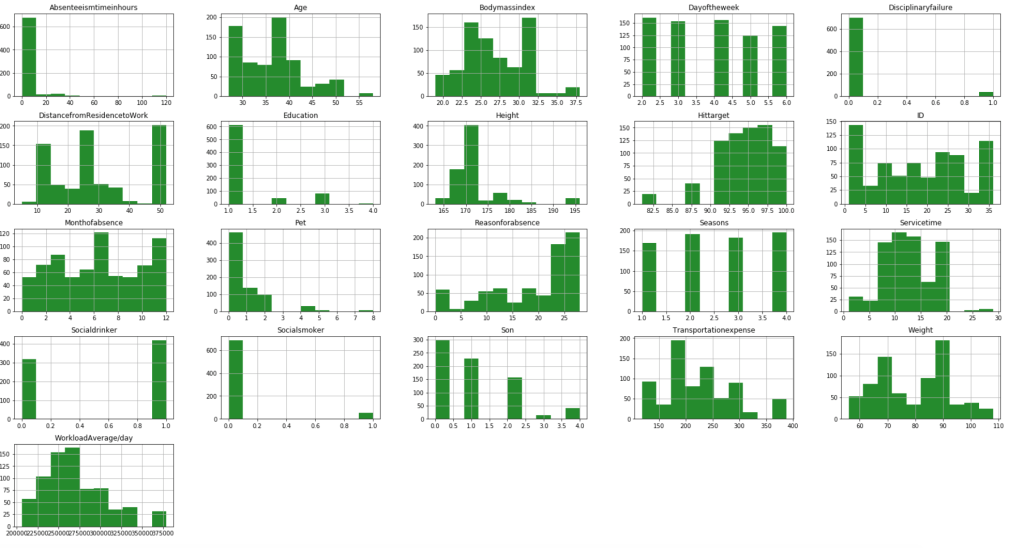

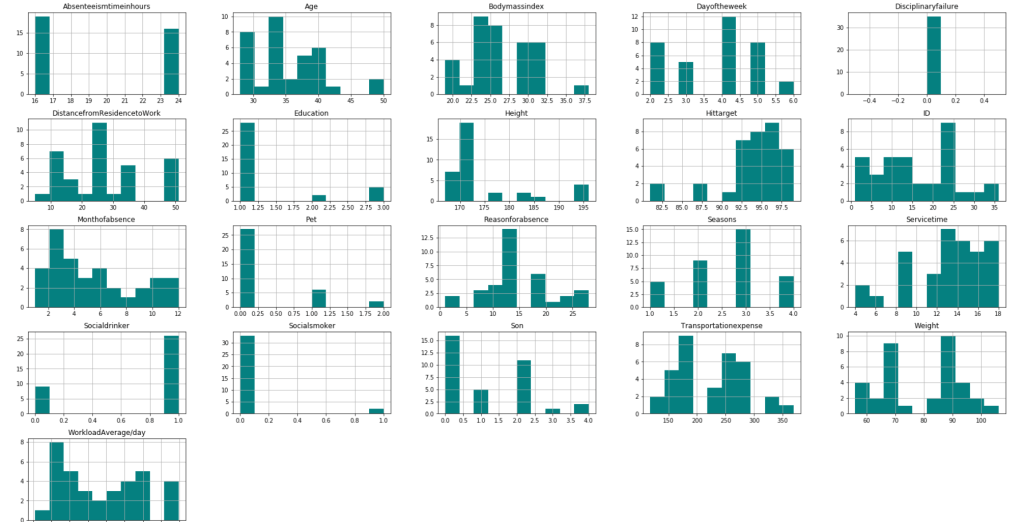

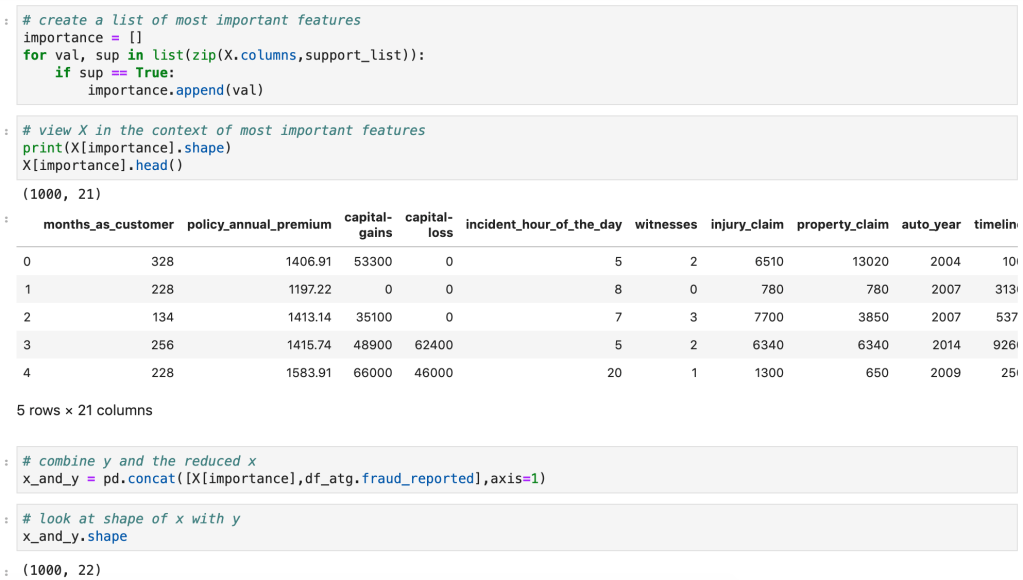

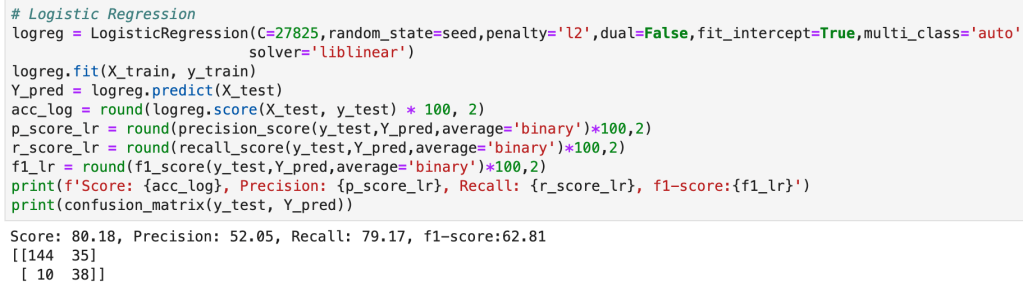

Say we have the following data…

Target class distributed as follows…

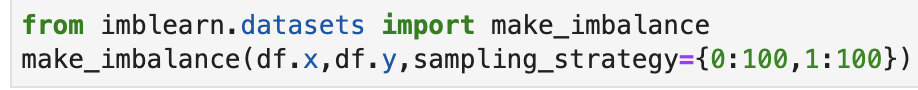

The following code below allows you to extremely quickly decide how much of each target class to keep in your data. One quick note is that you may have to update the library here. It’s always helpful to update libraries every now and then as libraries evolve.

Look at that! It’s pretty simple and easy. All you do is decide how many of each class to keep. After that, a certain number of rows resulting in one target feature outcome and a certain number of rows resulting in an alternative target feature outcome remain. The sampling strategy states how many rows to keep from each target variable. Obviously you cannot exceed the maximum per class, so this can only serve to downsample, which is not the case with our second easy method. This method works well when you have many observations from each class and doesn’t work as well when one class has significantly less data.

Second Easy Method

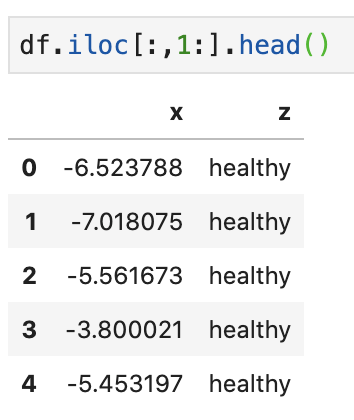

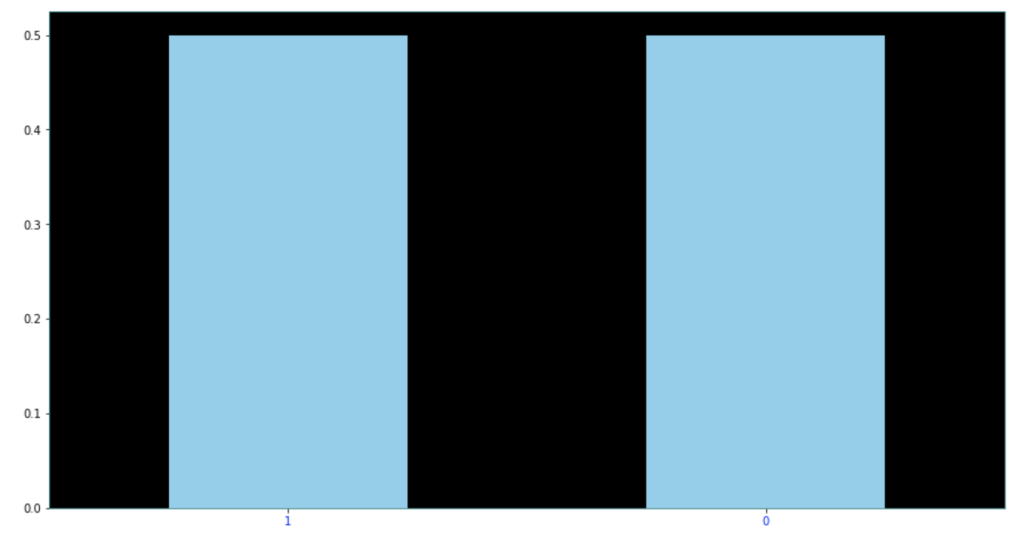

The second easy method is to use resample from sklearn.utils. In the code below, I decided to point out that I was using train data as I did not point it out above. Also in the code below, I generate new data of class 1 (sick class) and artificially generate enough data to make it level with the healthy class. So all the training data stays the same, but I repeat some rows from the minority class to generate that balance.

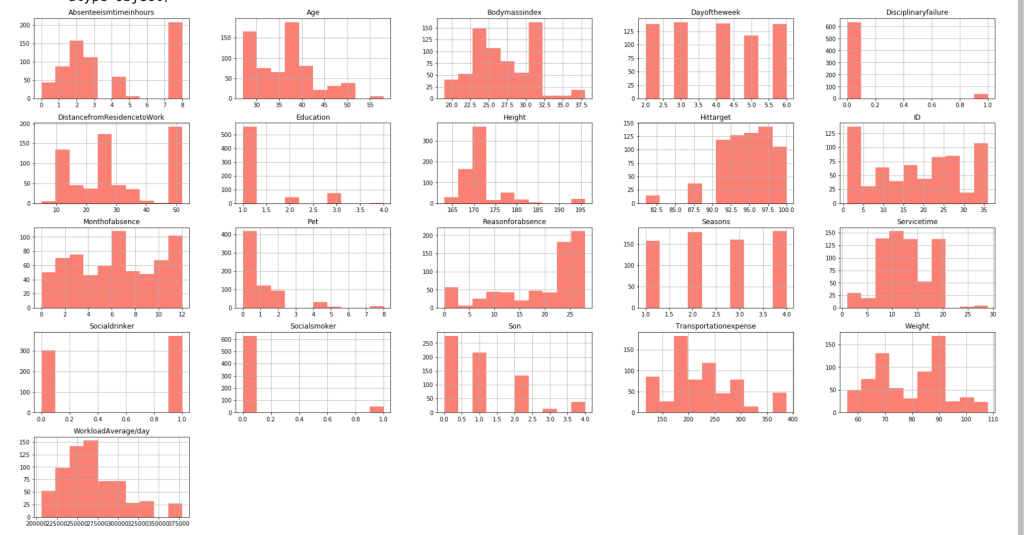

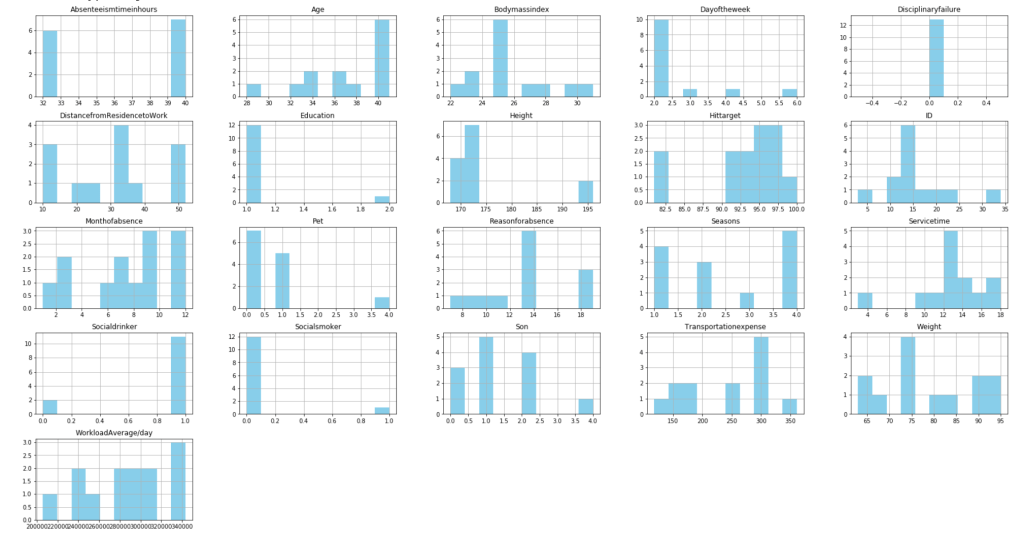

Here are the results of the new dataset:

As you can see above, each class represents 50% of the data. This method can be extended to cases with more than two classes quite easily as well.

Update!

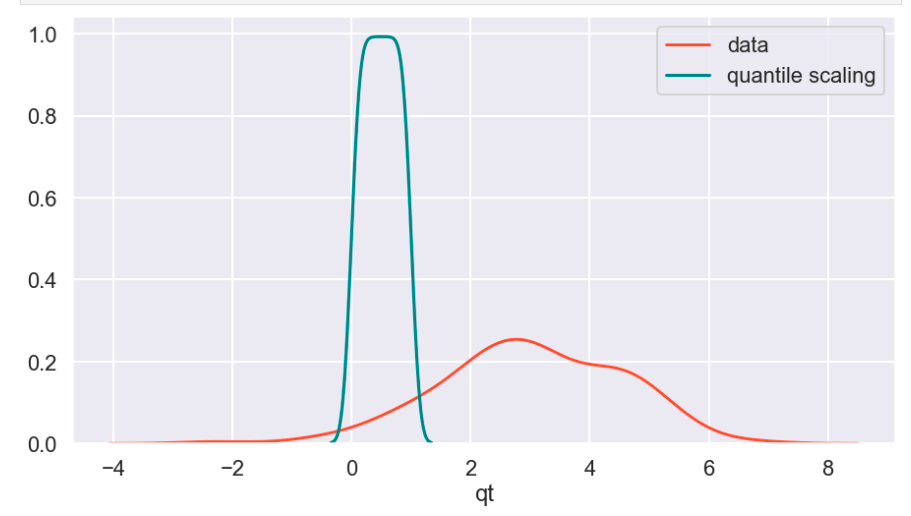

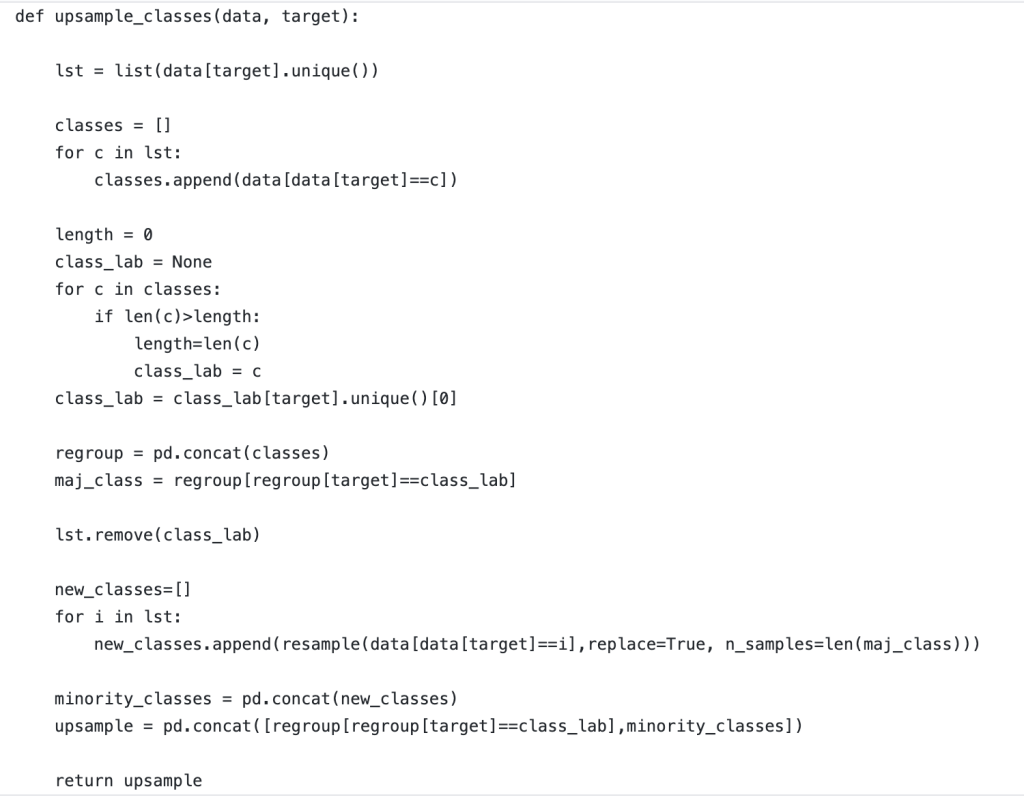

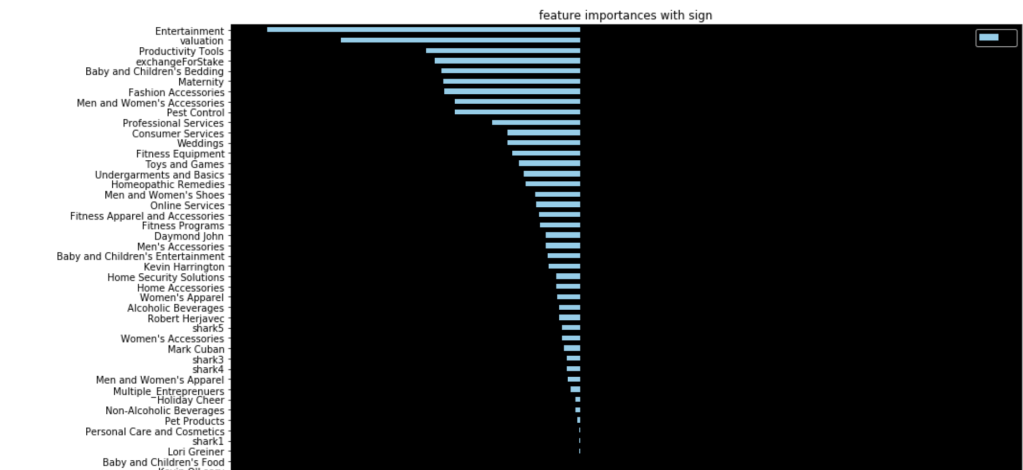

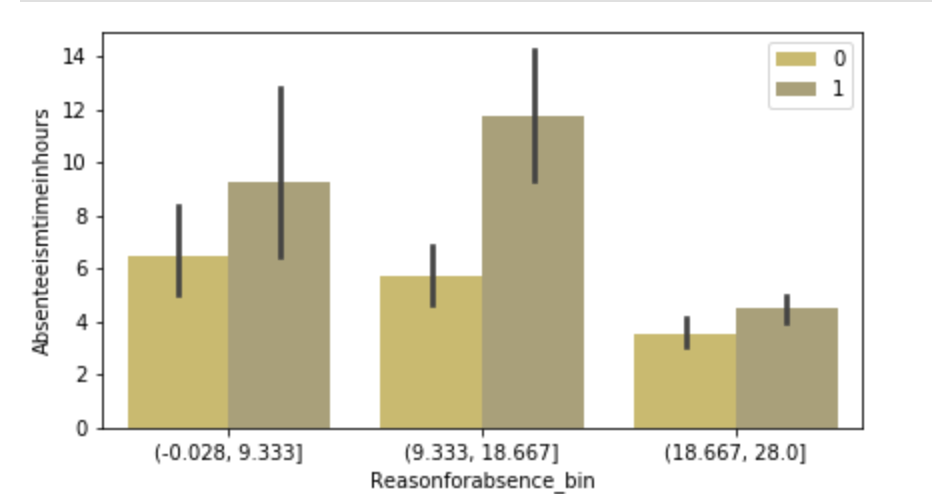

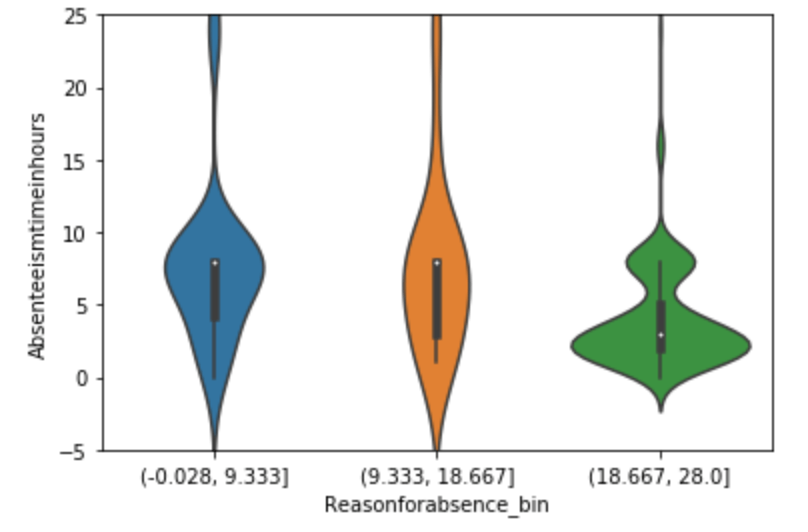

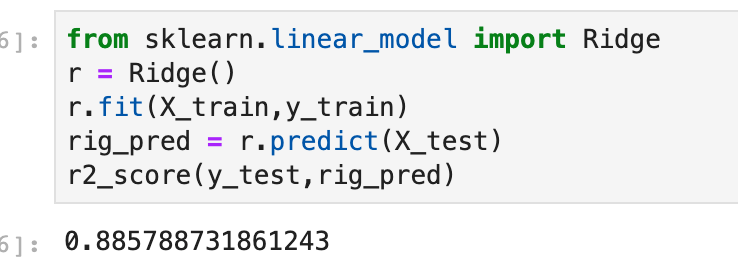

If you are coming back and seeing this blog for the first time, I am very appreciative! I recently worked on a project that required data balancing. Below, I have included a rough but good way to create a robust data balancing method that works well without having to specify the situation or context too much. I just finished writing this function but think it works well and would encourage any readers to take this function and see if they can effectively leverage it themselves. If it has any glitches, I would love to hear feedback. Thanks!

Conclusion

Anyone conducting any type of regular machine learning modeling will likely need to balance data at some point. Conveniently, it’s easy to do and I believe you shouldn’t overthink it. The code above provides a great way to get started balancing your data and I hope it can be helpful to readers.

Thanks for reading!

/close-up-of-thank-you-signboard-against-gray-wall-691036021-5b0828a843a1030036355fcf.jpg)