Pokemon: EDA and Battle Modeling

Exploratory data analysis and models for determining which Pokemon tend to have the biggest pure advantages in battle given no items in play.

Thanks for visiting my blog today!

Context

Pokémon is currently celebrating 25 years in the year 2021 and I think this is the perfect time to reflect on Pokémon from a statistical perspective.

Introduction

If you’re around my age (or younger), then I hope you’re familiar with Pokémon. It’s the quintessential Gameboy game we all used to play as kids before we started playing “grown-up” games on more advanced consoles. I remember how excited I used to get when new games would be released and I remember equally as well how dejected I was when I lost my copy of the Pokémon game “FireRed.” Pokémon has followed a basic formula running through each iteration of the game, and it’s pretty simple. It revolves around creatures known as “Pokémon.” You start with a “starter” Pokémon who usually has high potential but starts with very little power and you then can catch Pokémon, train Pokémon, buy items, beat gym leaders, find “legendary” Pokémon (I suppose the word “Pokémon” works as singular and plural), create a secret base, trade Pokémon with other gameboy owners, and of course – beat the Elite 4 like 500 times with different parties of Pokémon. With each new set of games (games were released in sets usually labeled by a color – silver & gold and green & red – as two examples), came a new group of Pokémon. The first generation was pretty bland. There were some cool ones like Charizard, Alakazam, and Gyarados but there were far more weird and boring ones like Slowpoke (Slowpoke has got to be the laziest name ever), Pidgey (second most lazy name?), and Arbok (Cobra backwards, yes it’s a snake). As the generations of Pokémon new to each set of games progressed there was a lot more diversity and creativity. Some generations like Gen 2 and Gen 3 really stuck out in my head. Examples include Skarmory and a special red (not blue) Gyarados in Gen 2 and Blaziken and Mightyena in Gen 3. The most important part of the Pokémon games are battles. Pokémon grow in skill and sometimes even transform in appearance through battling and gaining experience. You also earn badges and win prize money through battles. Battles are thrilling and require planning and tactics. This is expressed in many ways; the order of your Pokémon in your party, the type of Pokémon you bring to counteract your potential opposing Pokémon, the items you use to aid you in battle, when you choose to use certain moves (there is a limit to the amount of times each move can be used), switching Pokémon in battle, sacrificing Pokémon, diminishing the health of a “wild” Pokémon to the point where it doesn’t faint but is weak enough to be caught, and there’s a lot more I could probably add. Ok, so the point of this blog is to look for interesting trends and findings through visualizations in the exploratory data analysis section (EDA) and later I will examine the battles aspect and look for key statistics that indicate when a Pokémon is likely to win or lose a battle.

Let’s get started!

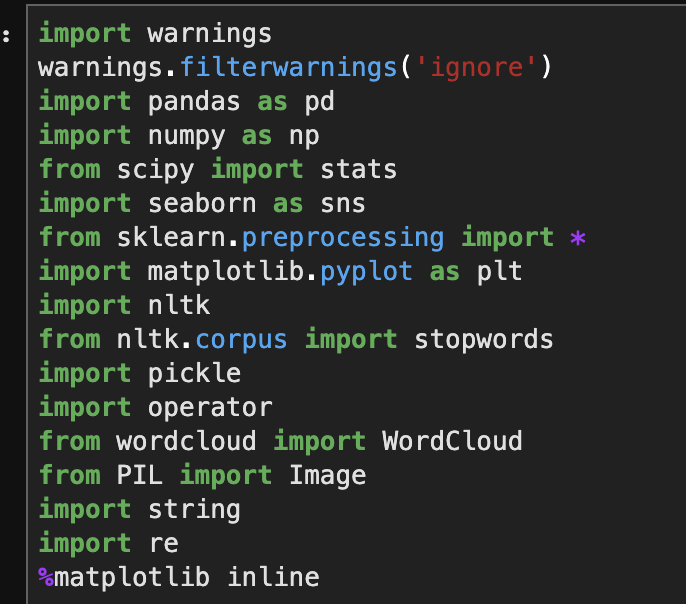

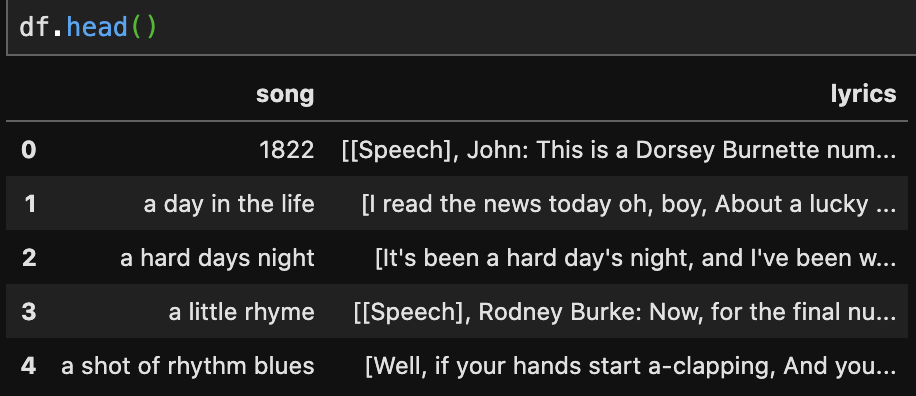

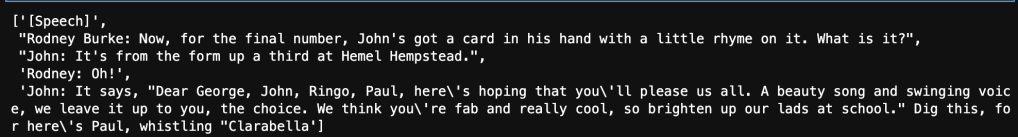

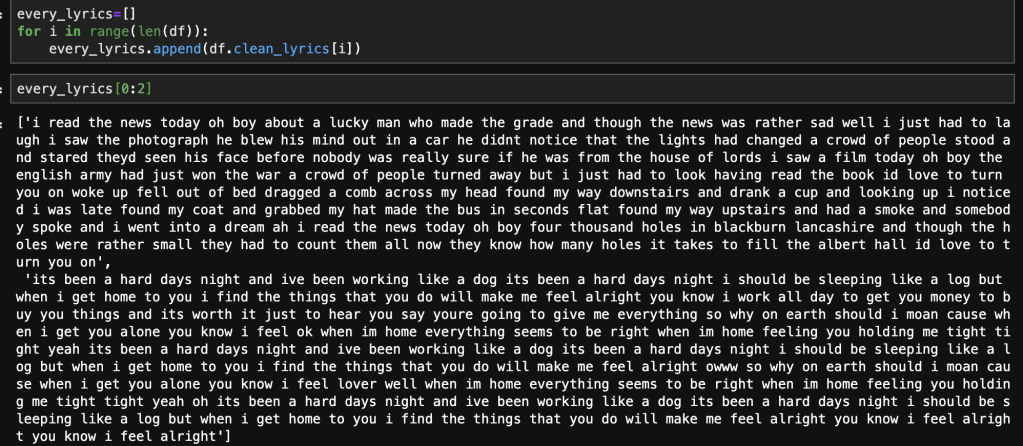

Data

My data comes from Kaggle and spans about 800 Pokémon across the first 6 generations of the series. I’d like to quickly note that this includes mega-Pokémon which are basically just more powerful versions of certain regular Pokémon. Let me show you what I mean; we have Charizard at the top of this post and below we have mega-Charizard.

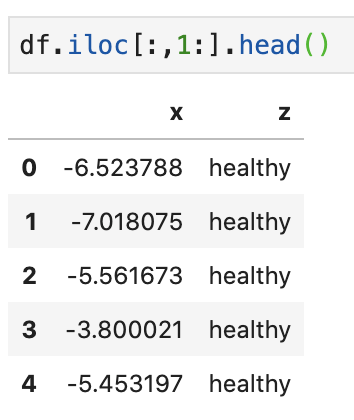

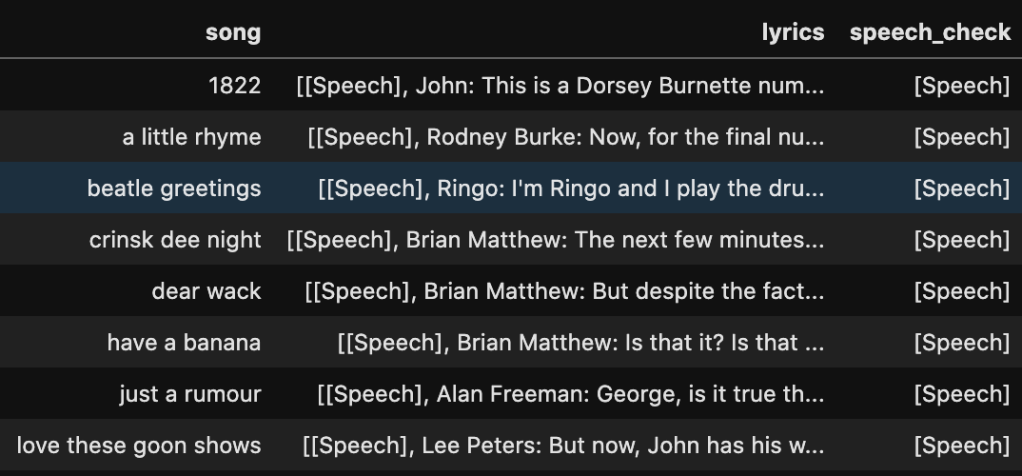

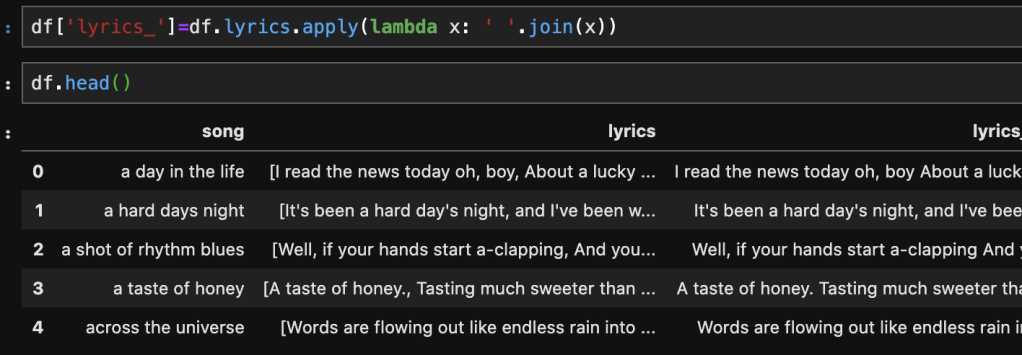

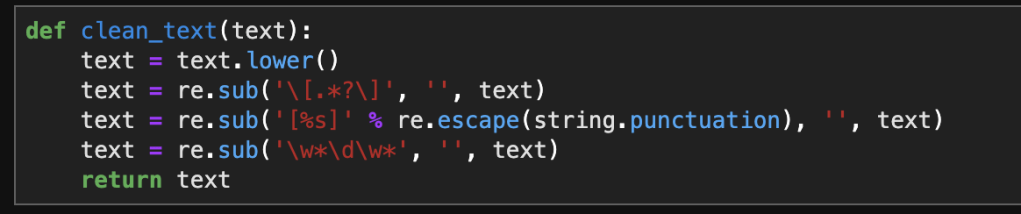

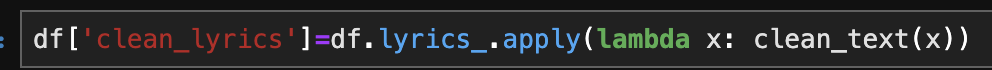

Yeah, it’s pretty cool. Anyway, we also have legendary Pokémon in this dataset but, while legendary Pokémon may have mega types, they are not a fancy copy of another Pokémon. I’ll get more into how I filtered out mega Pokémon in the data prep section. One last note on Pokémon classes – there are no “shiny” Pokémon in this data set. Shiny Pokémon are usually not more powerful than their regular versions but they are more valuable in the lexicon of rare Pokémon. Next, we have 2 index features (why not just 1?). Pokémon are by construction at least one “type.” Type usually connects to an element of nature. Types include grass, poison, and fire (among others) but also less explicit and nature-related terms such as dragon, fairy, and psychic. A Pokémon can have up to two types with one usually being primary and the other secondary. Type is a critical part of battles as certain types have inherent advantages and disadvantages against other types (fire beats grass but water beats fire, for example). Unfortunately, creating a dataset containing battle data between every possible Pokémon would be a mess and we therefore are going to use the modeling section to see what types of Pokémon are strongest in general, and not situationally. Our next features will be related to Pokémon stats. HP – or hit points – represent your health. After Pokémon get struck with enough attack power (usually after a couple turns), their HP runs out and they faint. This takes me to the next four features: attack, defense, special attack, and special defense. Attack and defense are the baseline for a Pokémon’s, well… attack and defense. Certain moves may nullify these stats though. A great example is a one-hit knockout move; attack doesn’t matter at all. Special attack and special defense are the same as attack and defense but refer to moves where there is no contact between Pokémon. So a move like “body slam” is attack-based while a move like “flamethrower” is special attack based. Total represents the sum of HP, special attack/defense, attack/defense and speed. Speed is a metric that basically determines who strikes first in battle. Occasionally some moves will take precedence and strike first but in the absence of those moves the turn-based battle begins with the attack of the faster Pokémon. The feature generation refers to which generation between 1 and 6 that the Pokémon in question first appeared in. Pokémon often make appearances in later generations once introduced in a previous generation. This is sometimes the case for legendary Pokémon as well. This takes us to our next feature which is a binary legendary Pokémon indicator. Legendaries are Pokémon that appear once per game usually in one specific spot that are generally quite powerful (and cool-looking). There are “roaming legendaries” that are unique but will appear at random locations until caught as opposed to being confined to one special location. Most legendaries are delegated to specific areas at specific points in a game’s storyline. Latios and Latias, from Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire are roaming and are incredibly hard to locate and subsequently catch while Groudon and Kyogre are easier to find and catch and play a key role in the storyline of their respective games. Finally, our last feature is win rate (and it’s continuous) – and that is the target feature. I added some features to the dataset which will be discussed below. The only one I’ll mention now is that I binned win rate into three groups in order to have a discrete model as well.

Data Preparation

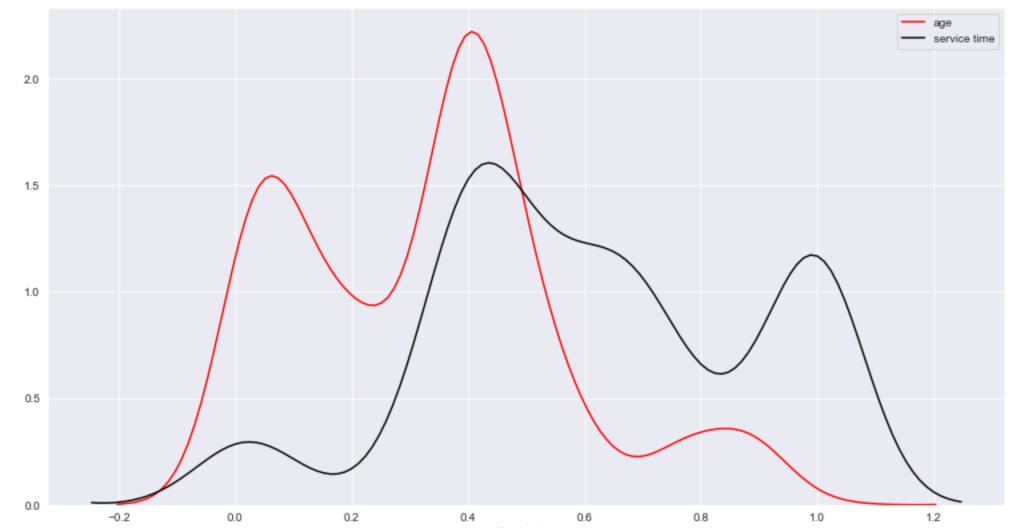

This section will outline how I manipulated my data for modeling purposes. I started by dropping extra columns like the index feature. Next, I created a feature which was a binary representation of whether a Pokémon was of one or two types. I also scanned the data to see if the word “mega” appears in any names and added a feature to indicate if a Pokémon was or was not a mega type. In addition to the collective data I also separated datasets into common, mega, and legendary Pokémon while aiming for no overlapping Pokémon. I had enough data where I could comfortably delete all rows with null values. I added another feature as well to measure the ratio of special attack divided by attack and did the same with defense. I originally thought special attack meant something different than what it actually means and ended up calling these features “attack bonus” and “defense bonus.” Next, I filtered out any rows containing numerical outliers which would be 2.5 standard deviations away from the rest of the data in said feature. This reduced my data by about 15%. Next, I applied max-absolute scaling to gauge the value of each data point relative to the other values in each feature (this puts every result somewhere between 0 for low and 1 for high). I also noticed through hypothesis tests that speed might have an outsized impact on battle outcome (more on this later) so created an extra feature called “speed ratio” to reflect how much of a Pokémon’s total comes from speed alone. To deal with categorical data, I leveraged target encoding. I published an article on Towards Data Science which can be found here if you would like to learn more about target encoding. This was the end of my main data prep. I did a quick train-test-split which pertains more to modeling but is technically an element of data prep.

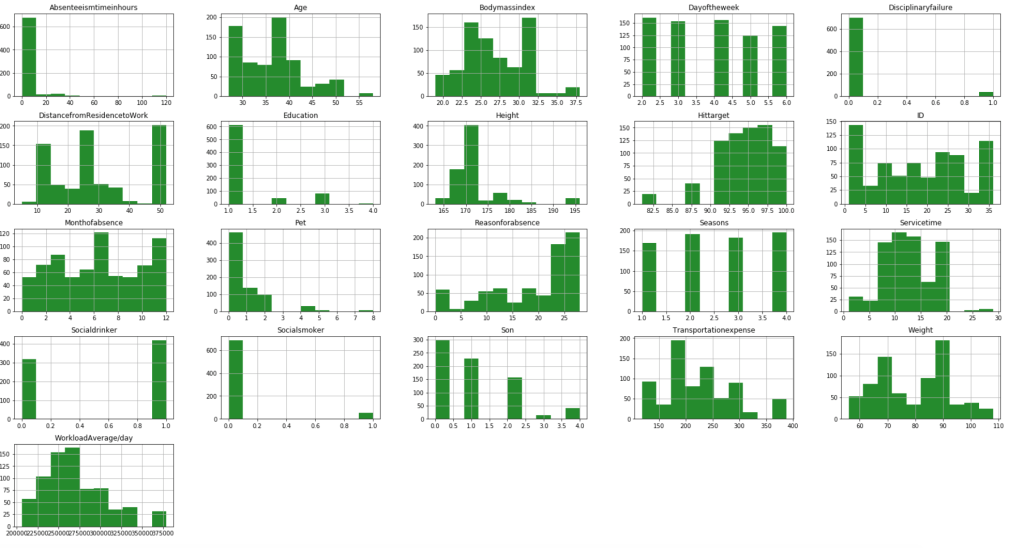

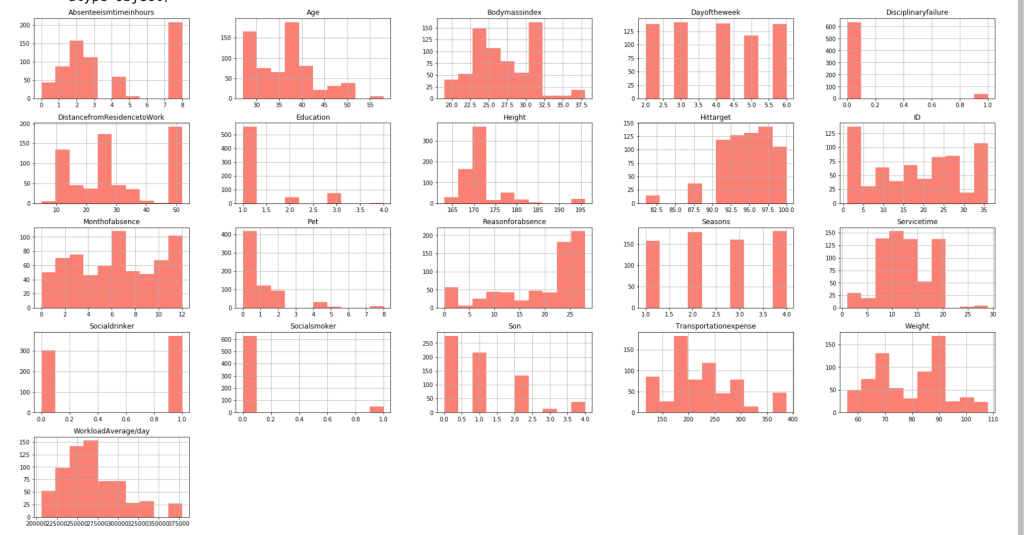

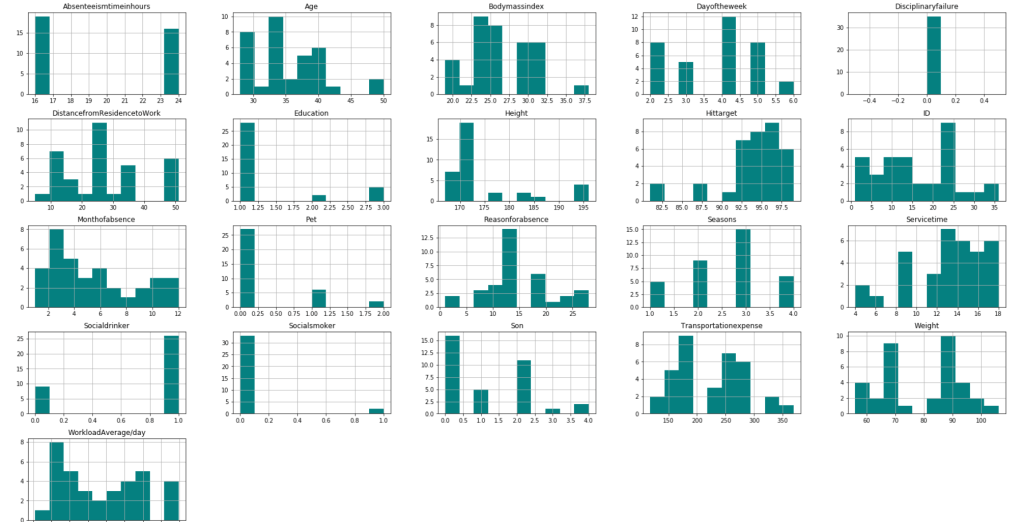

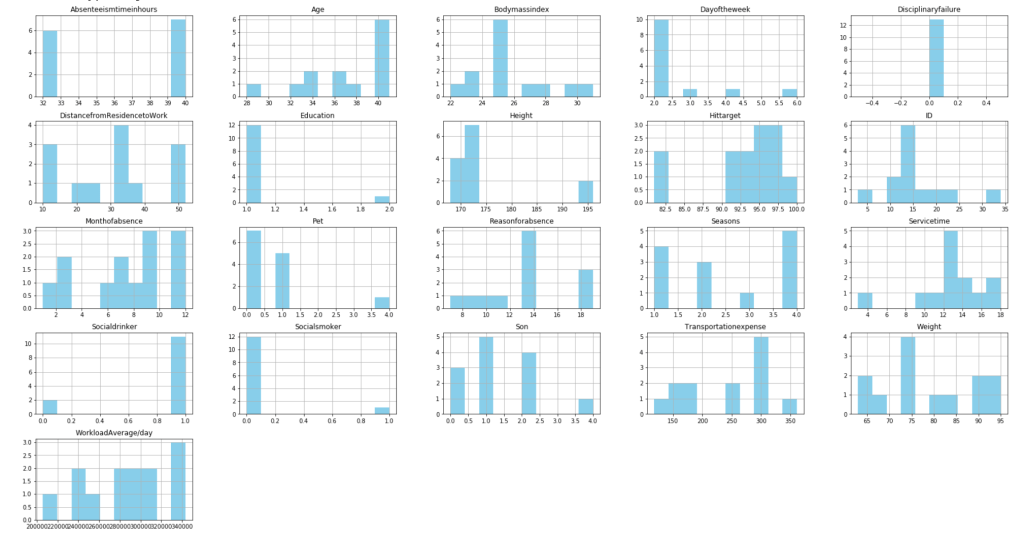

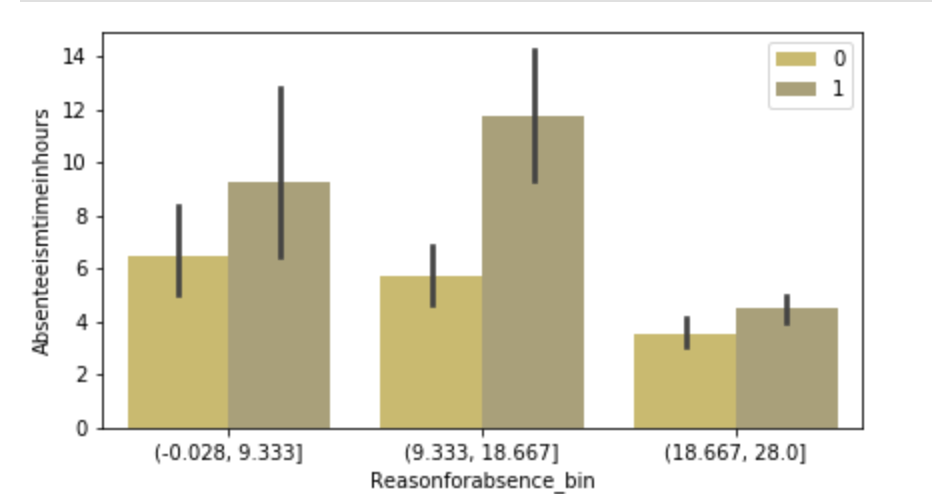

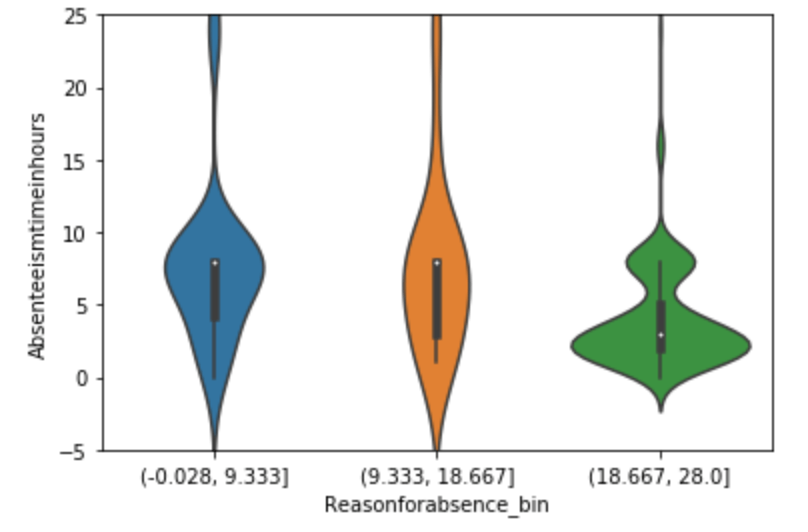

EDA

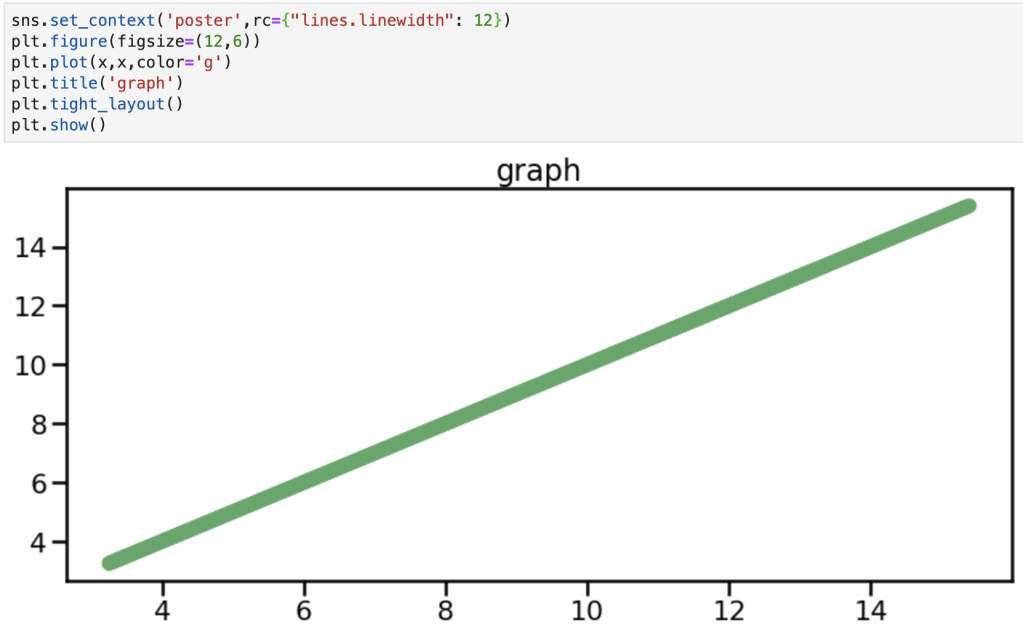

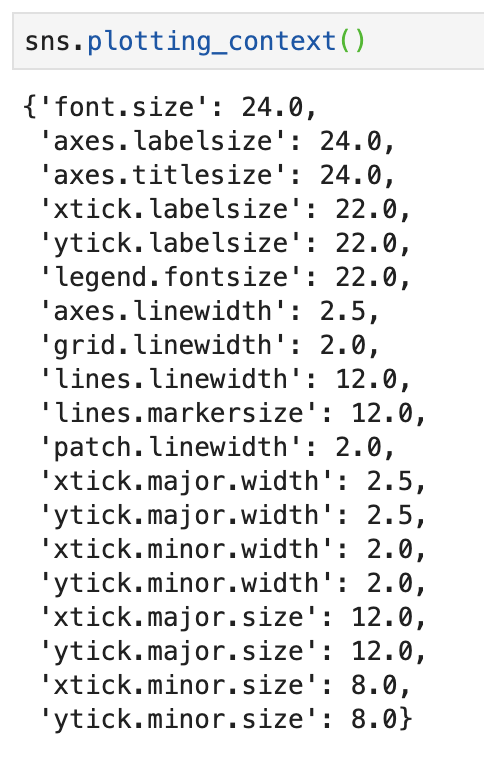

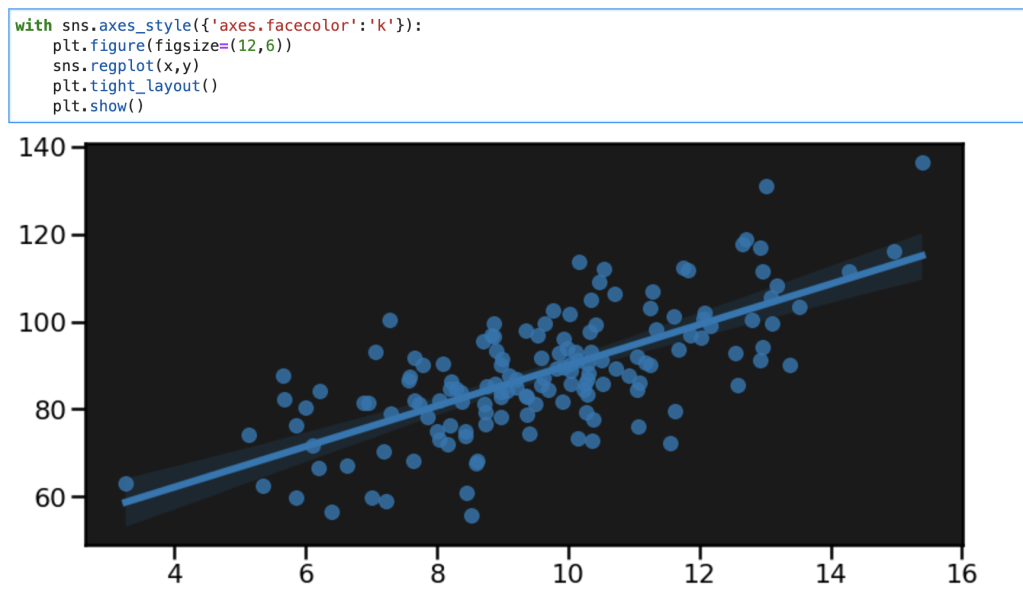

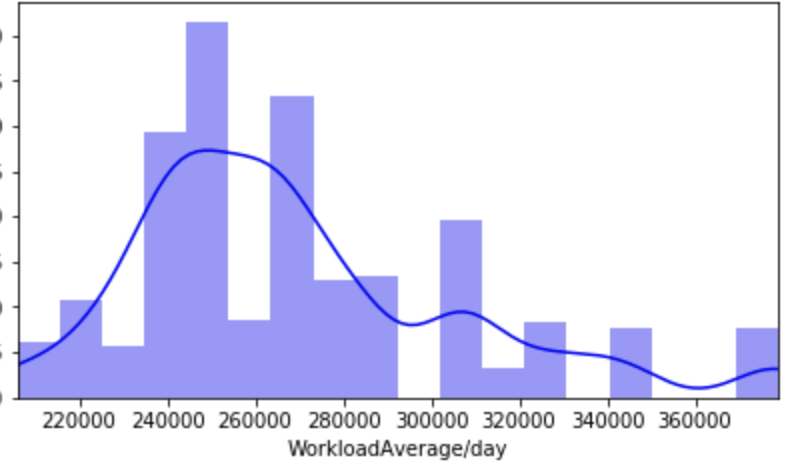

This section contains a sampling of all the exciting graphs to describe what Pokémon has looked like over the years.

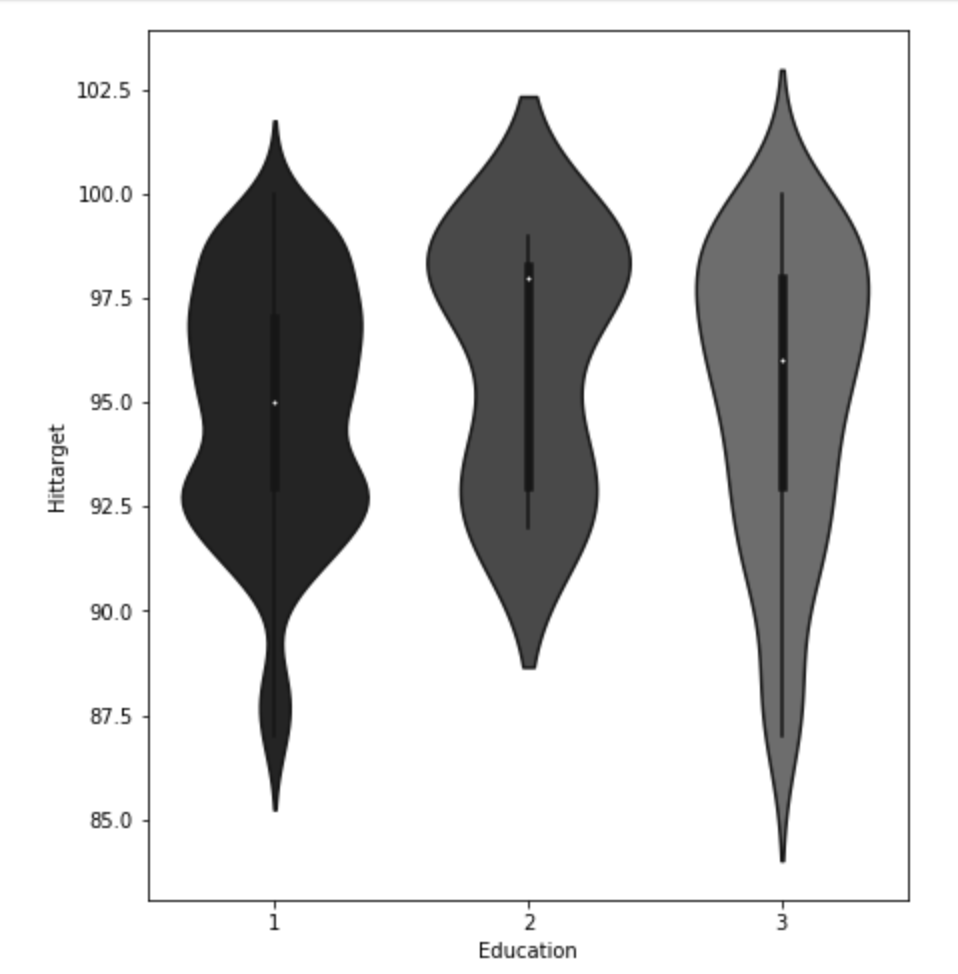

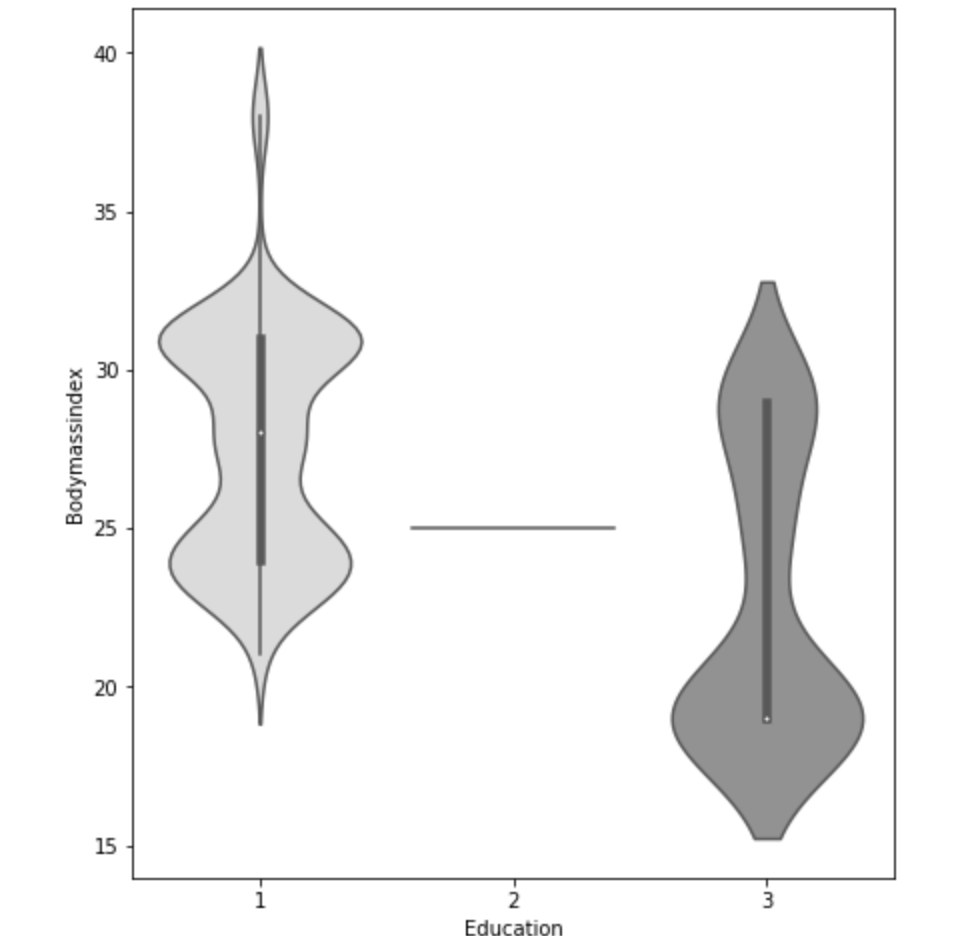

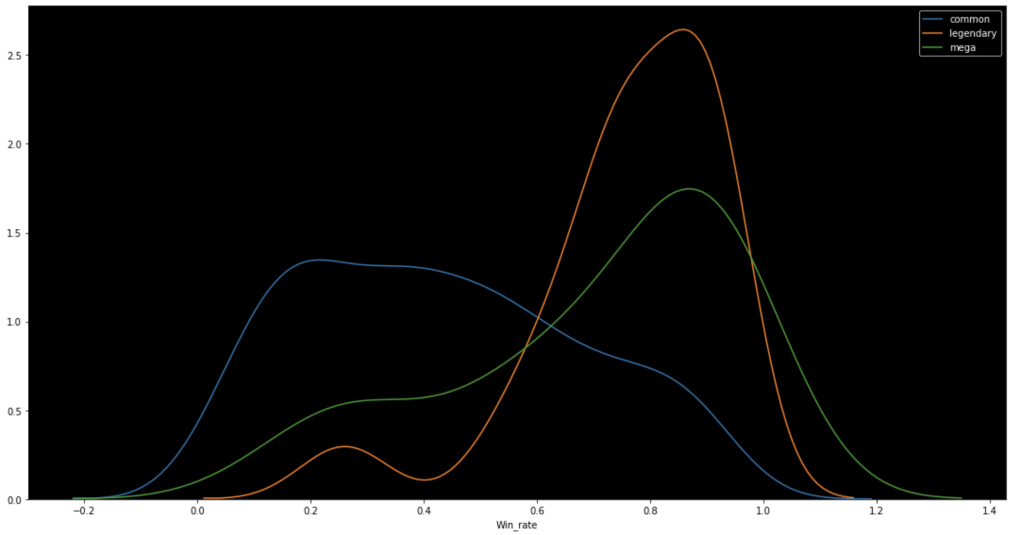

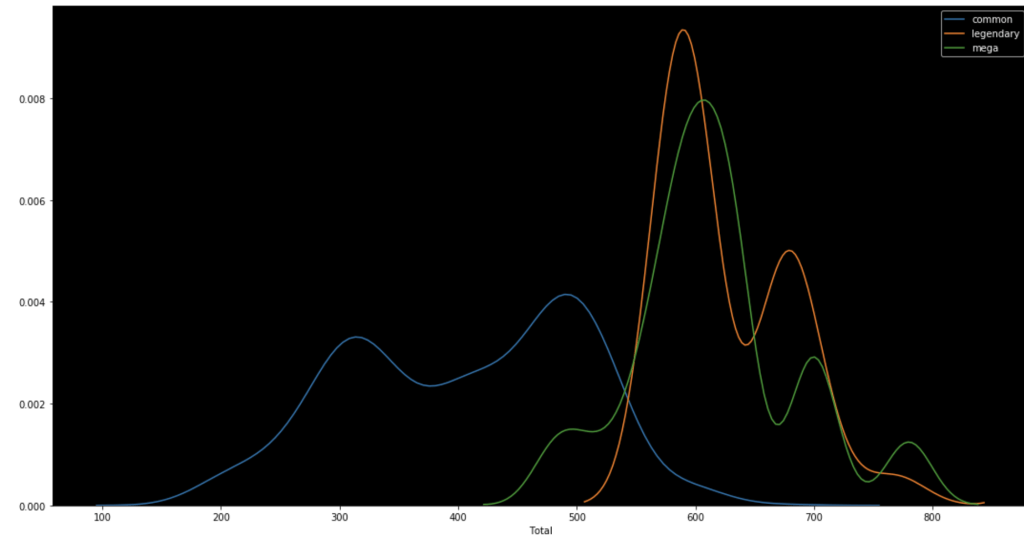

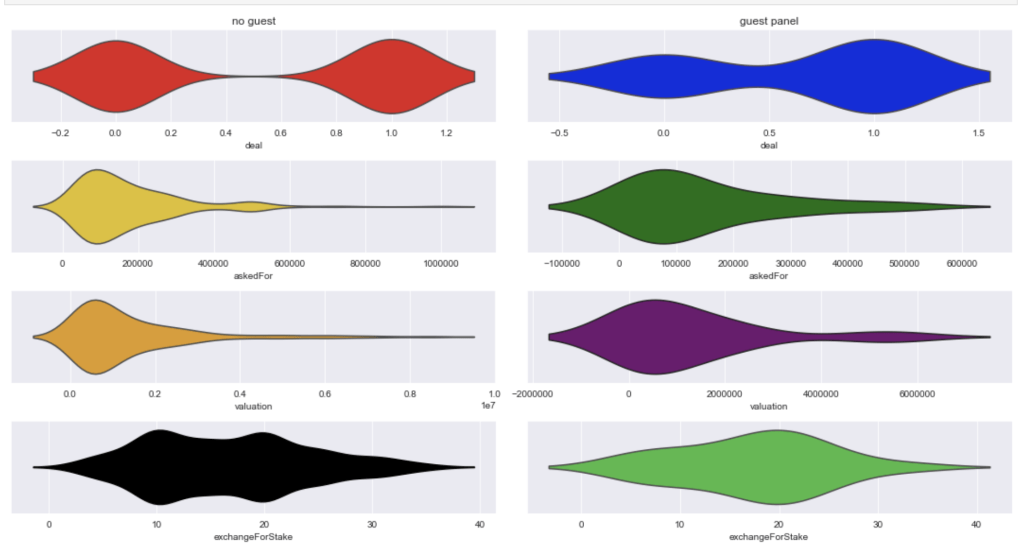

The following graph shows the distributions of win rate and total stats respectively segmented by Pokémon class.

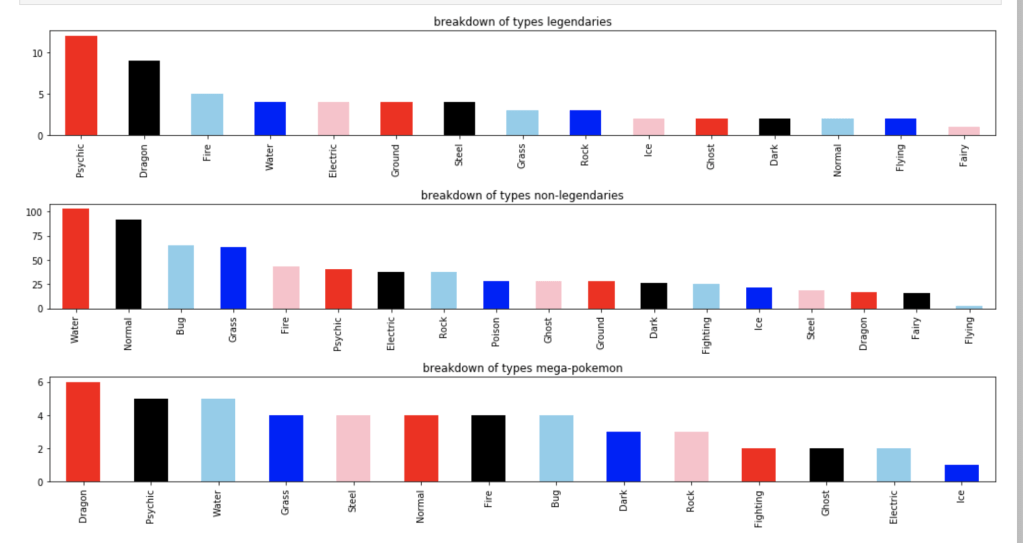

The following graph shows how many Pokémon appear for each type:

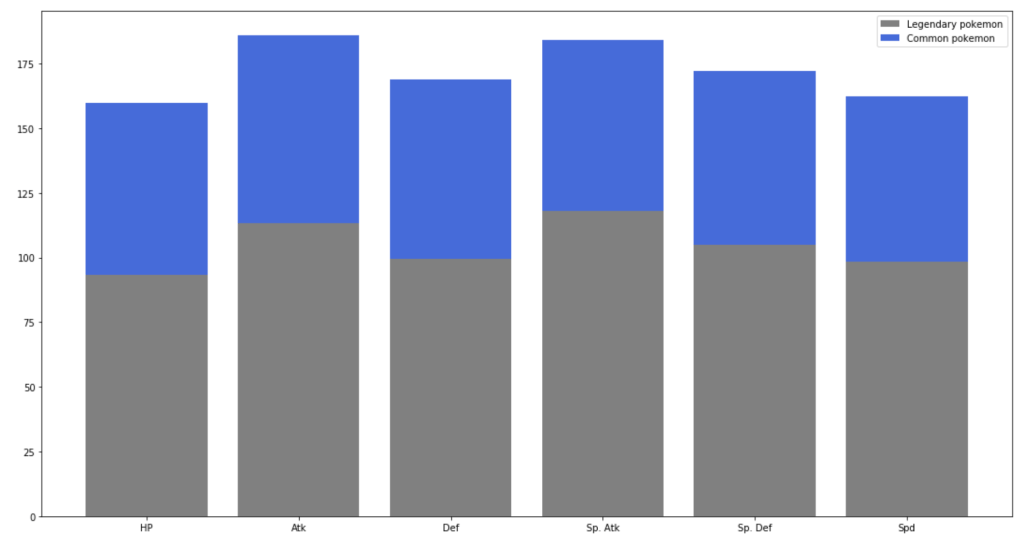

The graph below shows the difference between stats of legendary Pokémon and regular ones.

And next…

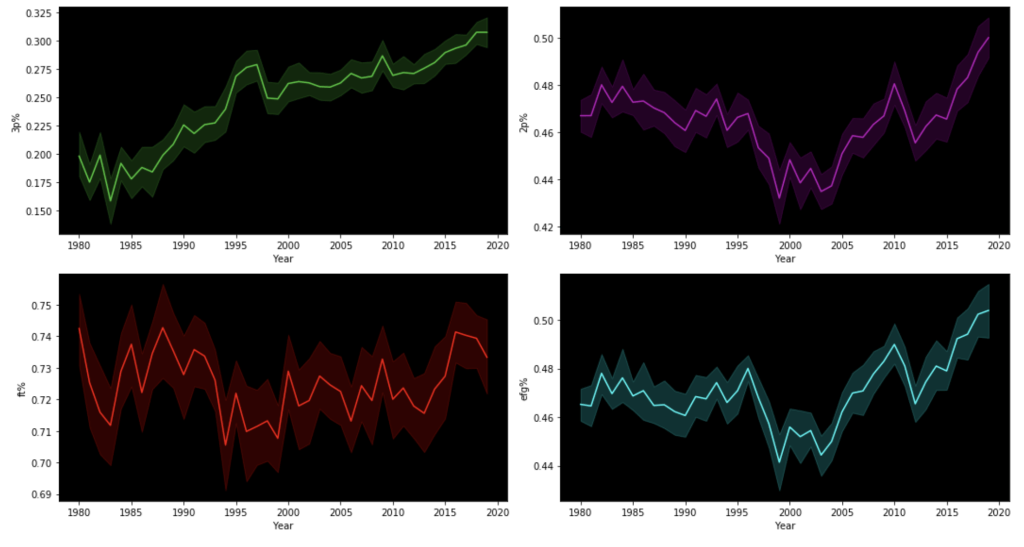

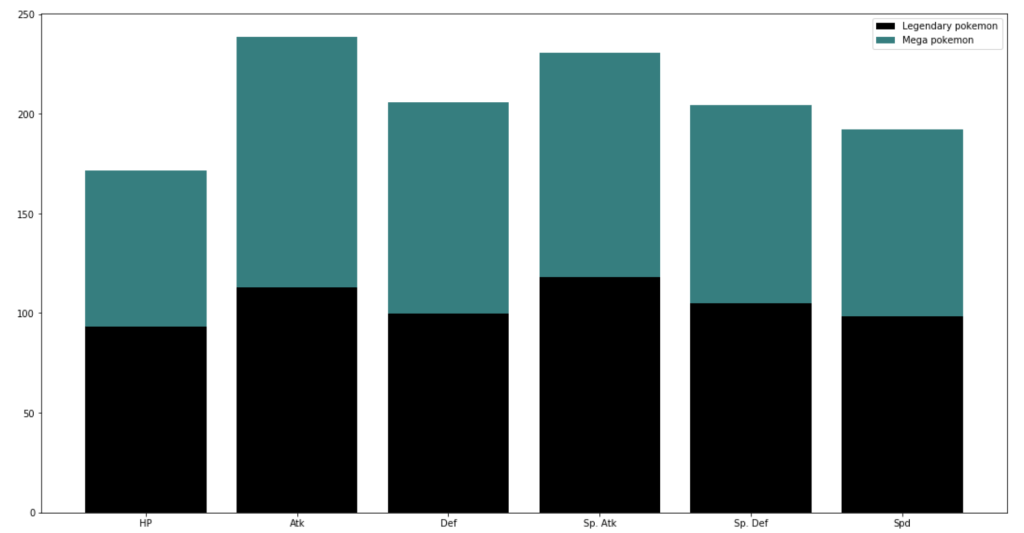

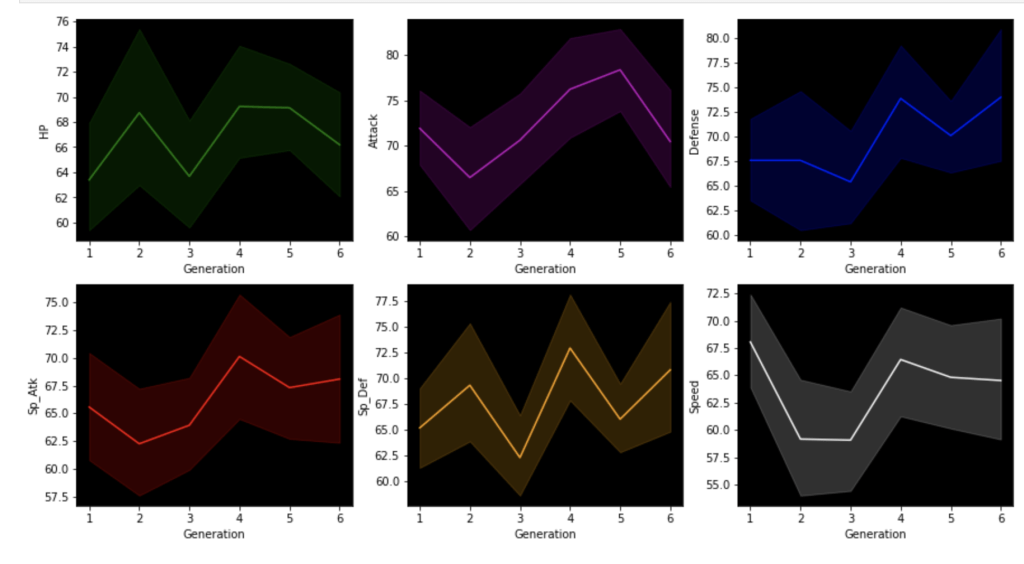

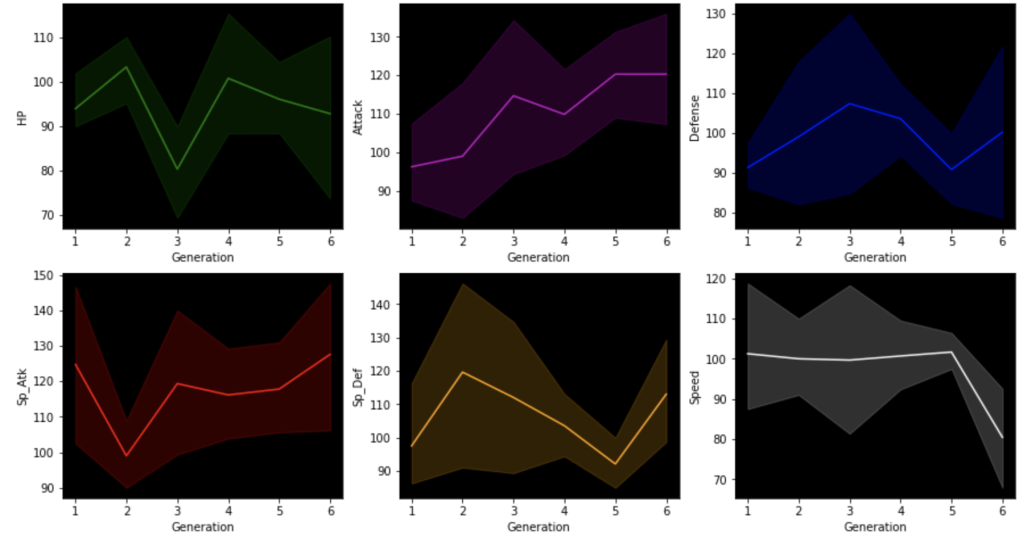

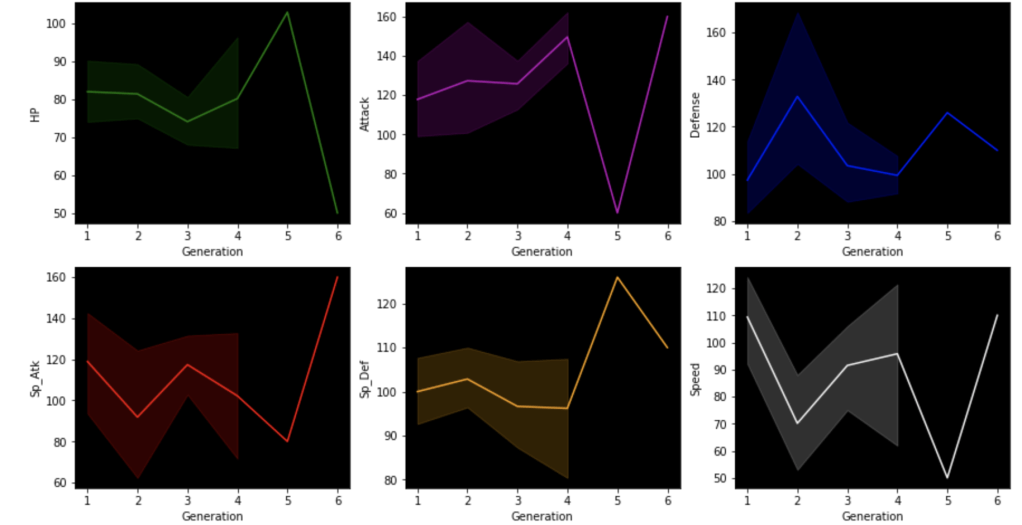

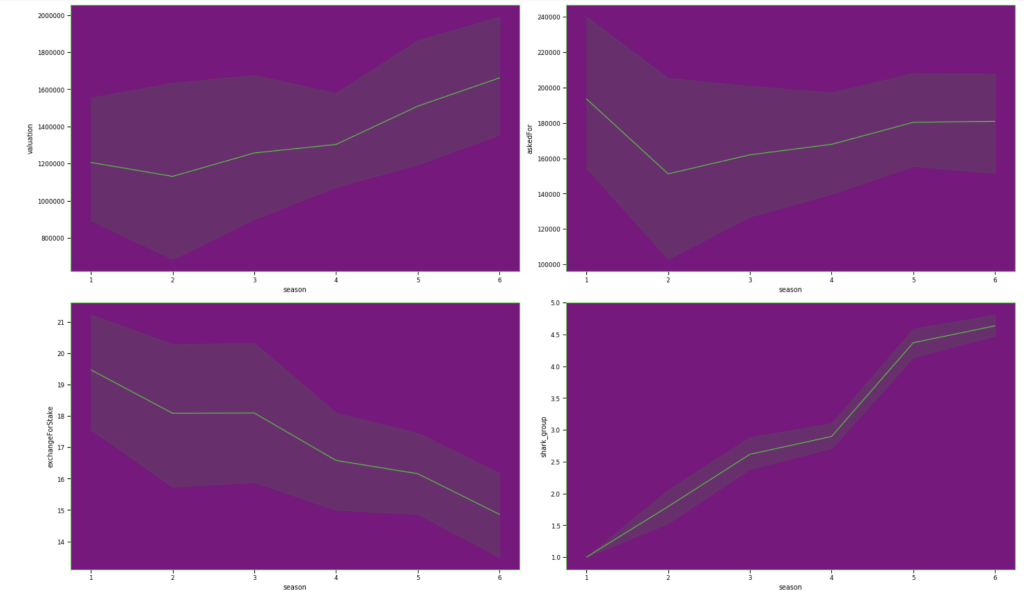

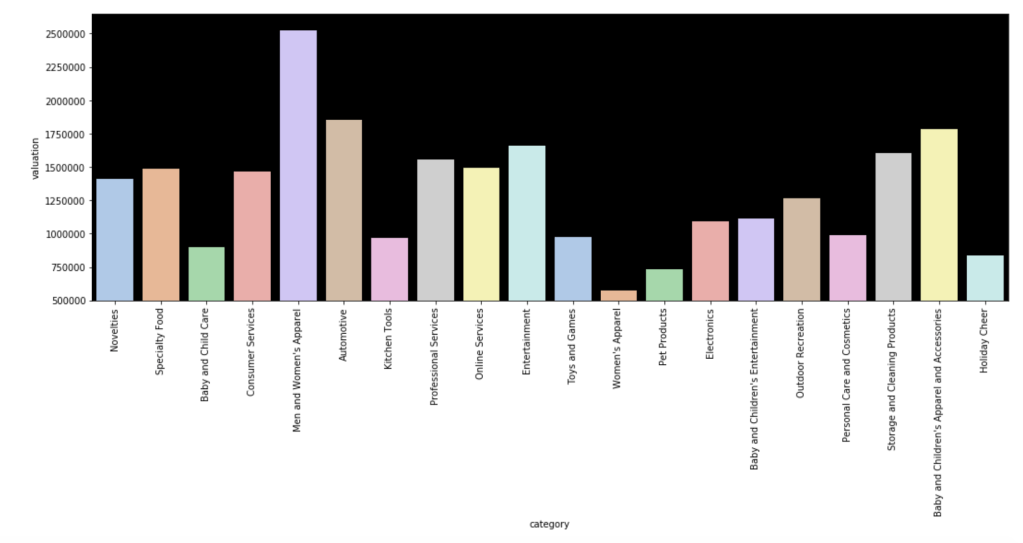

This next set of visuals show trends over the years in common, legendary, and mega Pokémon respectively.

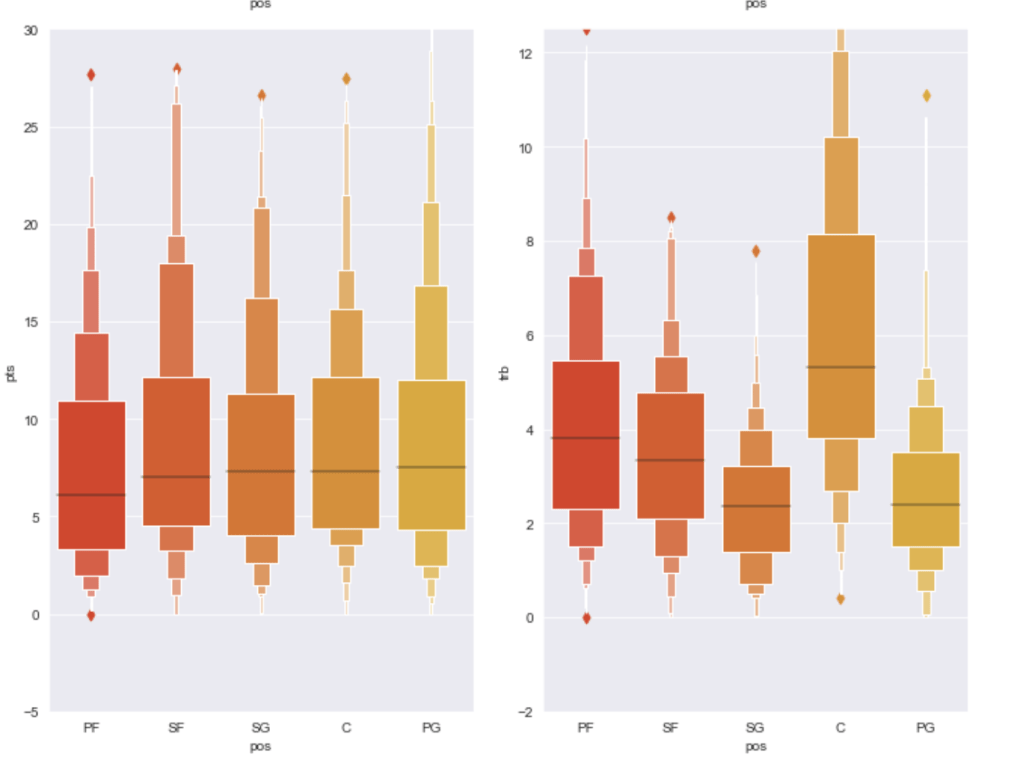

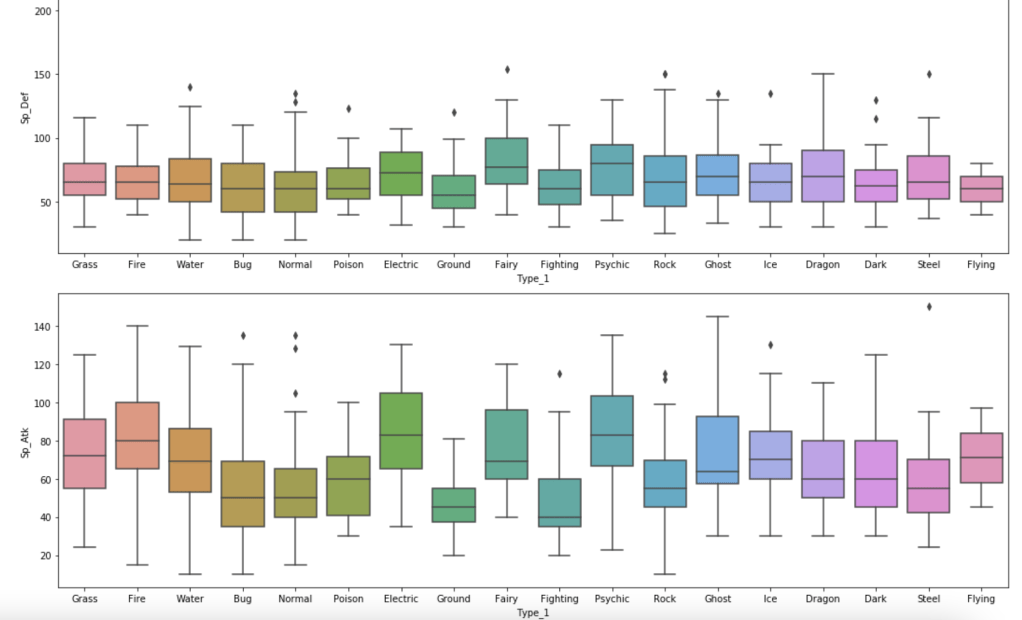

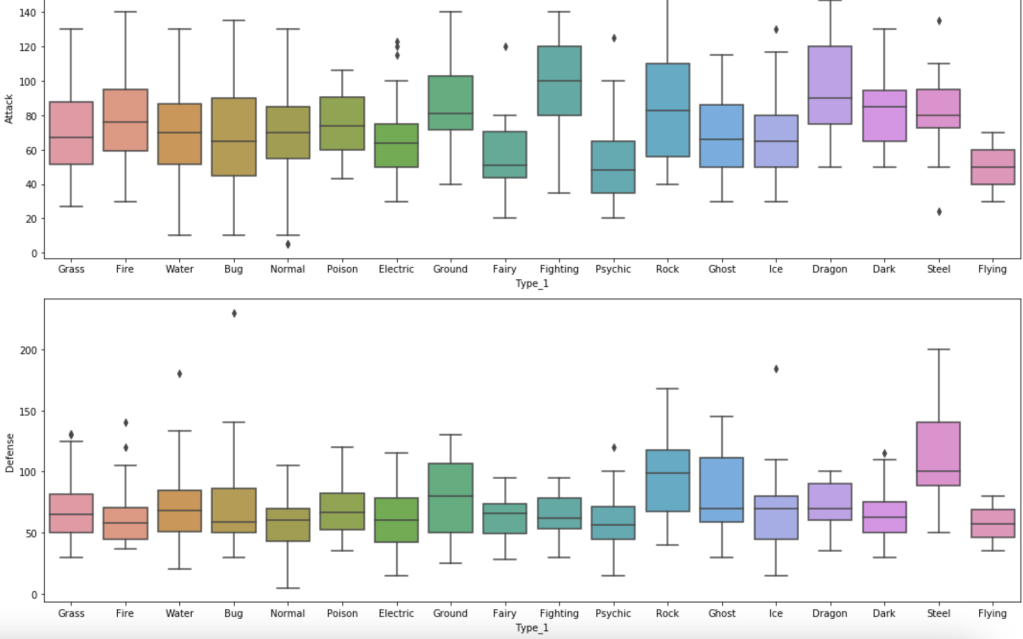

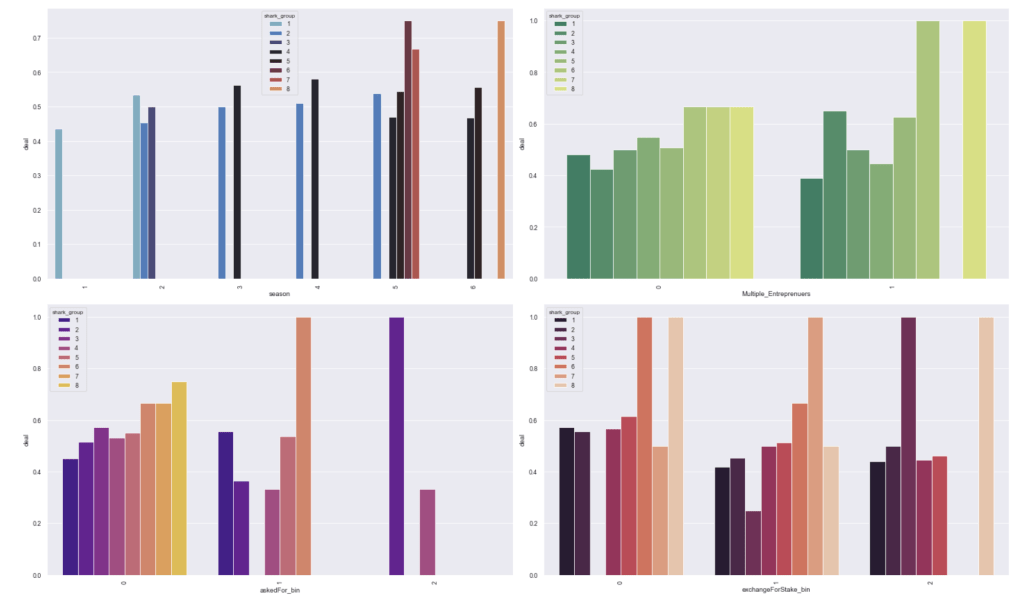

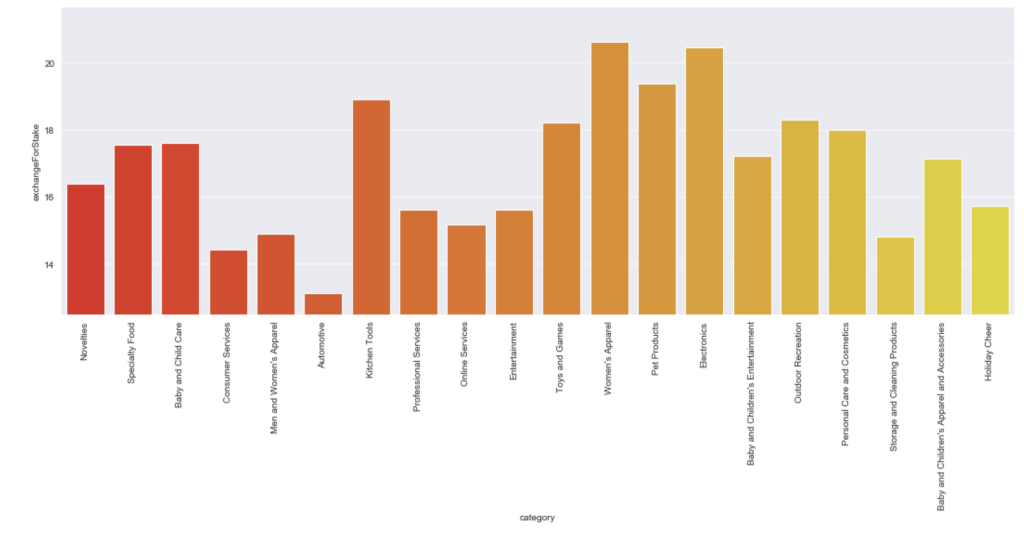

The next series of charts shows the distribution of stats by type with common Pokémon:

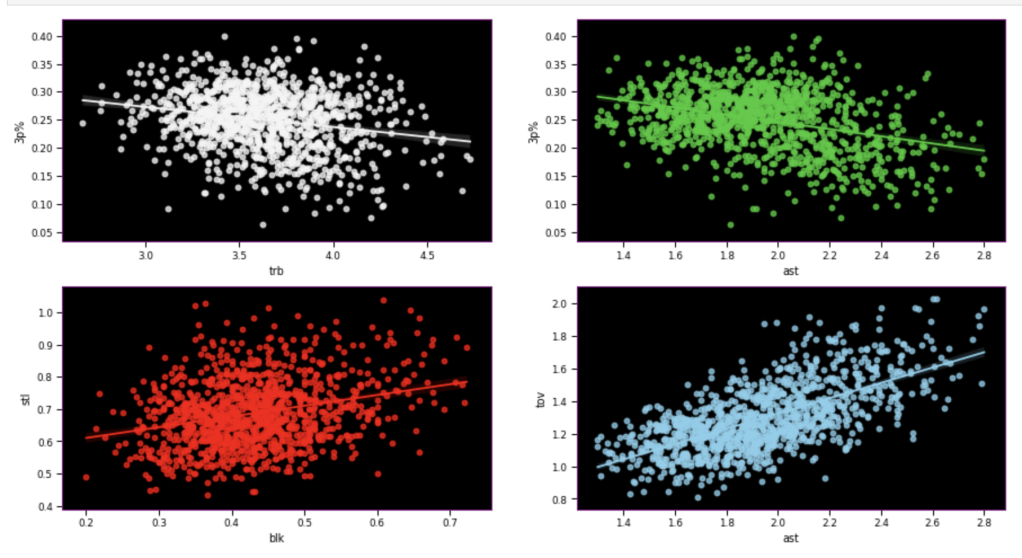

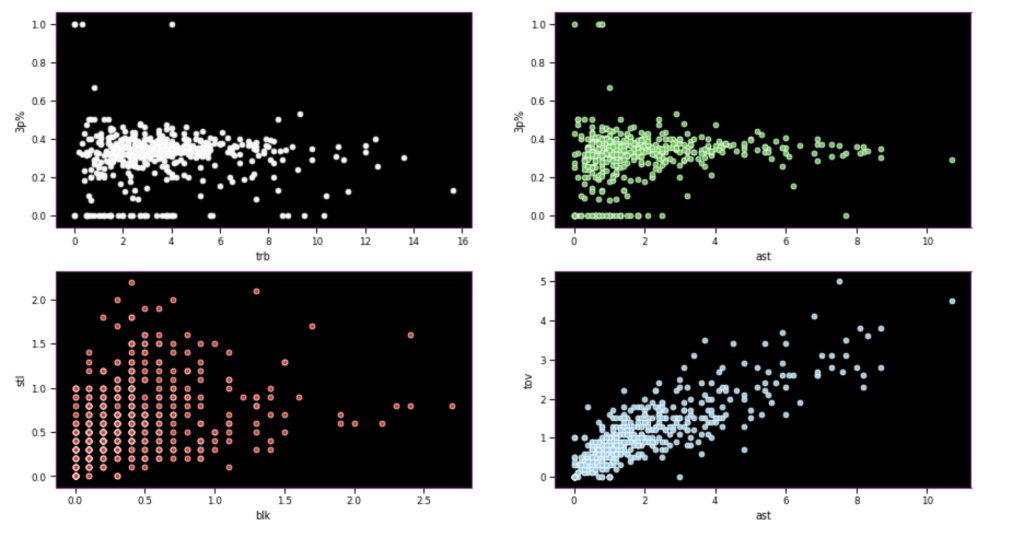

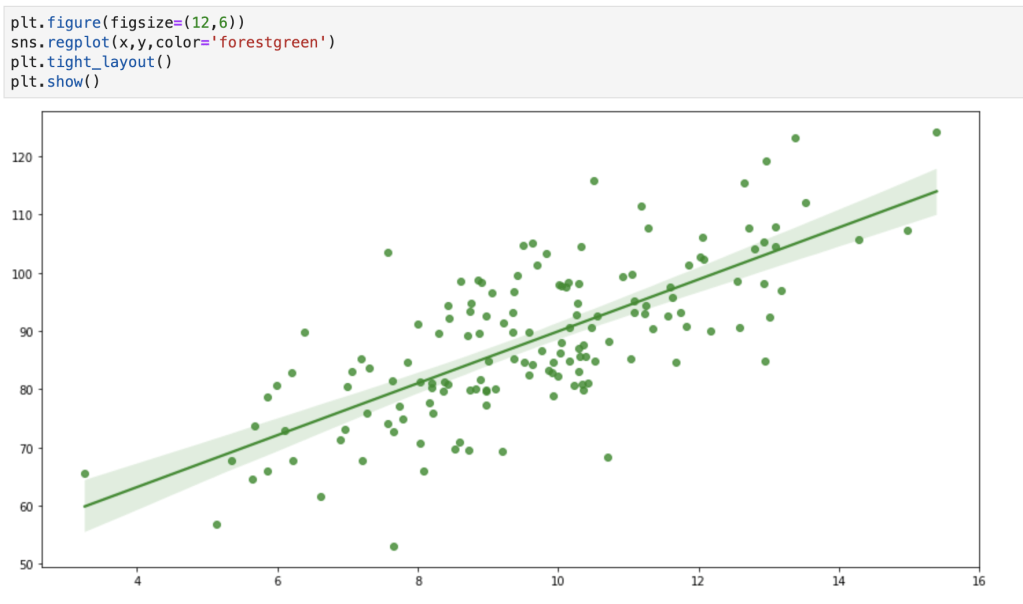

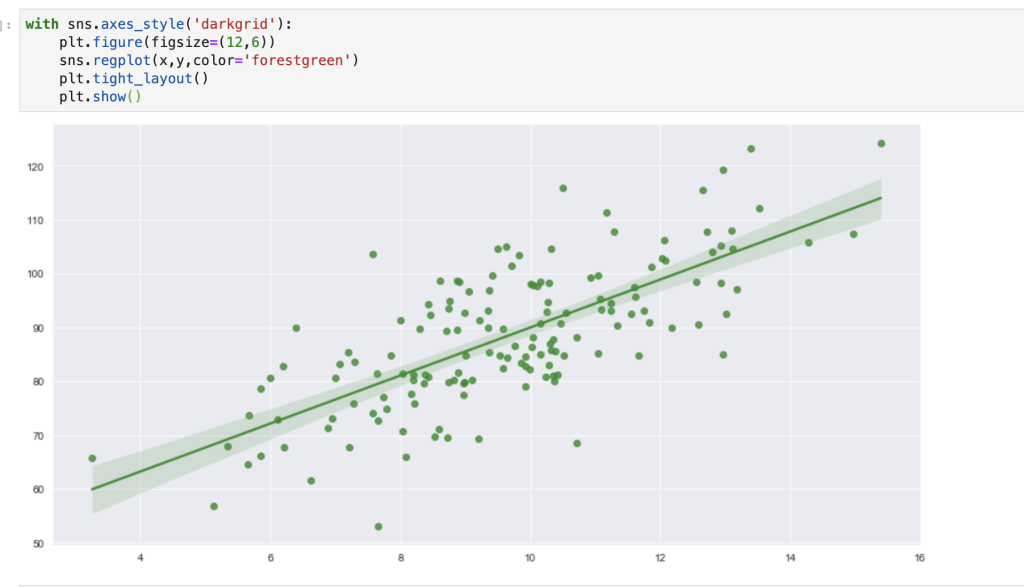

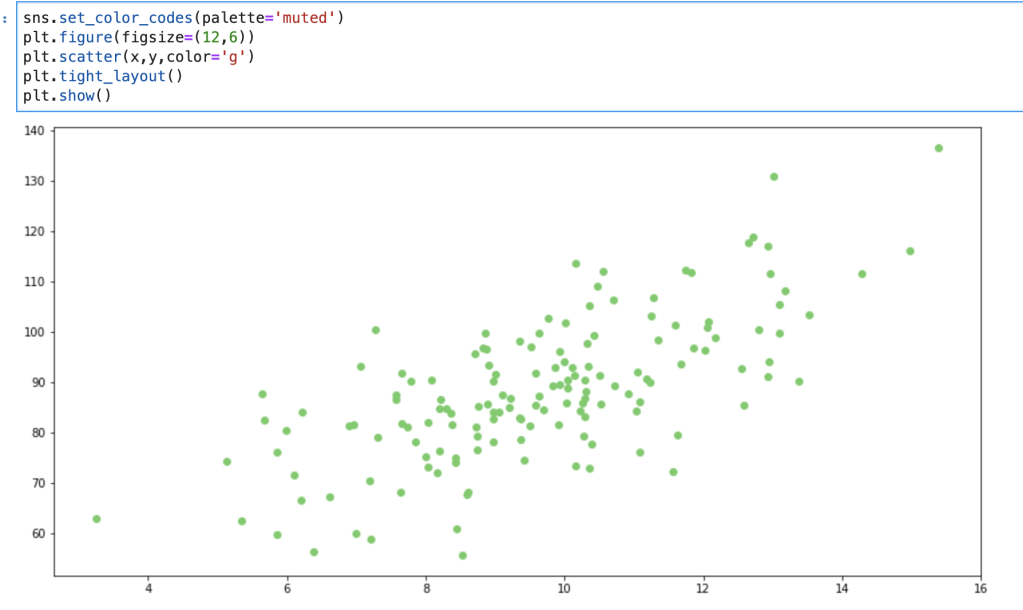

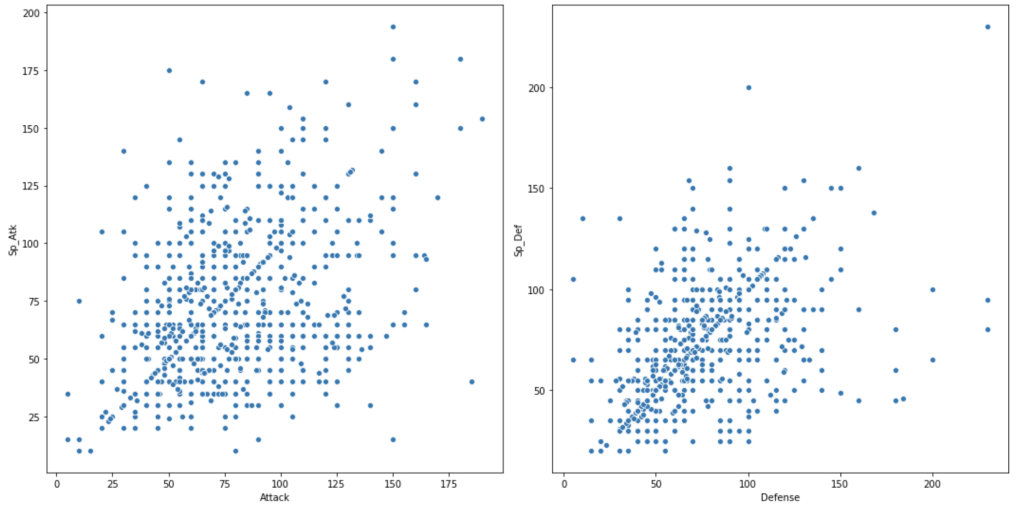

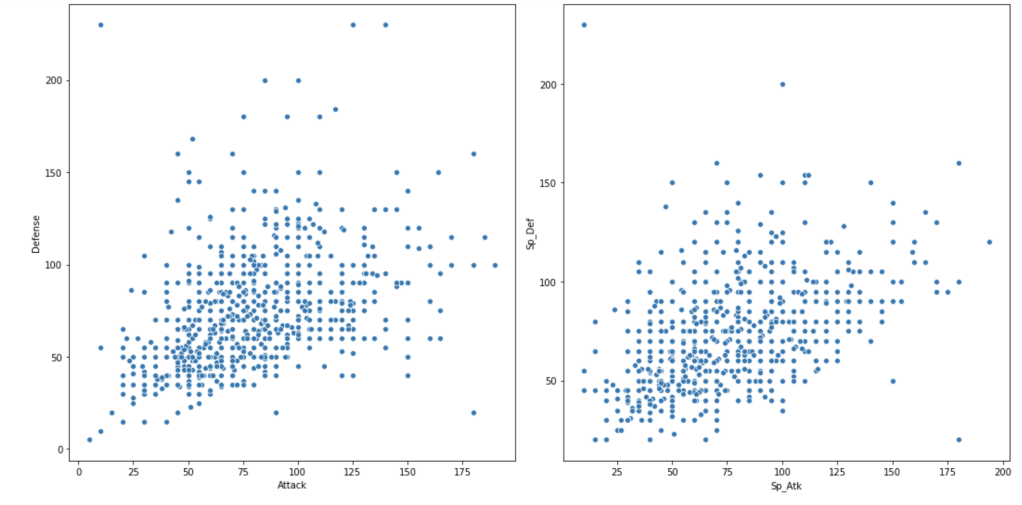

Next, we have scatter plots to compare attack and defense.

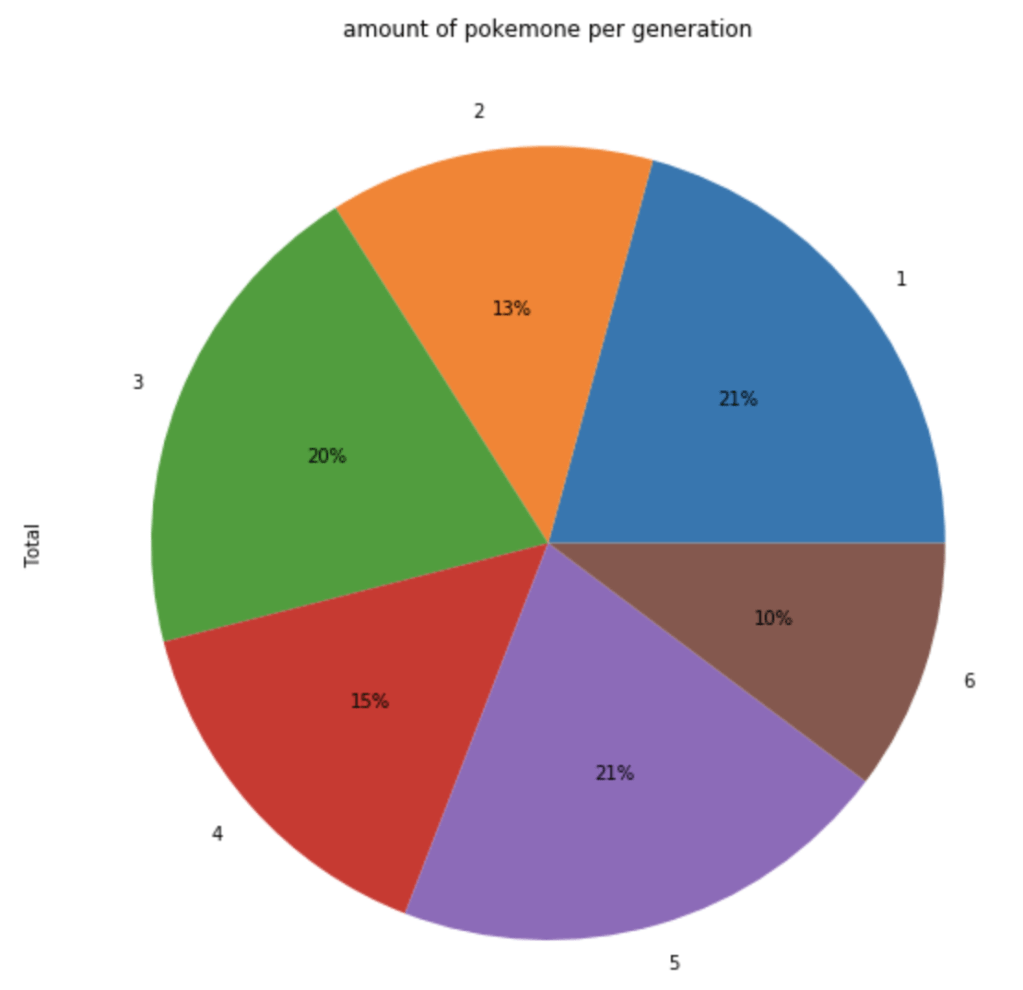

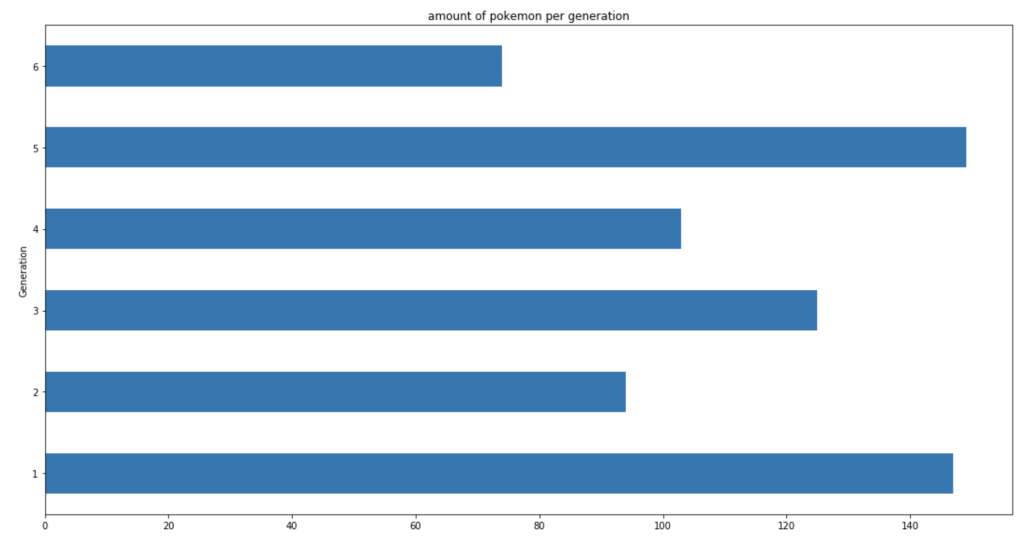

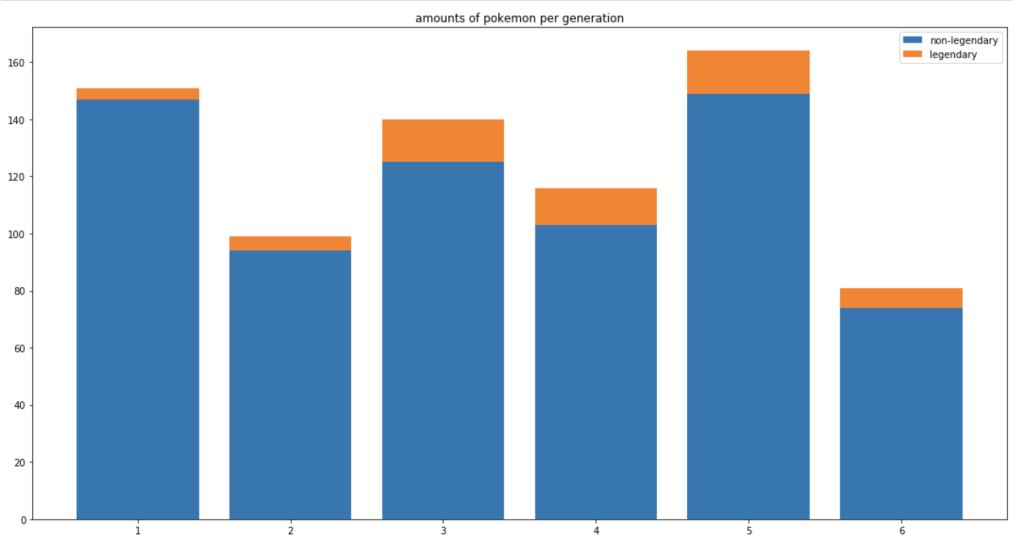

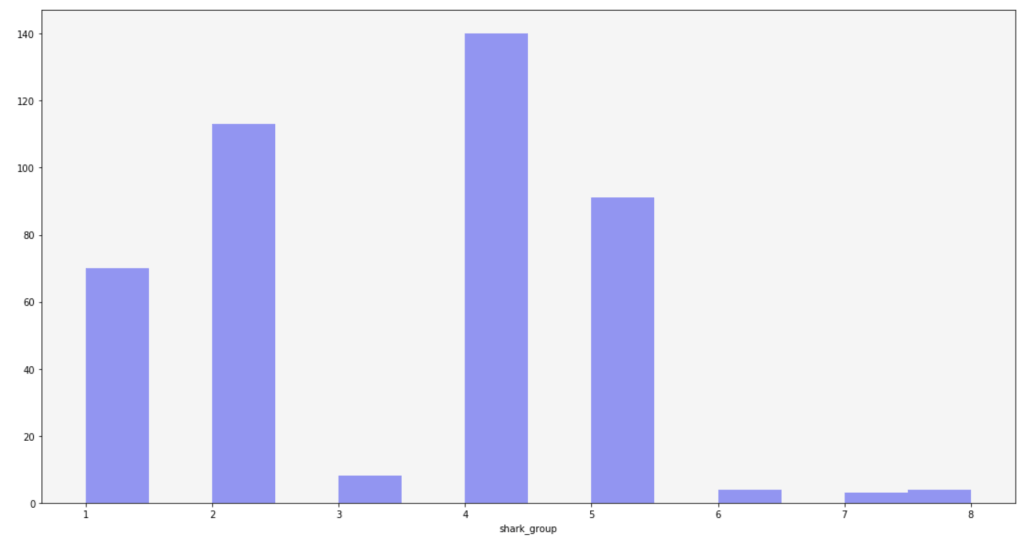

The next chart shows the distribution of total Pokémon across 6 generations.

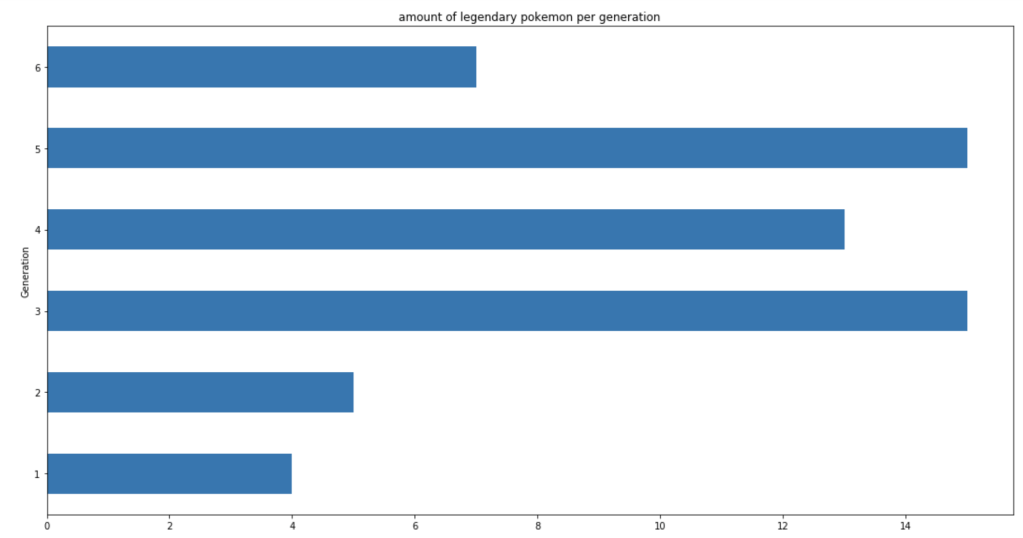

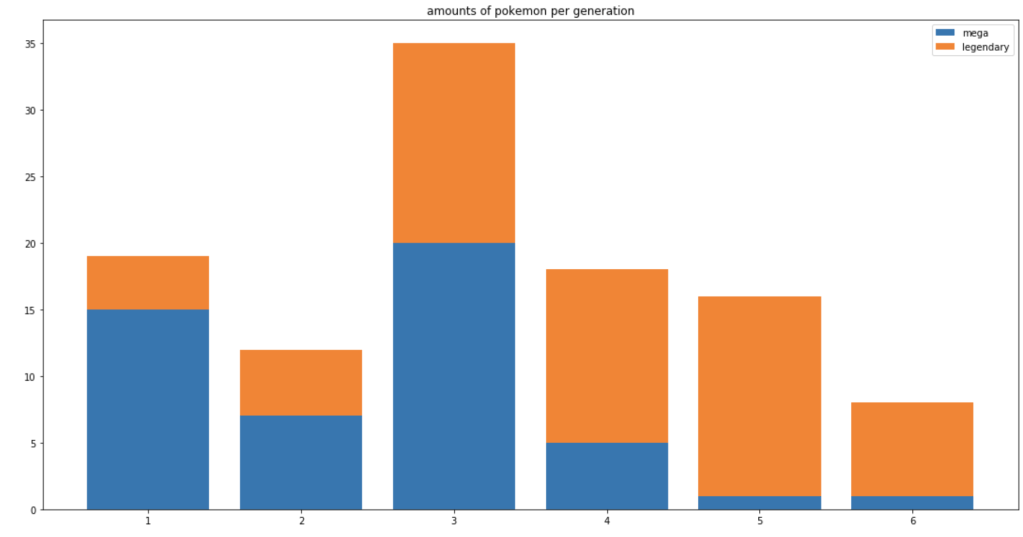

Let’s look at legendary and mega Pokémon.

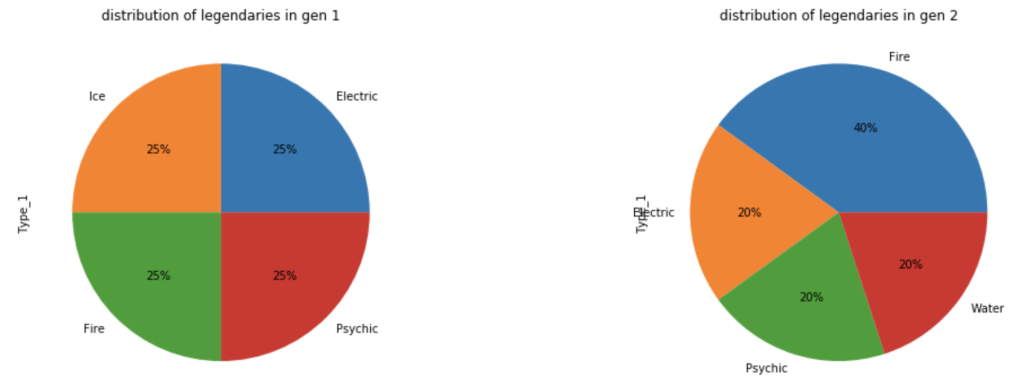

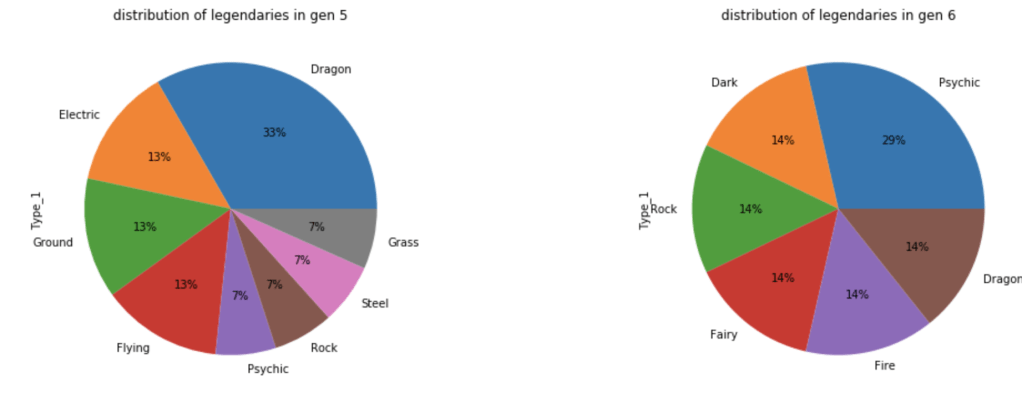

Let’s look at how these legendaries are distributed by type.

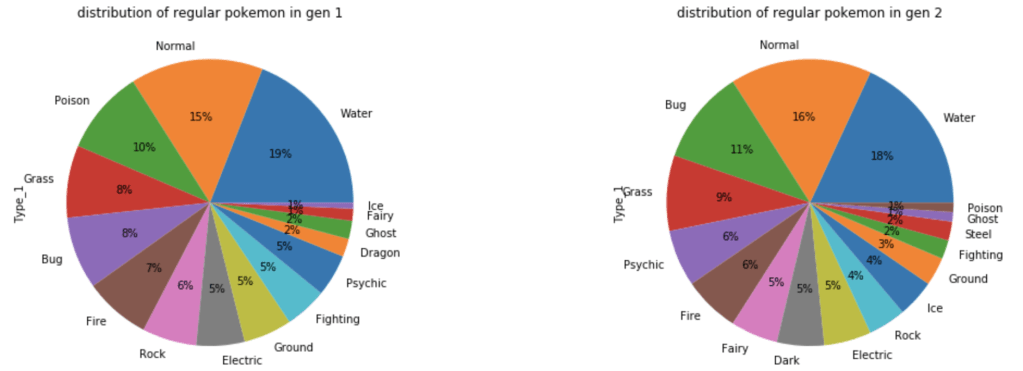

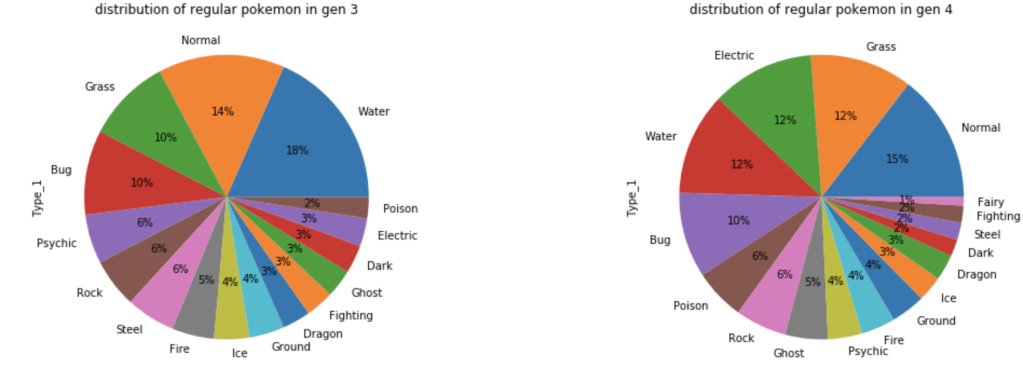

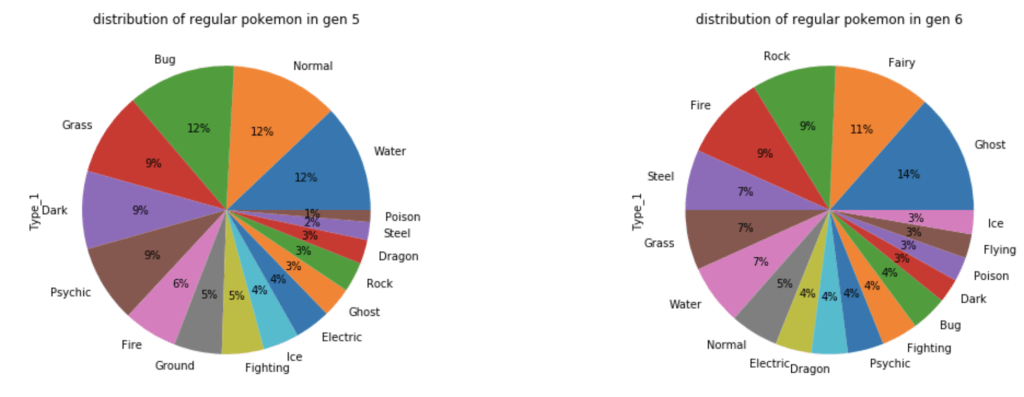

What about common Pokémon?

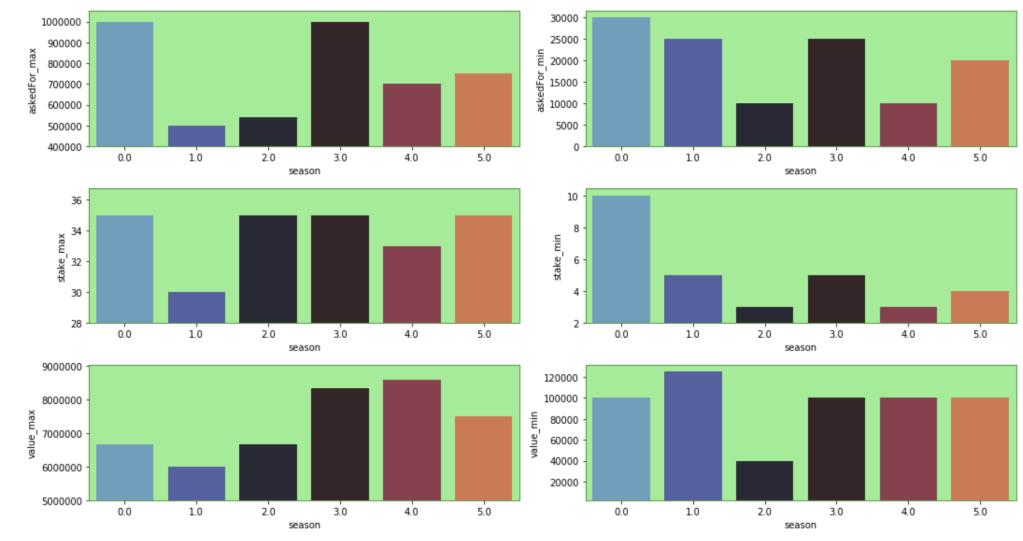

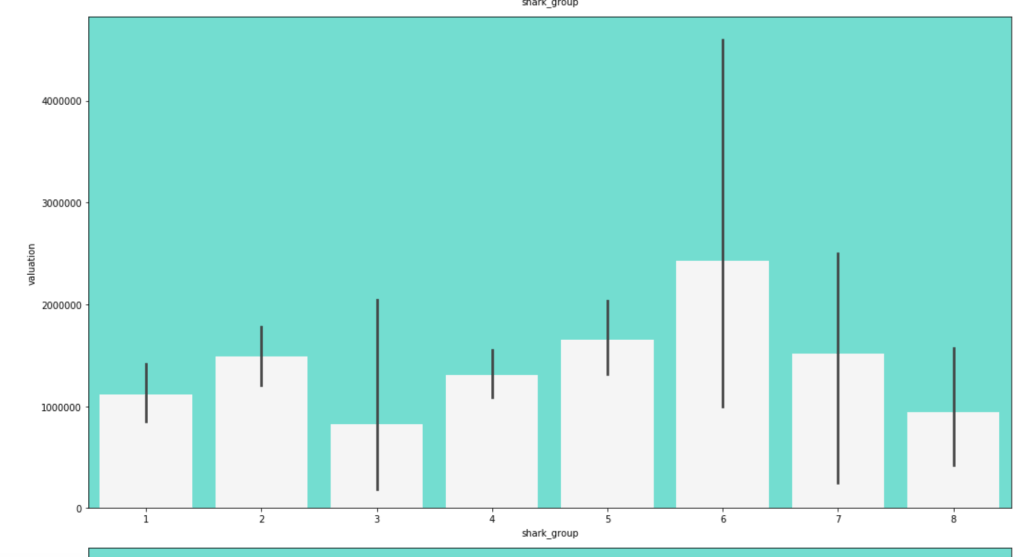

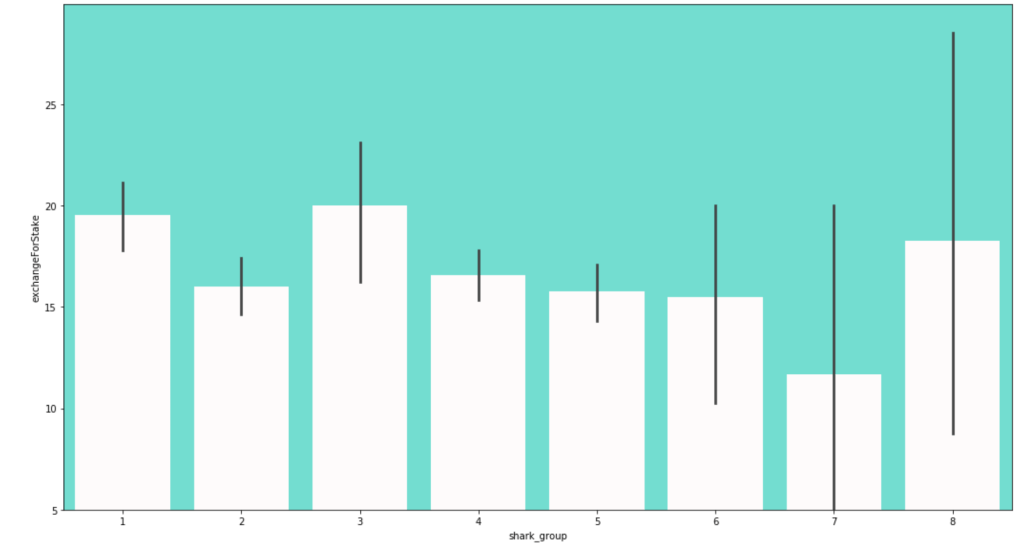

The next group of visuals shows distribution of stats by generation among legendary Pokémon.

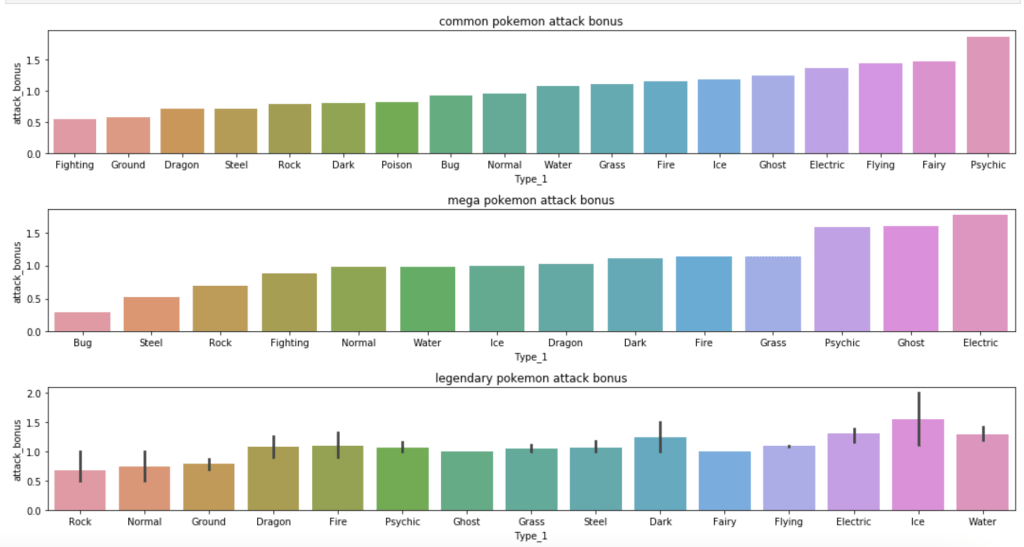

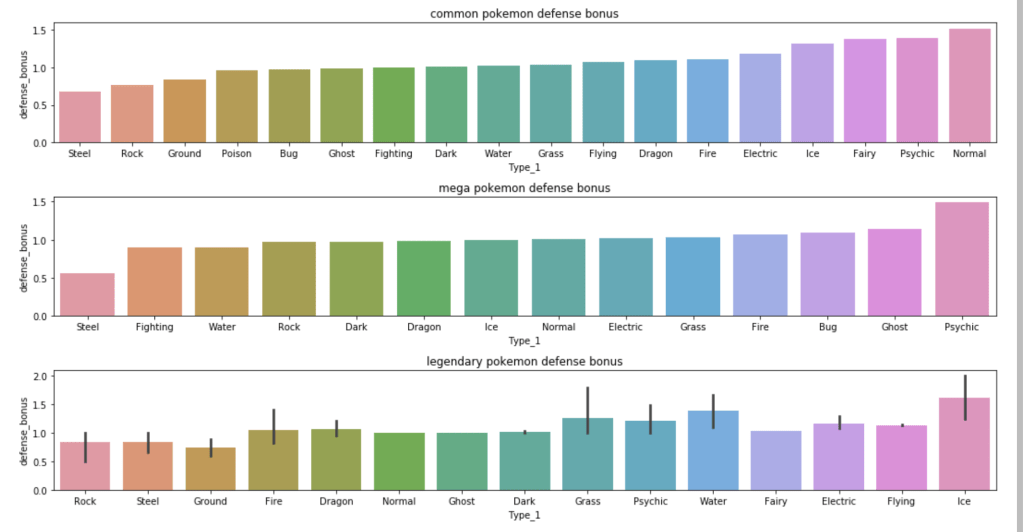

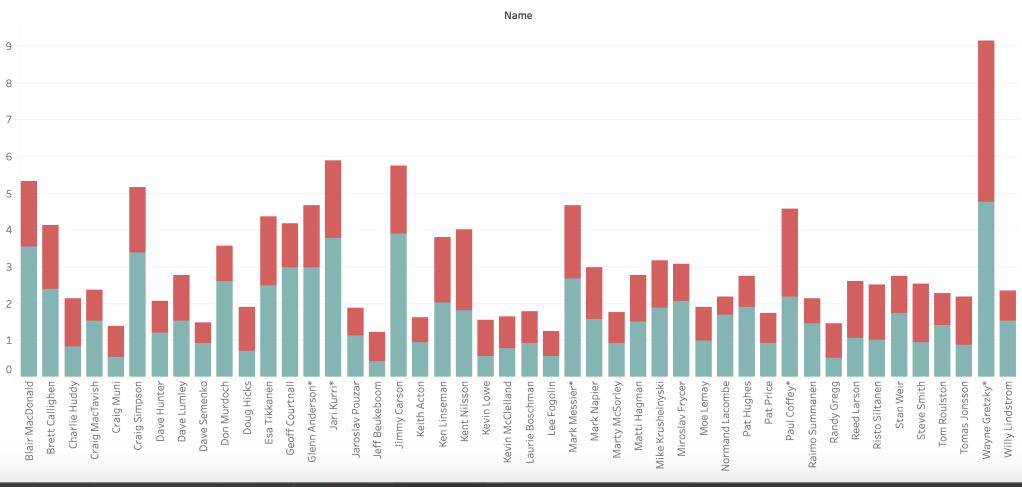

The next set of visuals shows which Pokémon have the highest ratio of special attack to attack

The next set of visuals shows which Pokémon have the highest ratio of special defense to defense

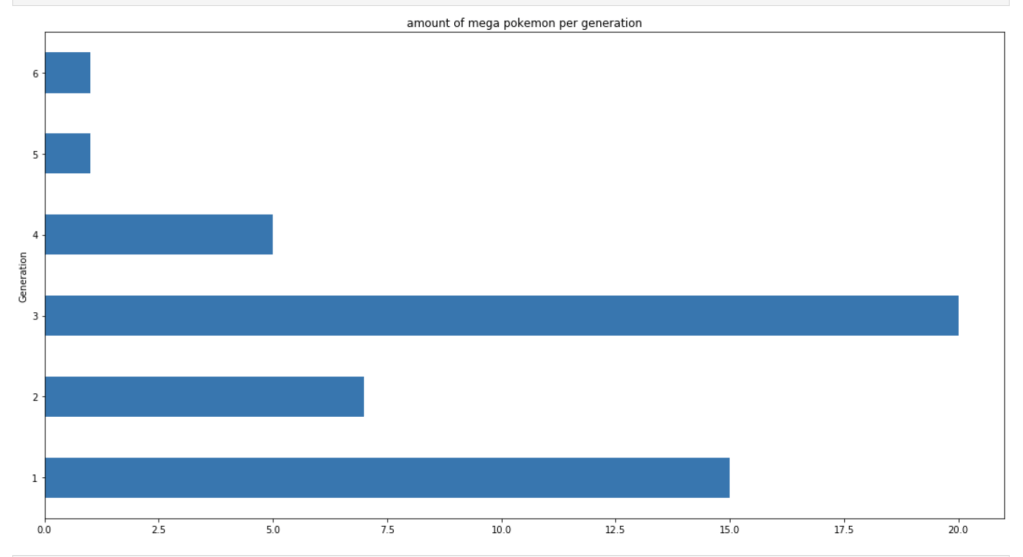

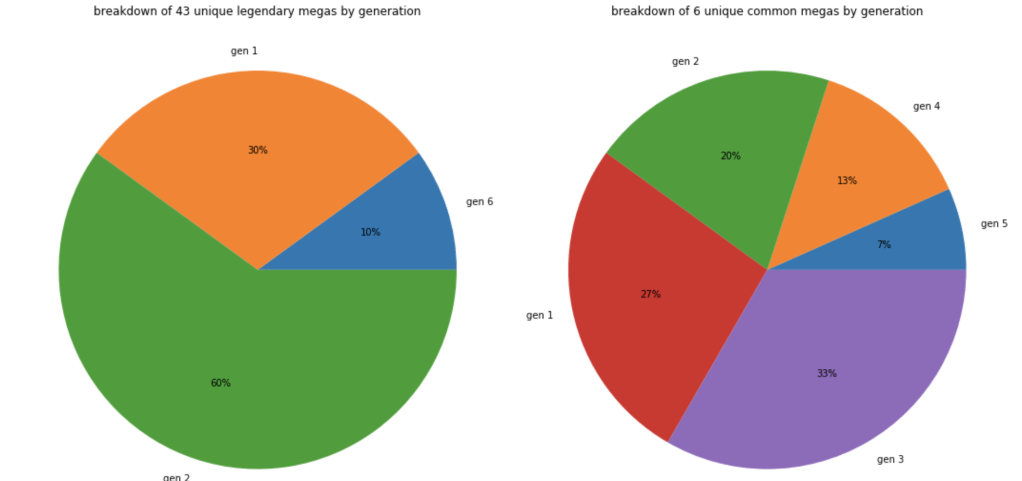

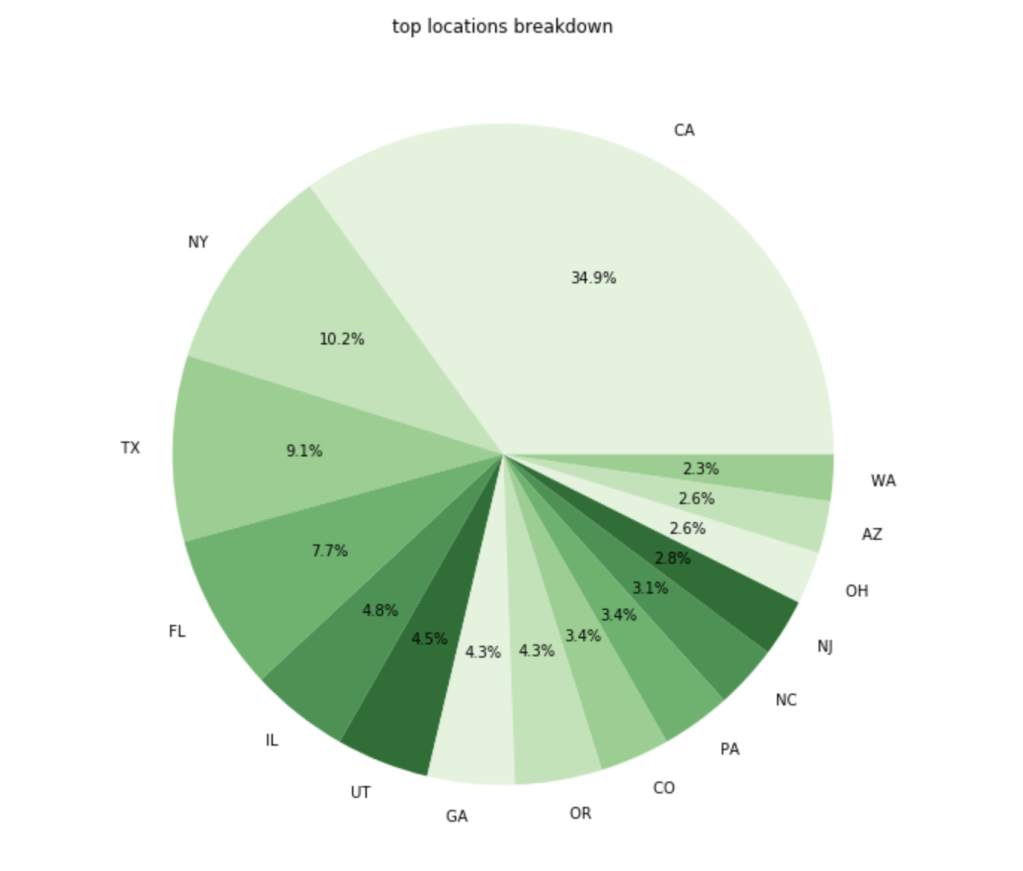

This next set of charts show where mega Pokémon come from.

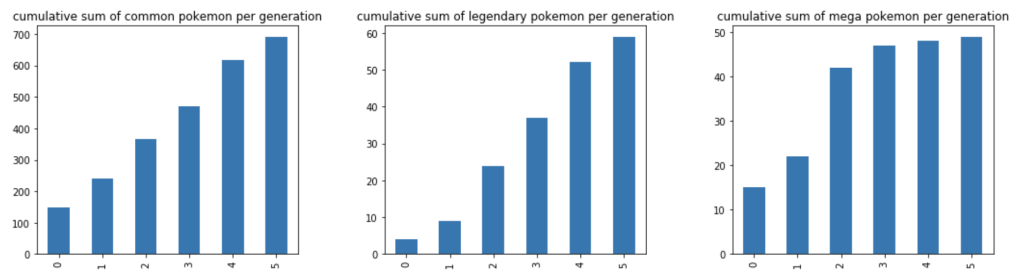

Next, we have a cumulative rise in total Pokémon over the generations.

Models

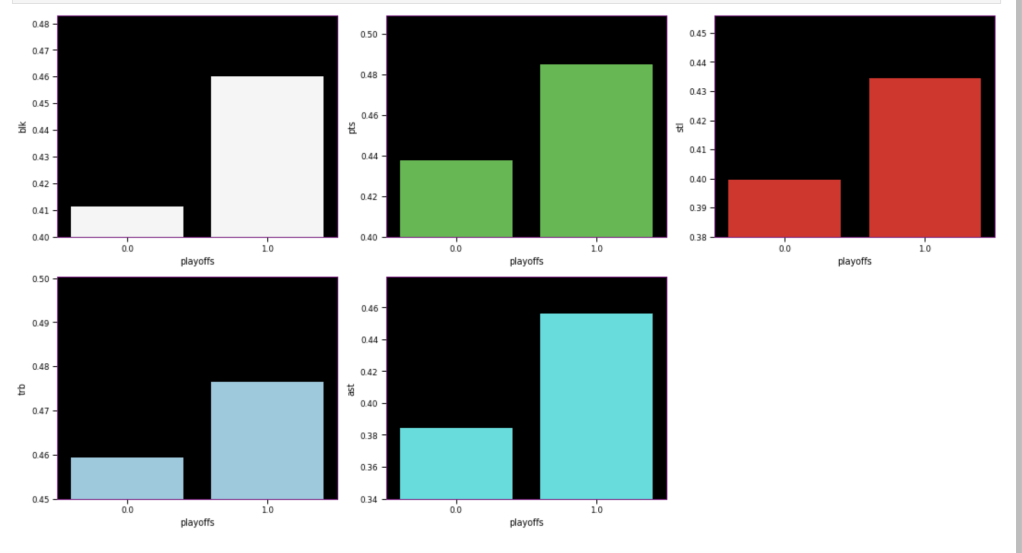

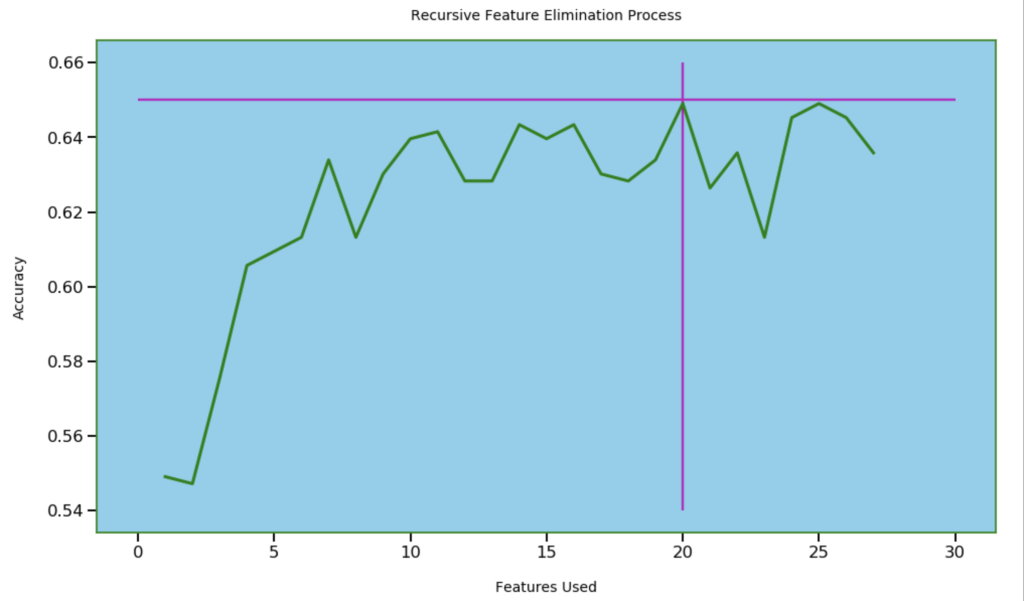

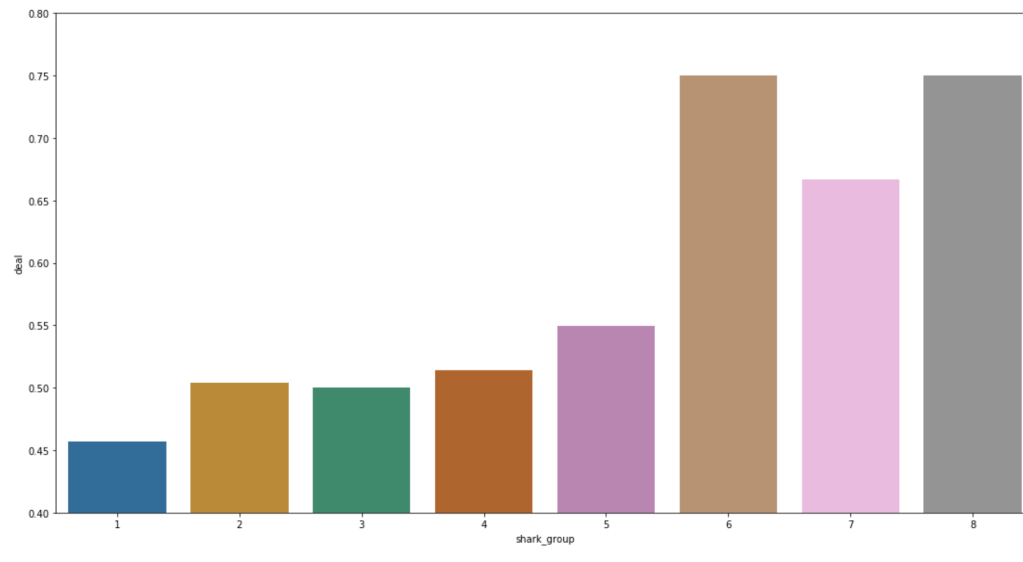

As I mentioned above, I ran continuous models and discrete models. I ran models for 3 classes of Pokémon: common, legendary, and mega. I also tried various groupings of input features to find the best model while not having any single model dominated by one feature completely. We’ll soon see that some features have outsized impacts.

Continuous Models

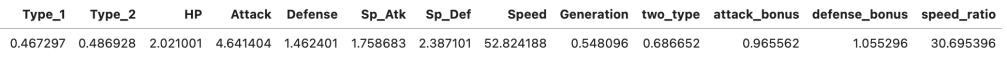

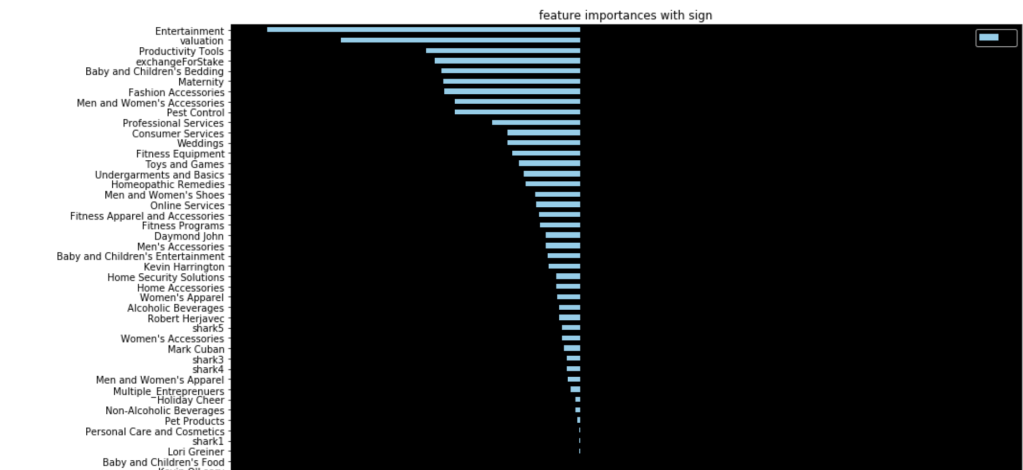

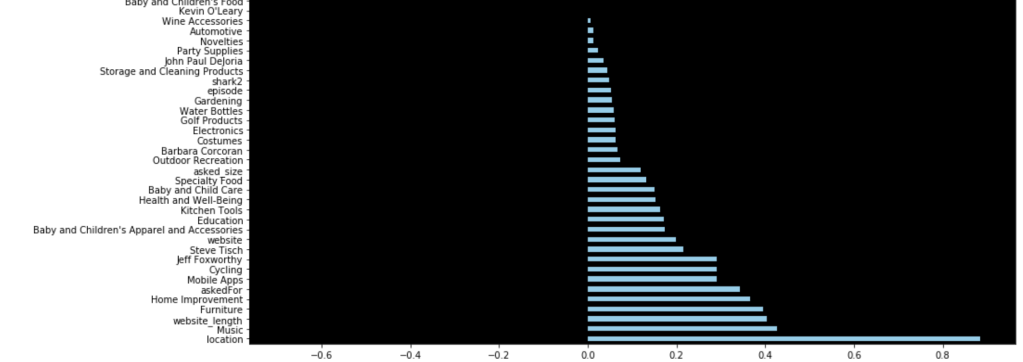

The first and most basic model yielded the following feature importance while having 90% accuracy:

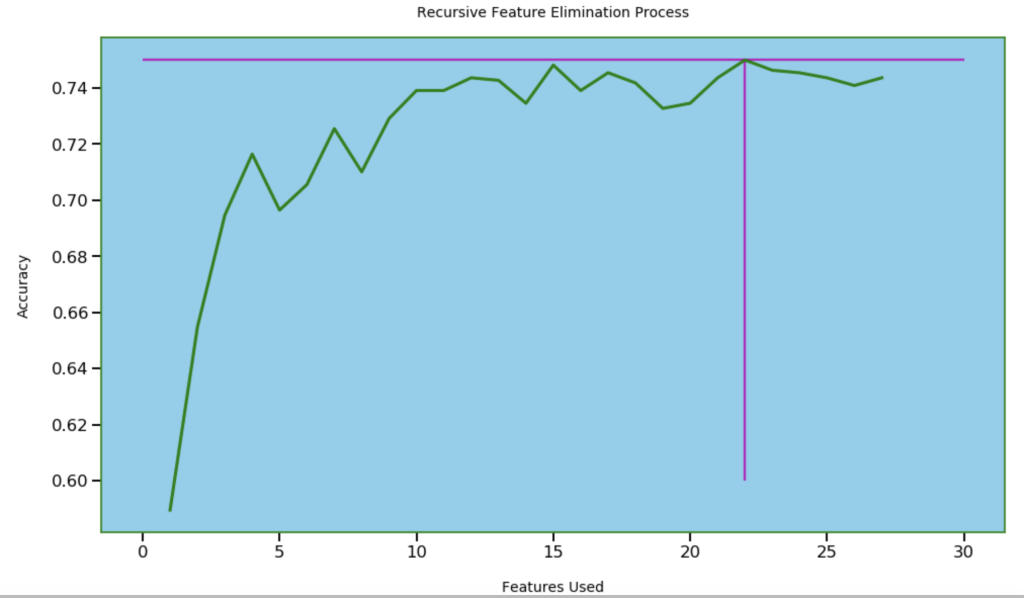

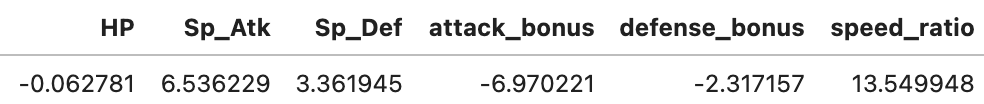

Speed and speed ratio were too powerful, so after removing them my accuracy dropped 26% (you read that right). This means I need speed or speed ratio. I chose to keep speed ratio. Also, I removed the type 1, type 2, generation, and “two-type” features based on p-values. Now, I had 77% accuracy with the following feature ranks.

I’ll skip some steps here, but the following feature importances, along with 75% accuracy, seemed most satisfactory:

Interestingly, having special attack/defense being higher than regular attack/defense is not good. I suppose you want a Pokémon’s special stats to be in line with regular ones.

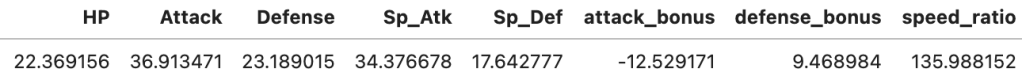

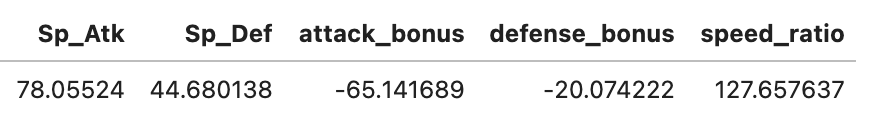

I’ll skip some steps again, but here are my results for mega and legendaries within the continuous model:

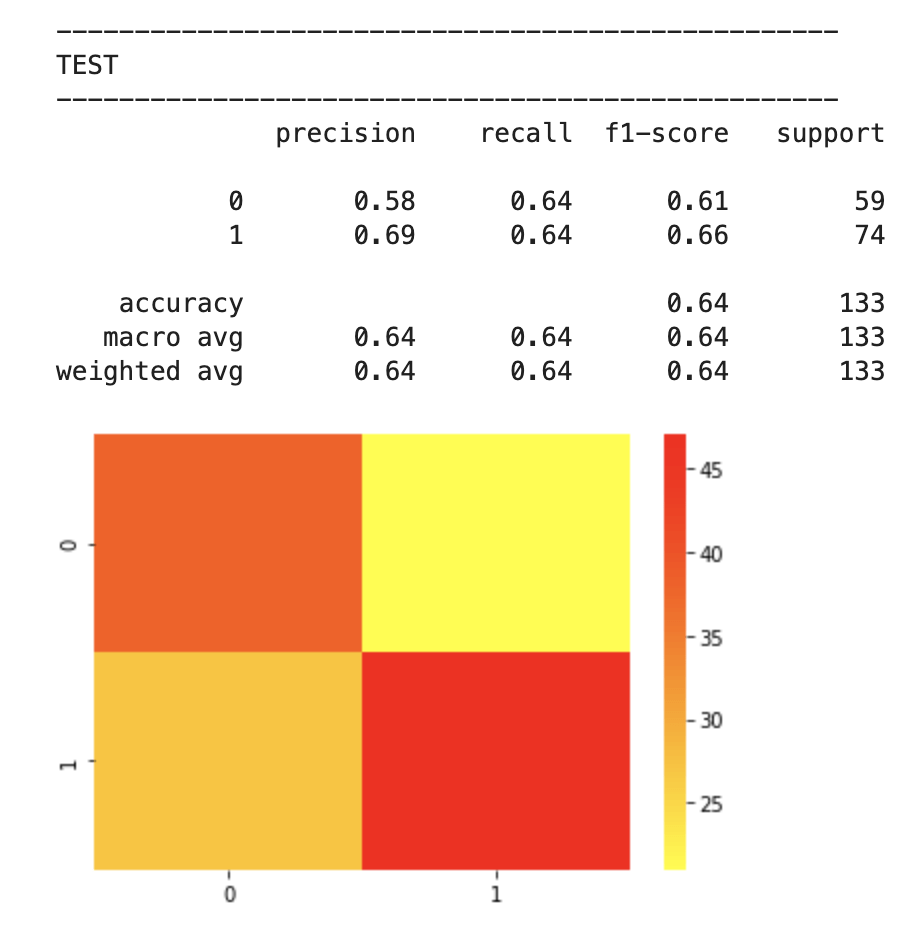

Legendary with 60% accuracy:

Mega with 91% accuracy:

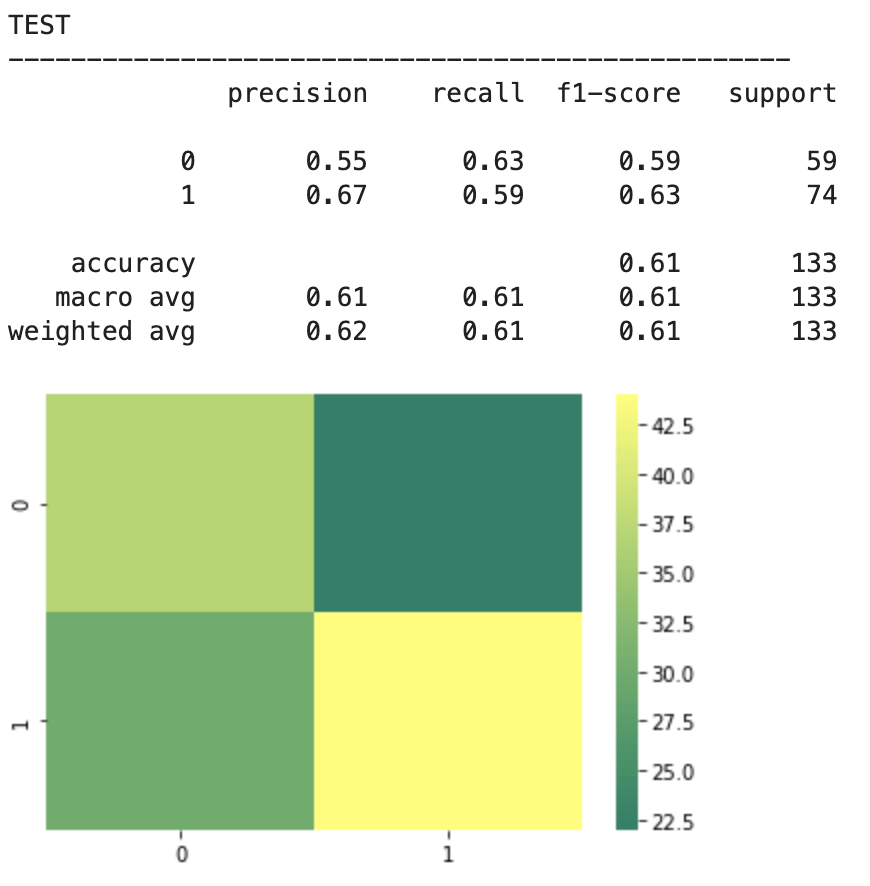

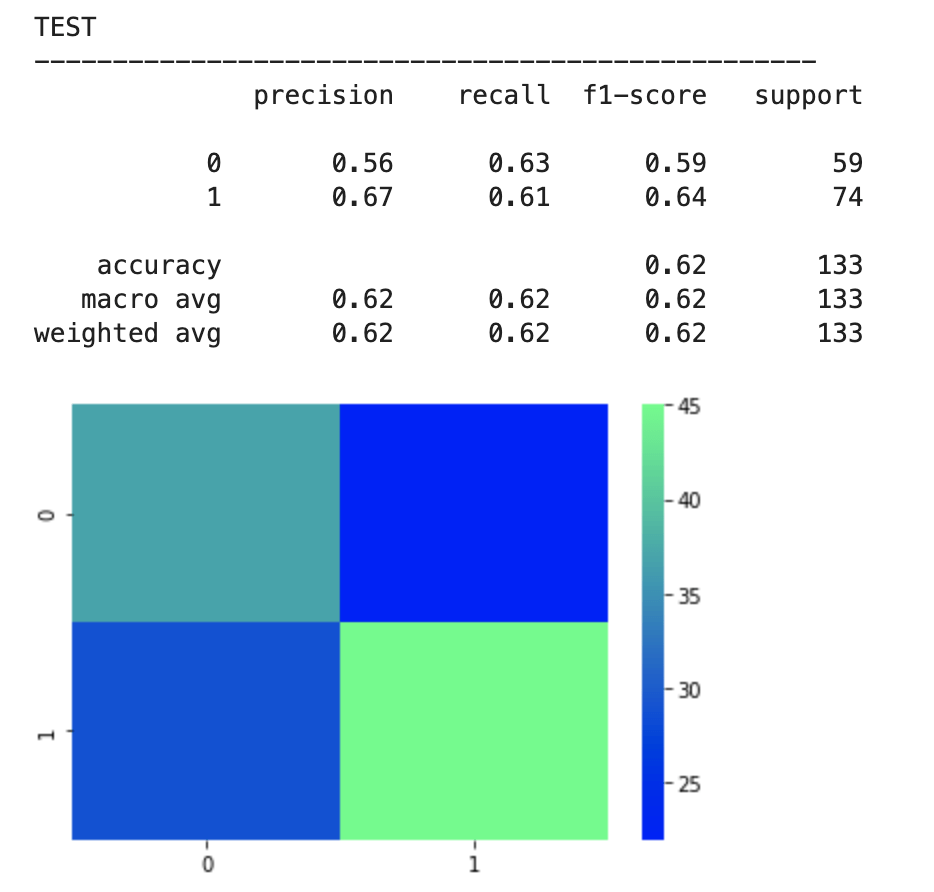

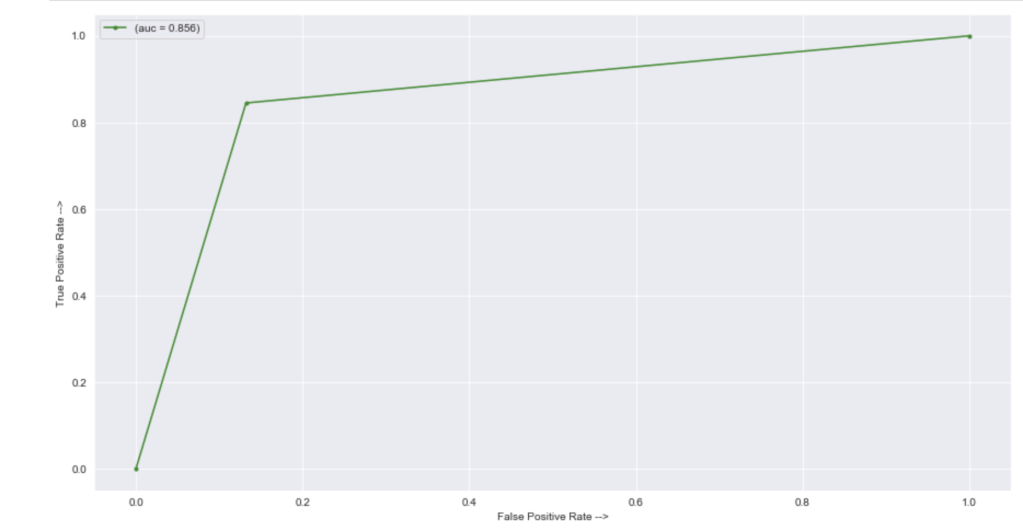

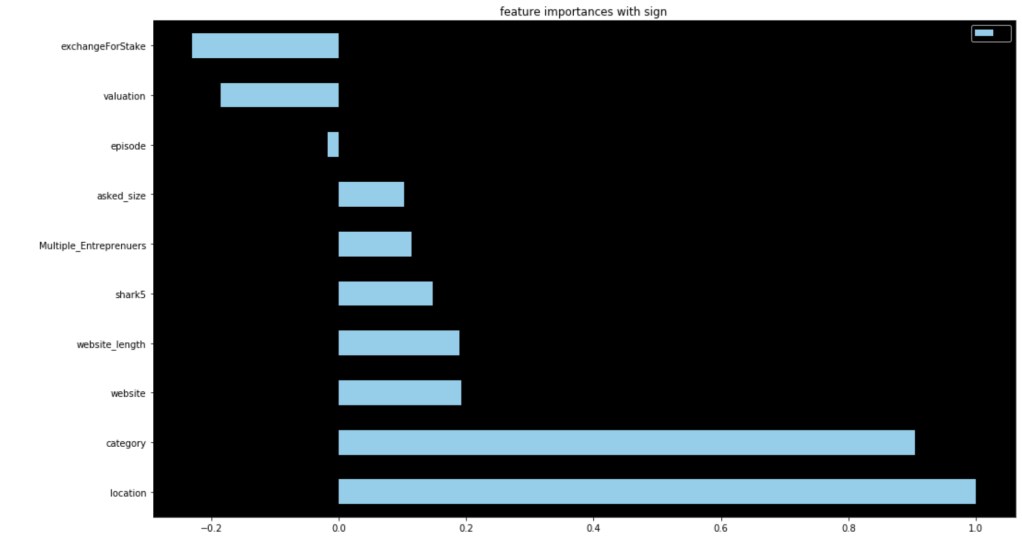

Discrete Models

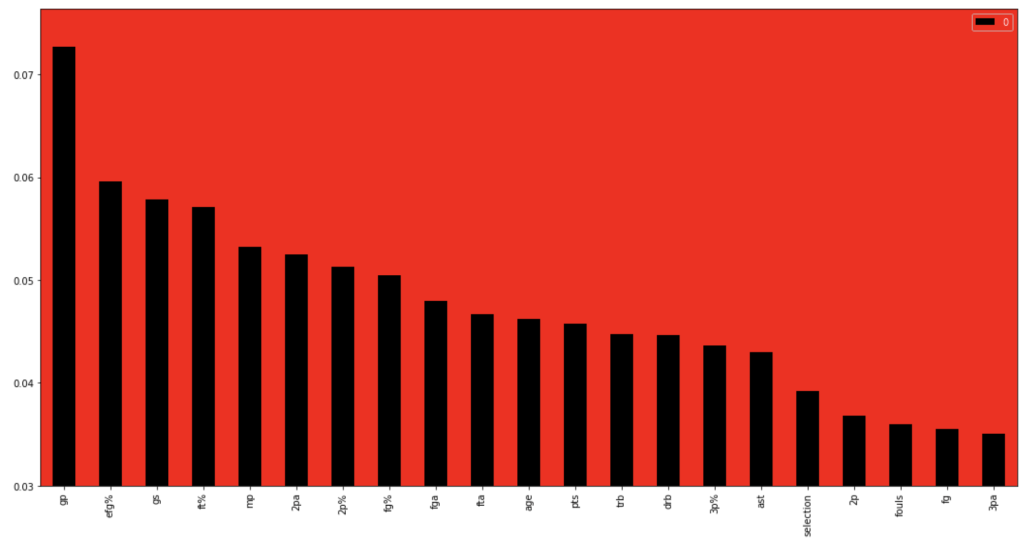

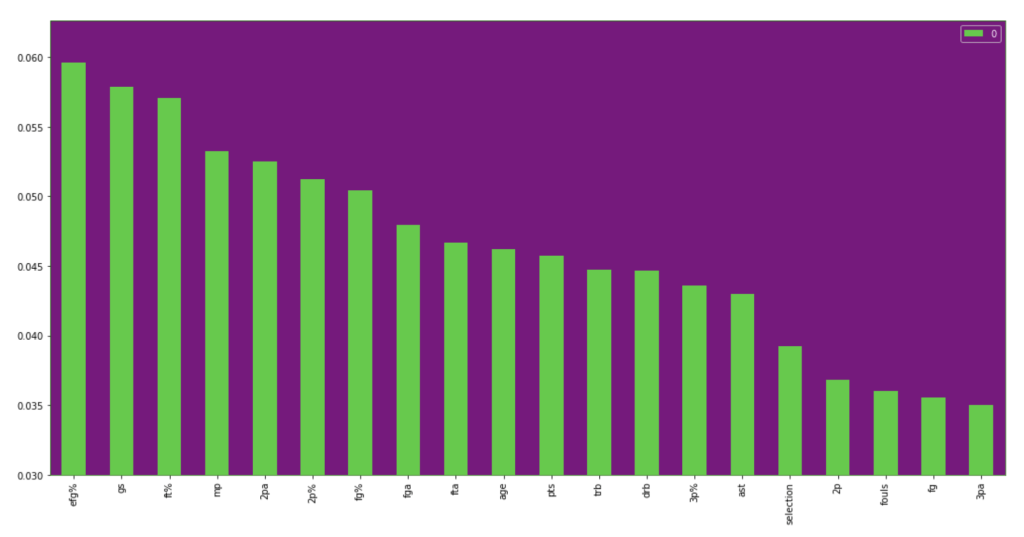

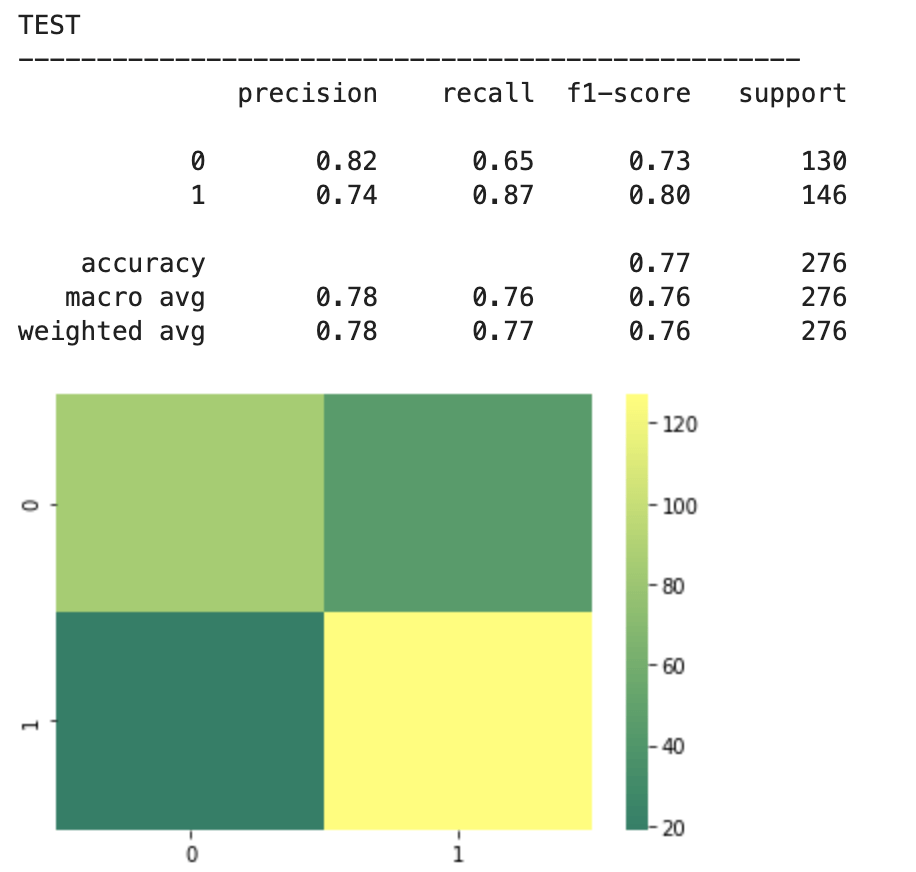

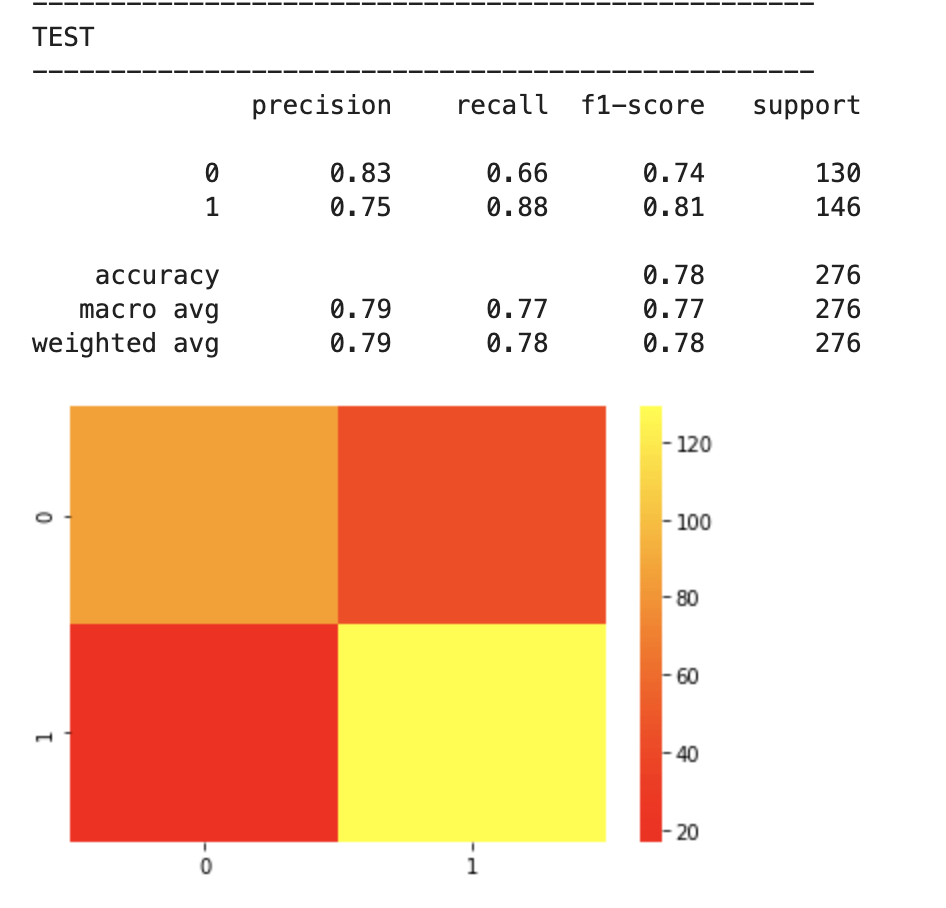

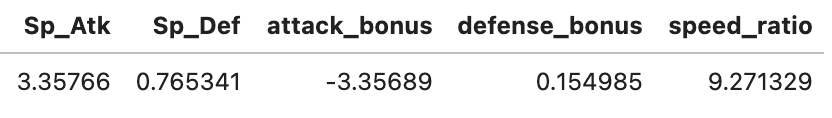

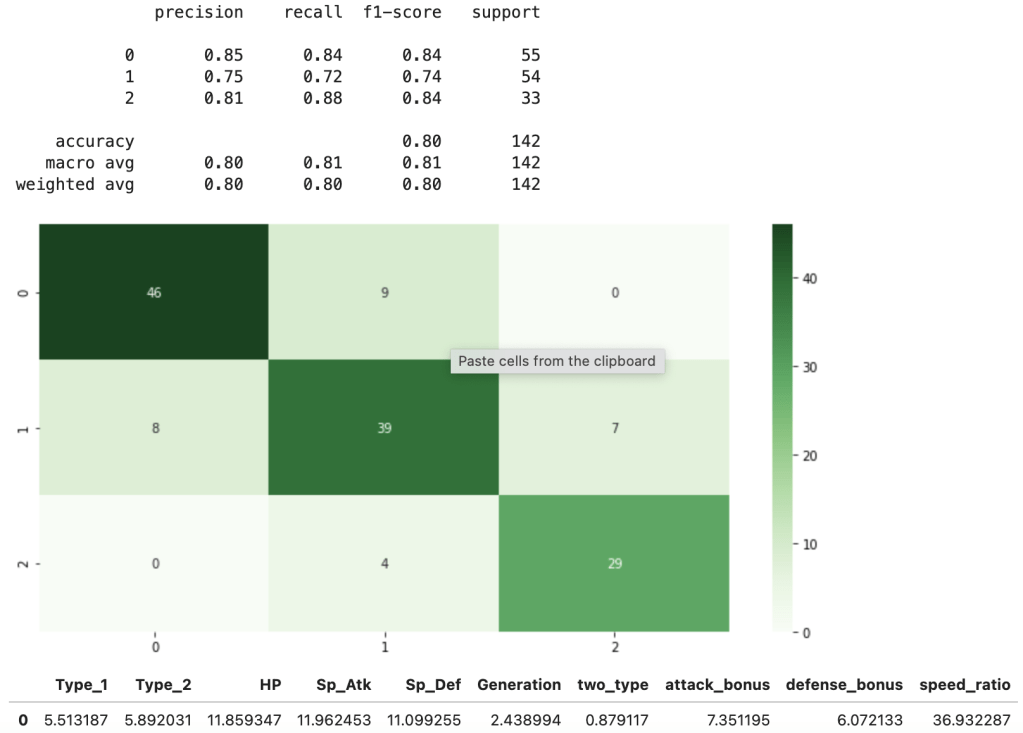

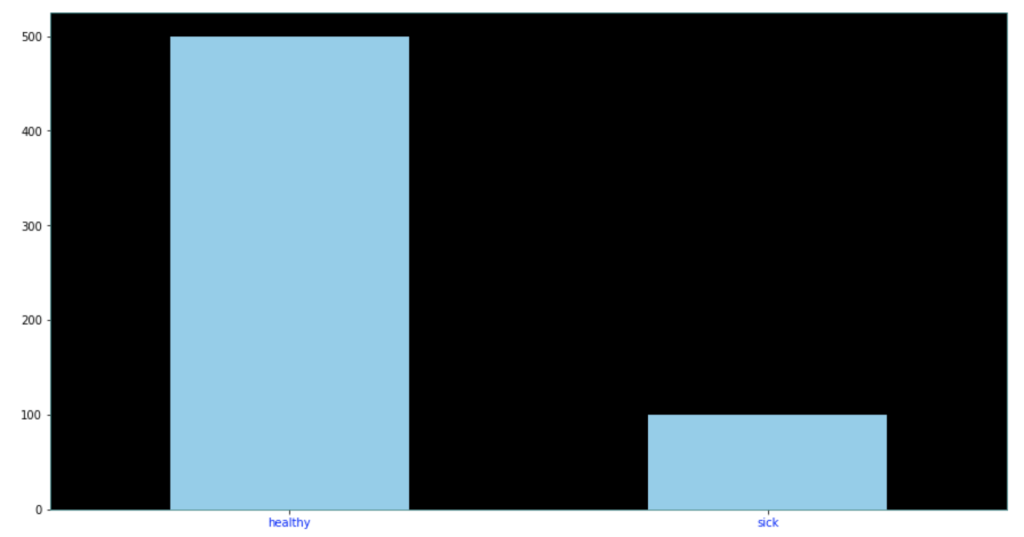

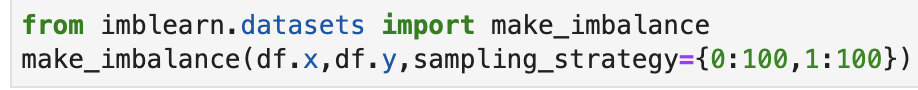

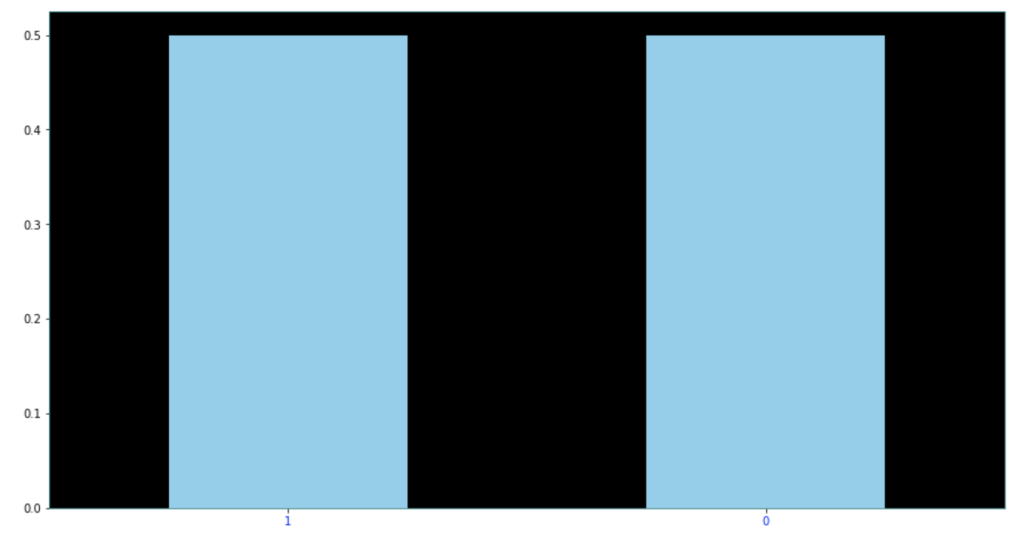

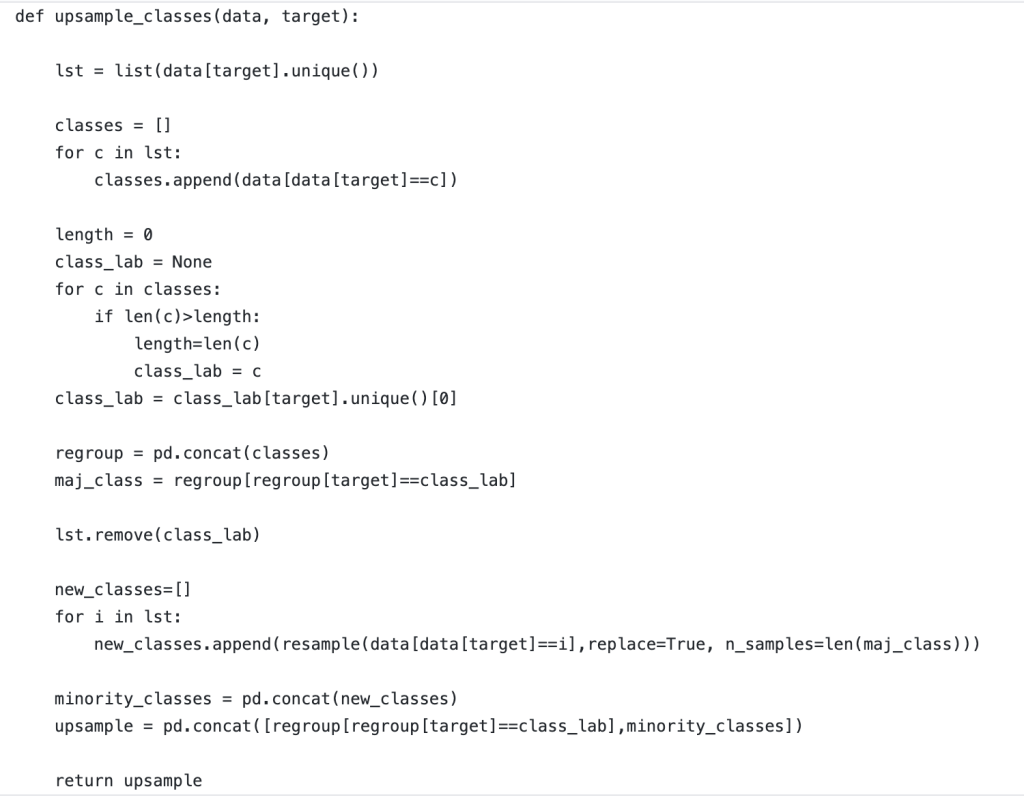

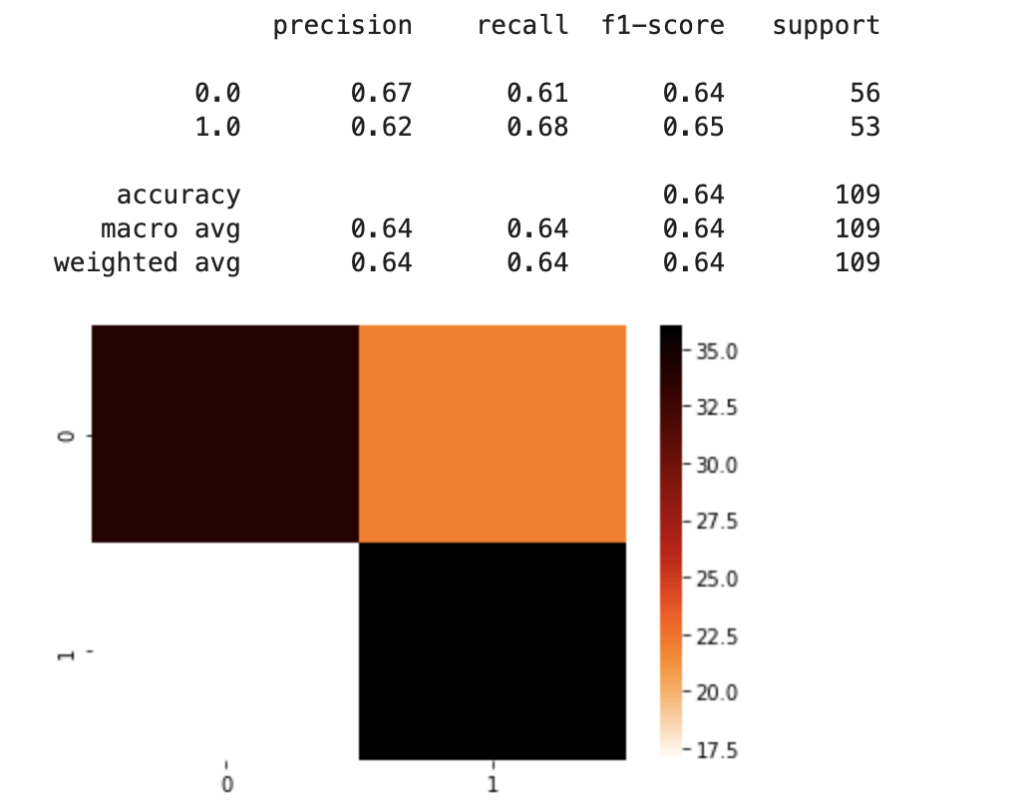

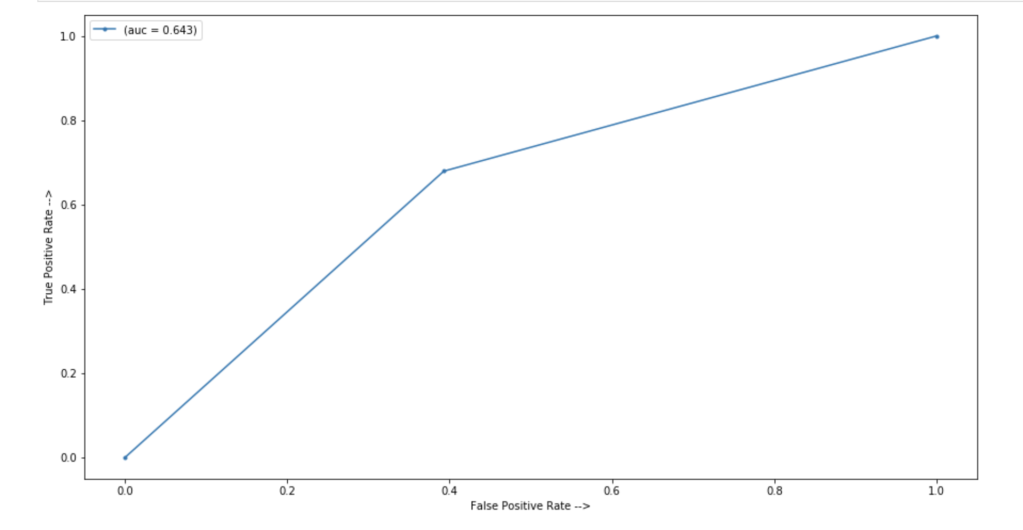

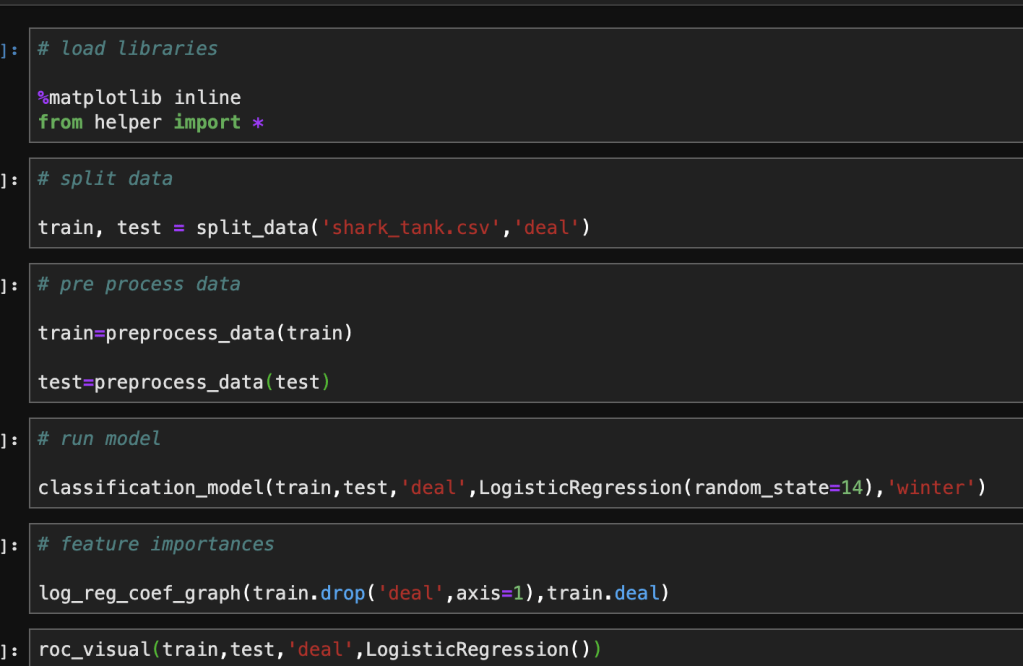

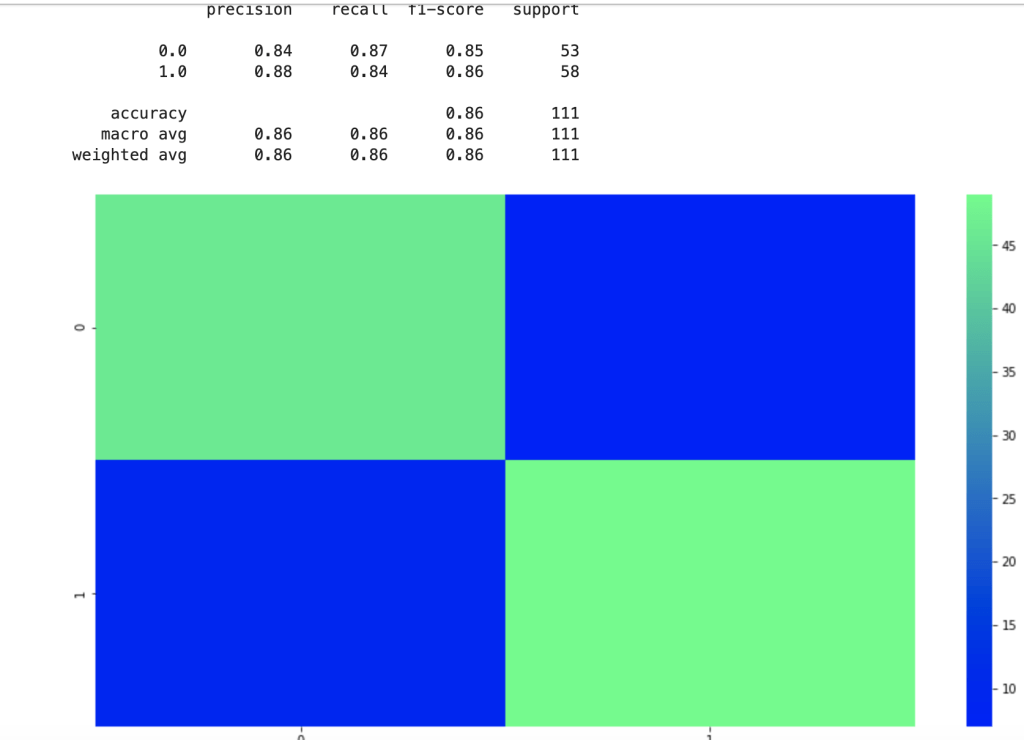

First things first – I need to upsample data. My data was pretty evenly balanced but needed minor adjustments. If you don’t know what I mean by target feature imbalance, check out my blog (on Towards Data Science) over here. Anyway, here comes my best model (notice the features I chose to include):

This shows a strong accuracy at 80% along with a good confusion matrix and interesting feature importances. For more information on what the metrics above, such as recall, actually mean, check out my blog over here.

Next Steps

One-Hot Encoding. I think it would be interesting to learn more about which specific types are the strongest. I plan to update this blog after that analysis so stay tuned.

Neural Network. I would love to run a neural network for both the continuous and discrete case.

Polynomial Model. I would also love to see if polynomial features improve accuracy (and possibly help delete the speed-related features).

Conclusion

For all you Pokémon fans and anyone else who enjoys this type of analysis, I hope you liked reading this post. I’m looking forward to the next 25 years of Pokémon.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19412592/swish_4_.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19412589/swish_3_.png)