Capstone Project at The Flatiron School

Introduction

Thank you for visiting my blog today. Today I would like to discuss my capstone project that I worked on as I graduated from the Flatiron School data science boot camp (Chicago Campus). At the Flatiron School, I began to build a foundation in python and its applications in data science. It was an exciting and rewarding experience. For my capstone project, I investigated insurance fraud using machine learning. After having worked on some earlier projects, I definitely can say that this one was a bit more complete and suiting of a capstone project. I’d like to take you through my process and share what insights I gained and what problems I faced along the way. I’ve since worked on some other data science projects and have expanded my abilities in areas such as exploratory data analysis (EDA from henceforth) and this project represents where I had progressed as of my 4th month into data science. I’m very proud of this project and hope you enjoy reading this blog.

Data Collection

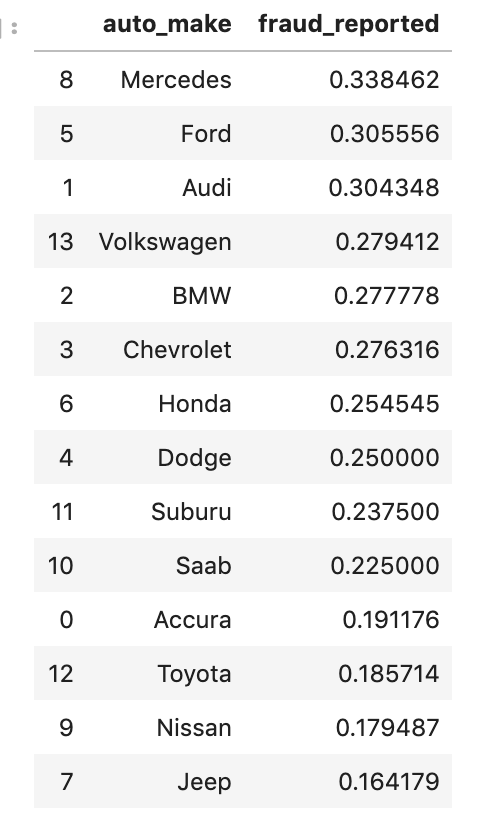

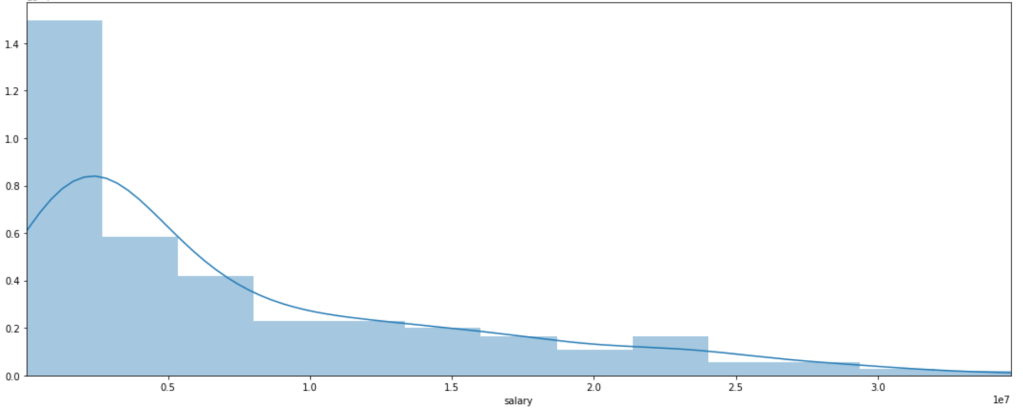

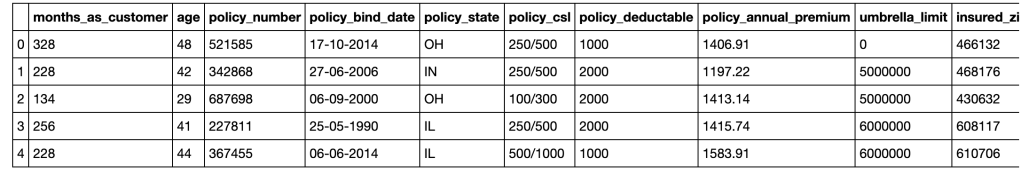

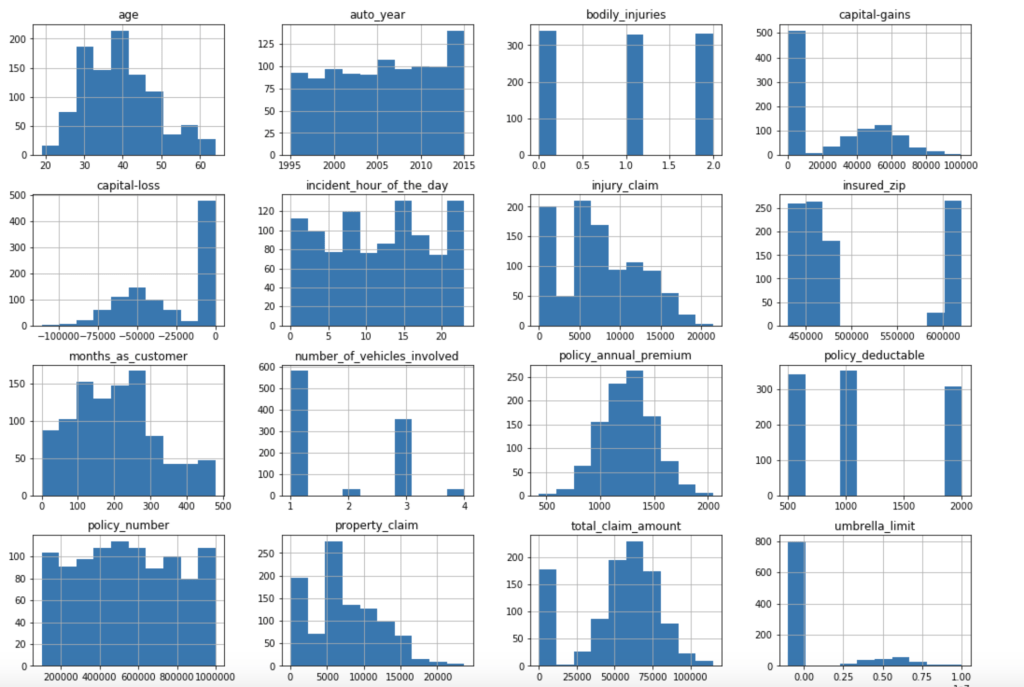

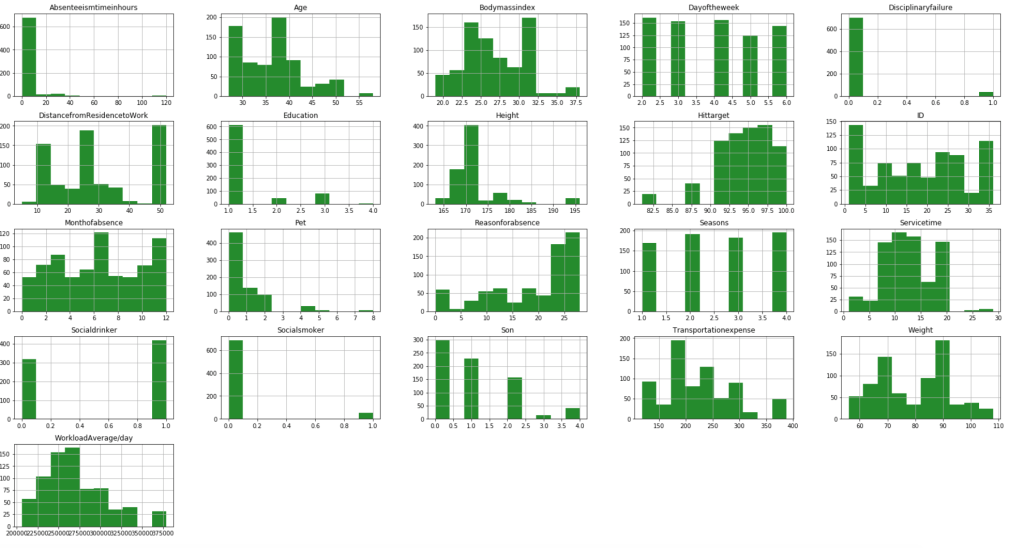

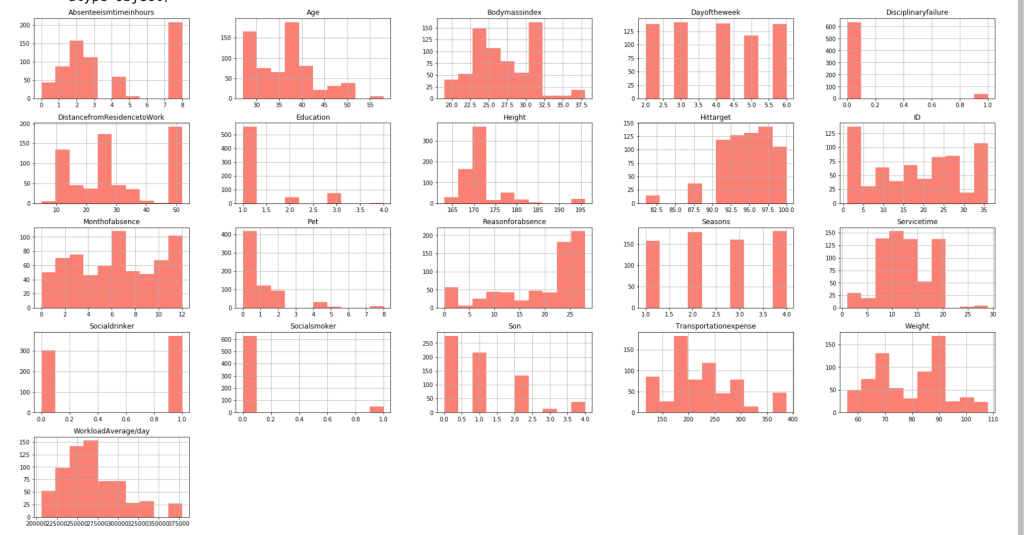

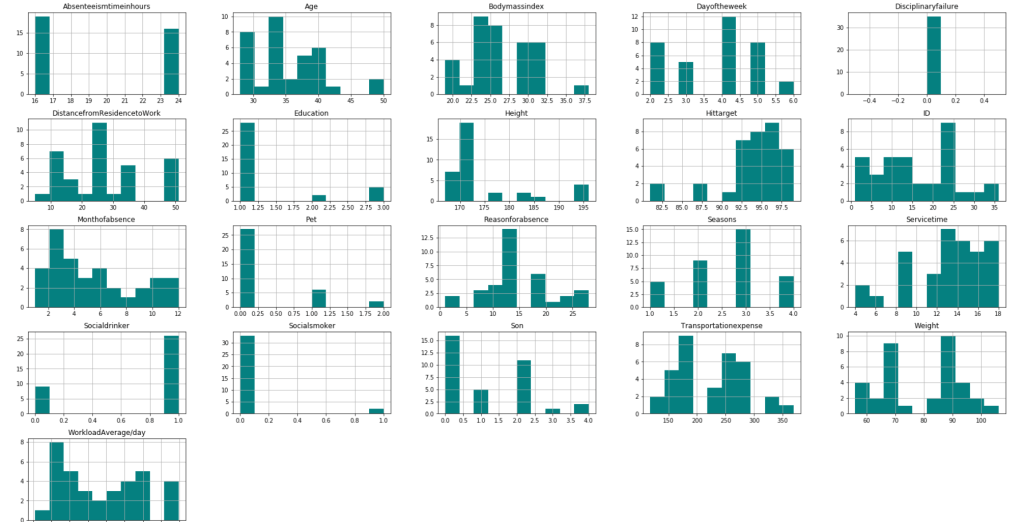

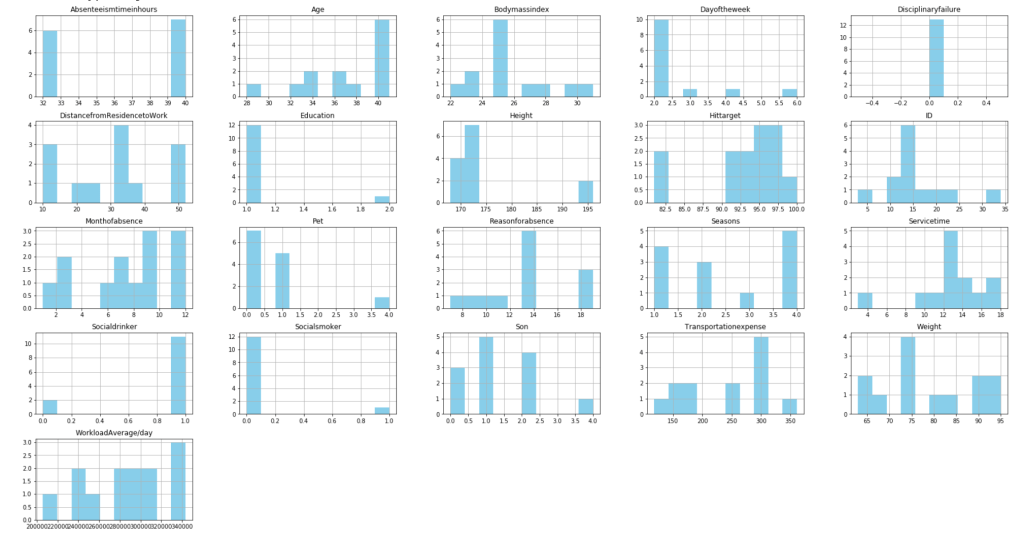

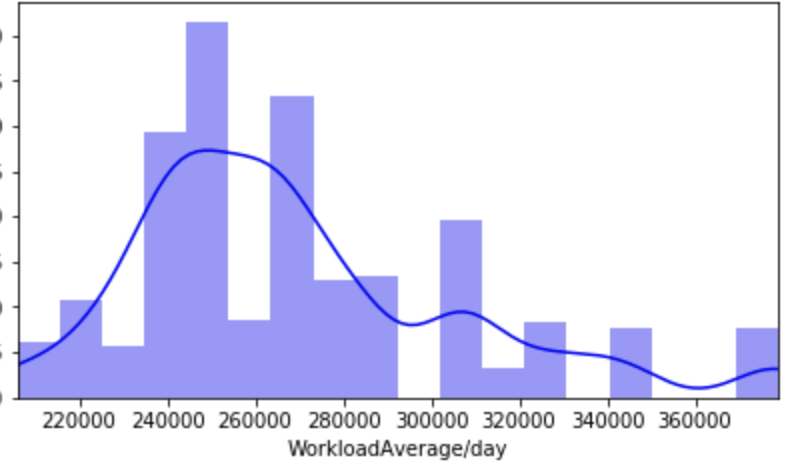

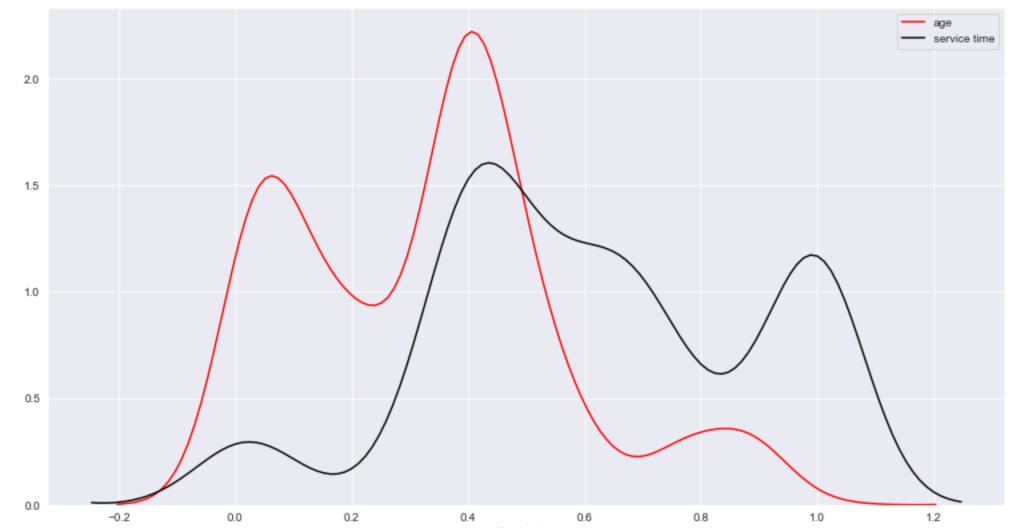

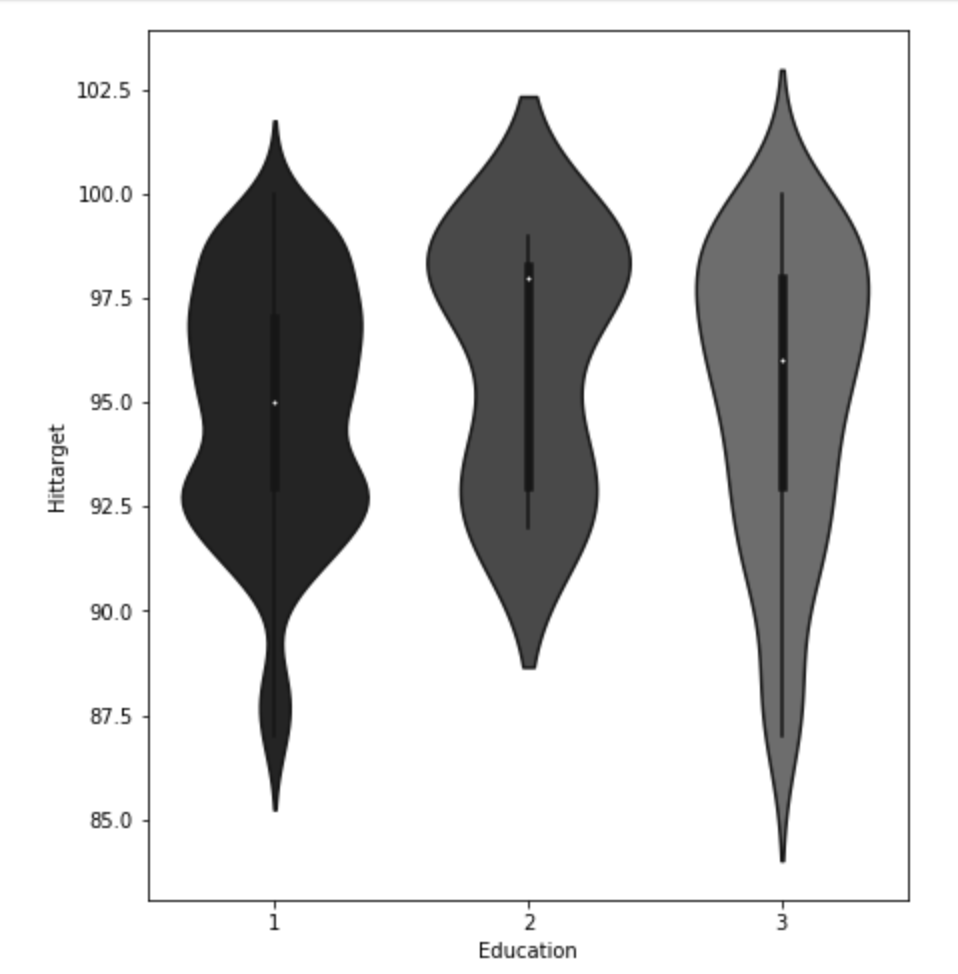

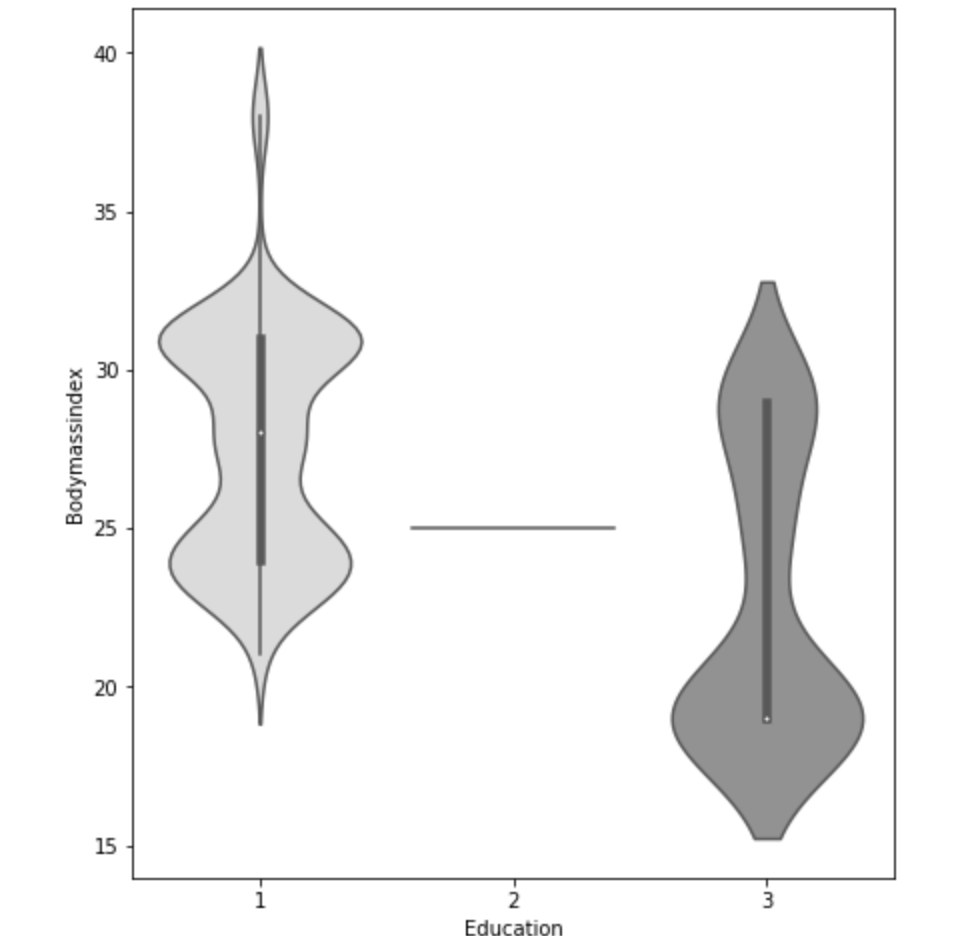

My data comes from kaggle.com, a site with many free data sets. I added some custom features but the ones that came from the initial file are as follows (across 1000 observations): months as customer, age, policy number, policy bind date, policy state, policy csl, policy deductible, policy premium, umbrella limit, zip code, gender, occupation, education level, relationship to policy owner, capital gains, capital losses, incident date, incident type, collision type, incident severity, authorities contacted, incident state, incident city, incident location, incident hour of the day, number of vehicles involved, property damage, witnesses, bodily injuries, police report available, total claim amount, injury claim, property claim, vehicle claim, car brand, model, car year, and the target of feature of whether or not the report was fraudulent. The general categories of these features can be described as: incident effects, policy information, incident information, insured information, car information. (Here’s a look at a preview of my data and some histograms of explicitly numerical features).

Data Preparation

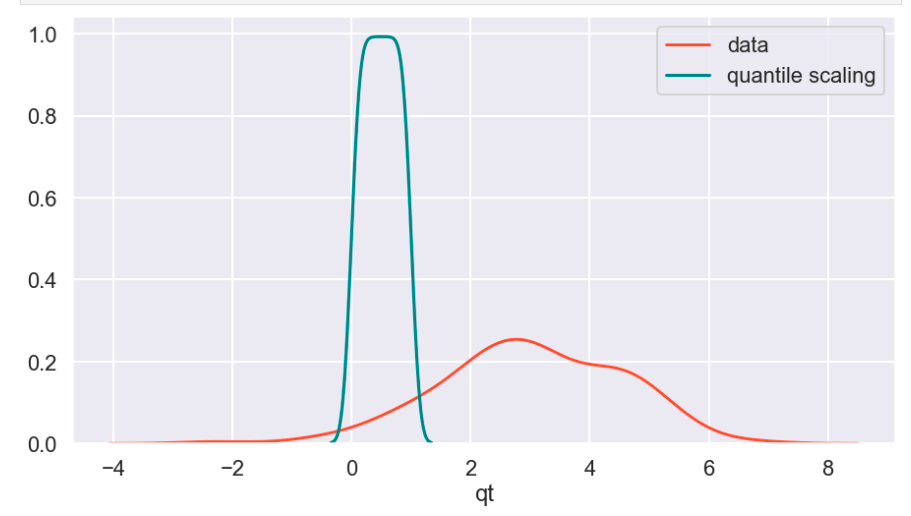

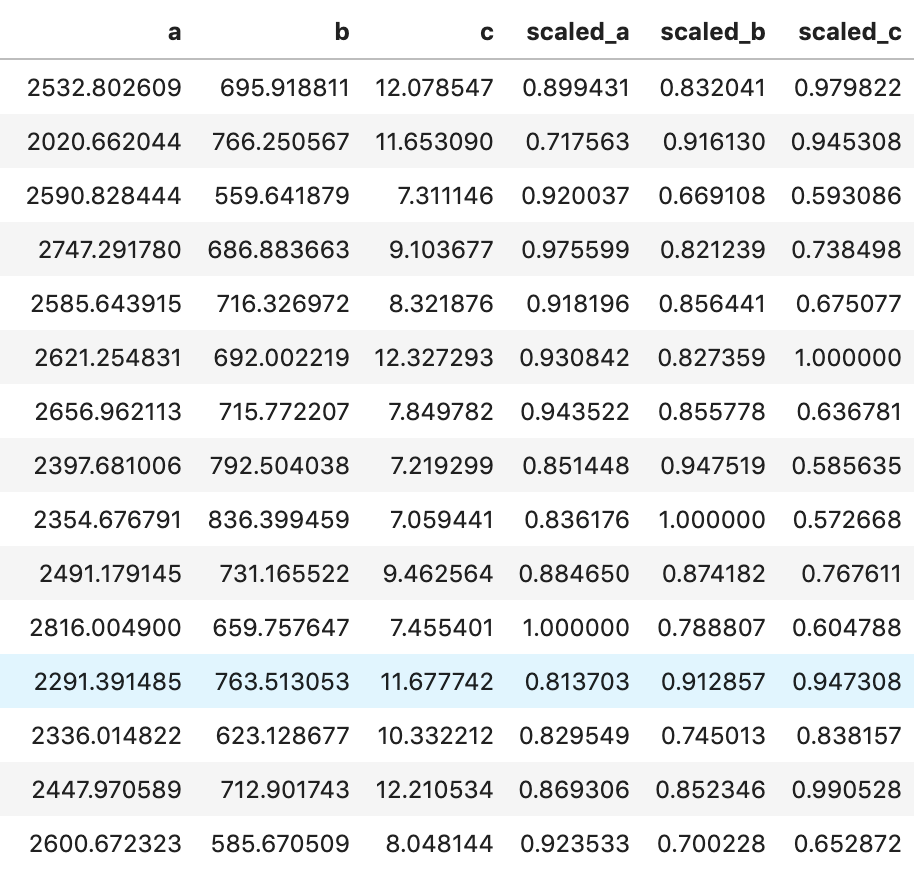

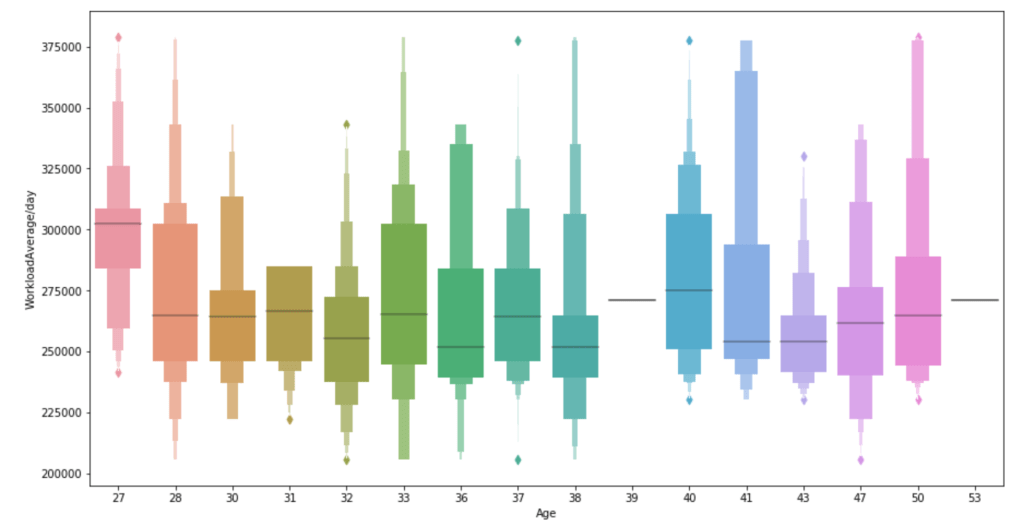

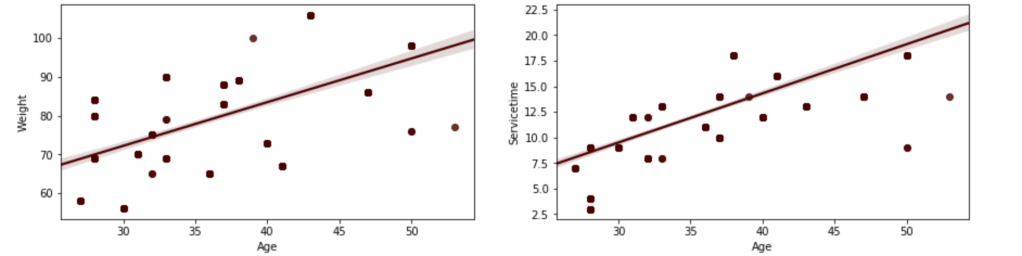

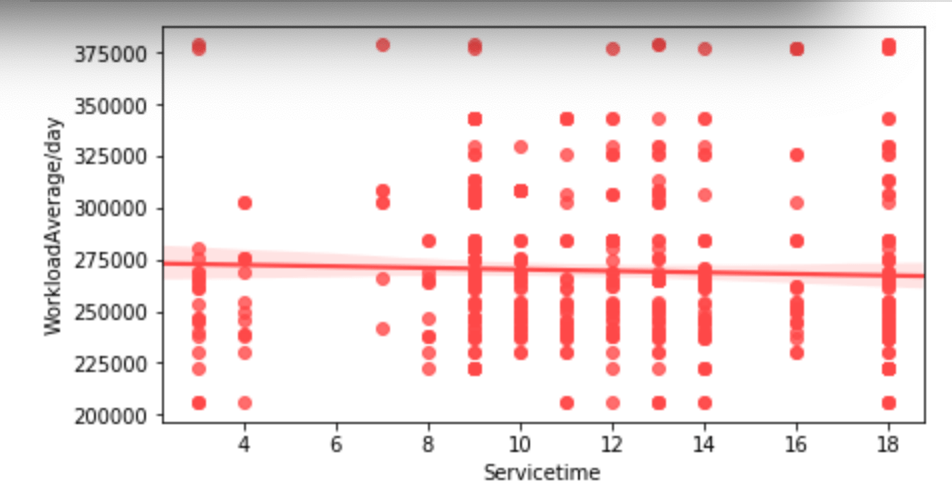

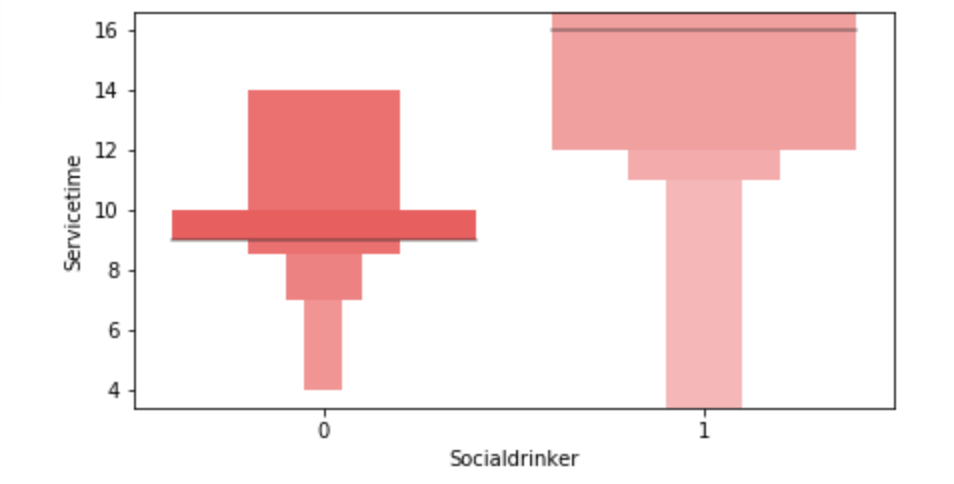

There weren’t many null values and the ones present were actually expressed in an unusual way, but in the end I was able to quickly deal with these values. After that, I encoded binary features in 0 and 1 form. I also broke down policy bind date and incident date into month and year format as day format was not general enough to be meaningful. I also added a timeline variable between policy bind and incident date. I then mapped a car type to each car model such as sedan or SUV. Next, I removed age, total claim amount, and vehicle claim from the data due to correlation with other features. I then was ready to encode my categorical data. Here, I used a new method I had never really used before and I discuss this process in detail in another blog on my website. I then revisited correlation having converted all my features to numeric values and remove incident type from my data. I performed very short exploratory data analysis that does not really warrant discussion. (This is one big change I have taken since doing more projects. EDA is a very exciting part of the data science process and provides exciting visuals, however at the time I was very focussed on modeling). (I’ll include one visual to show my categorical feature encoding).

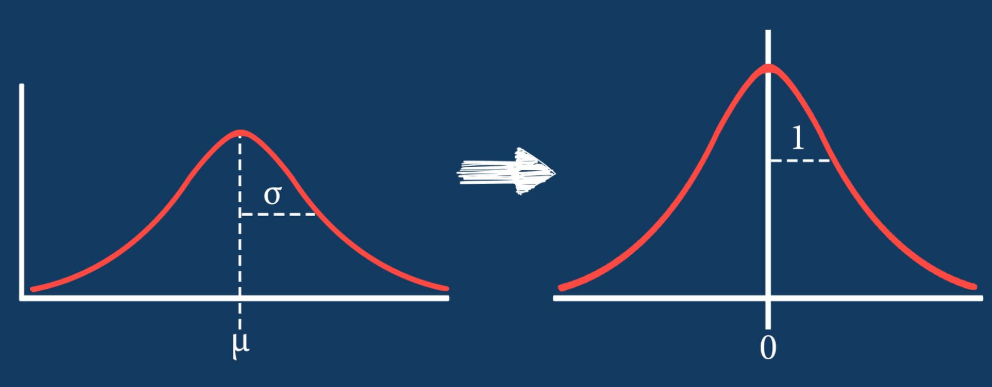

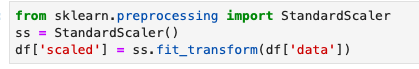

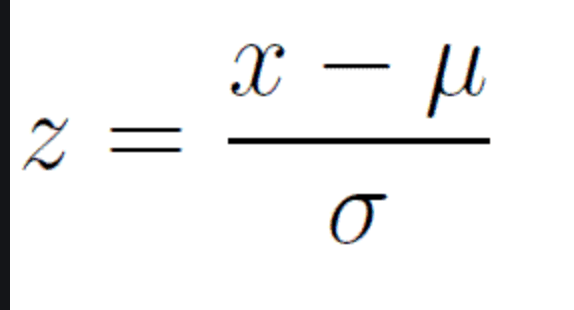

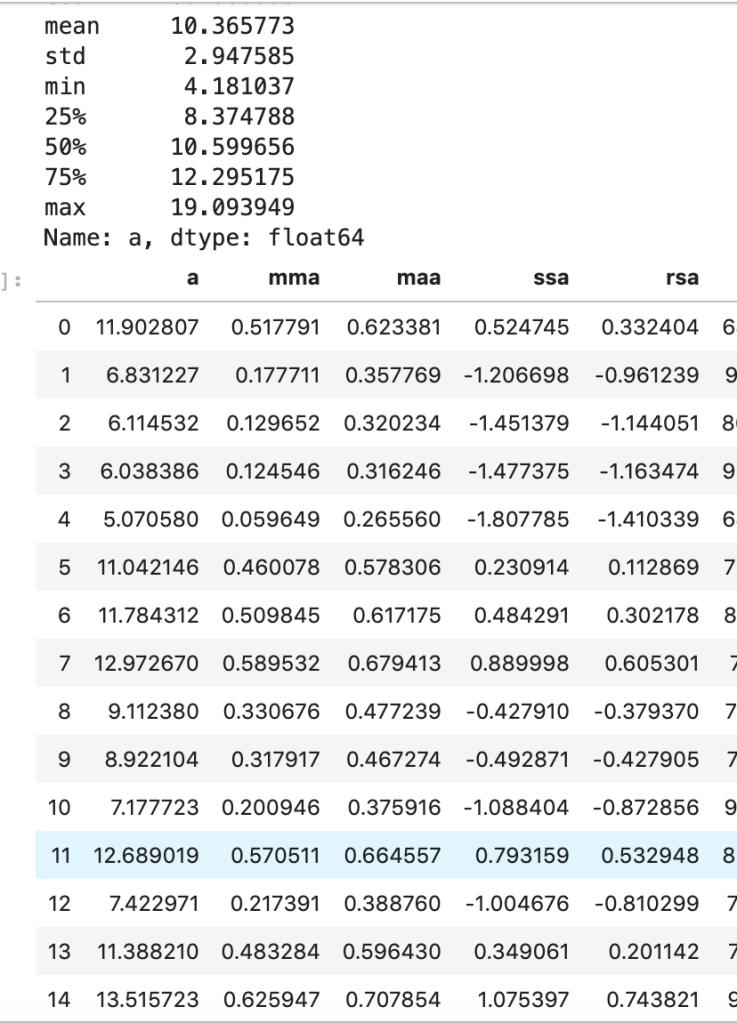

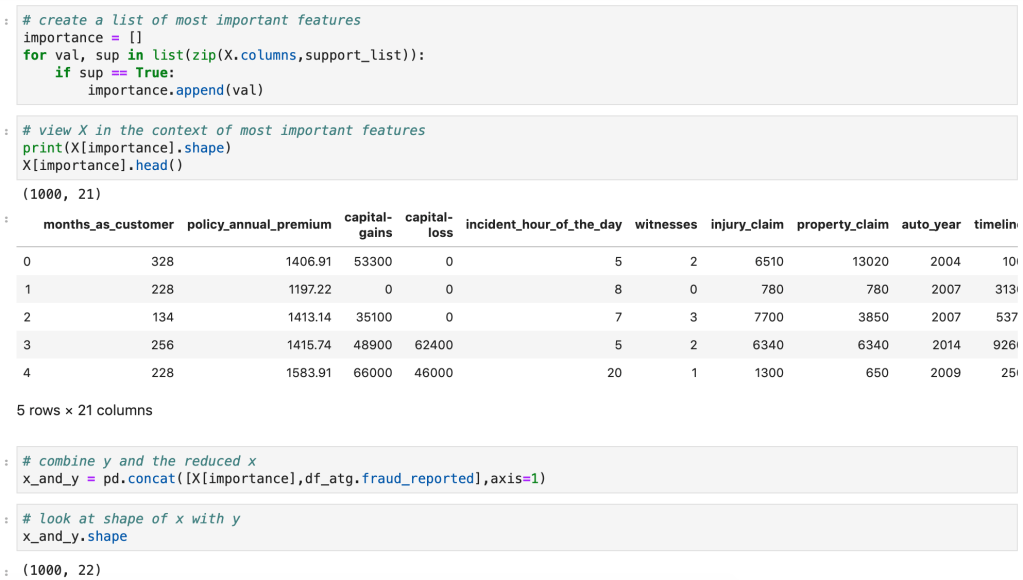

Feature Selection

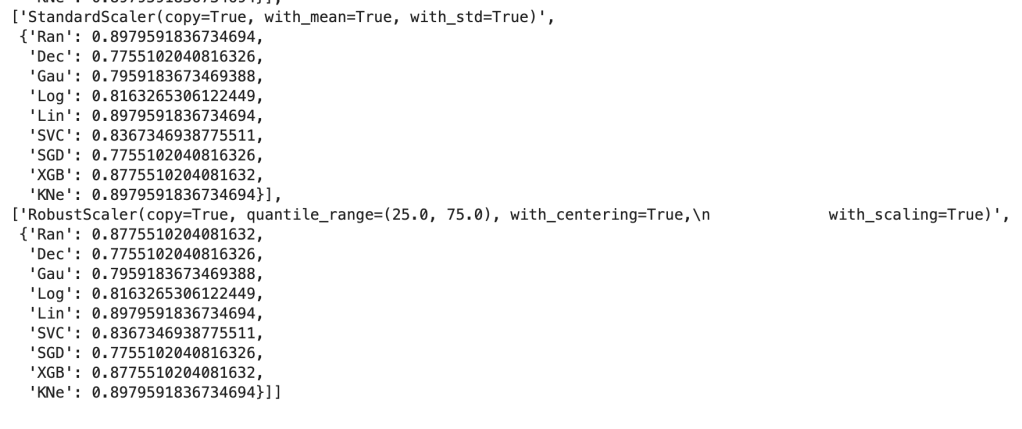

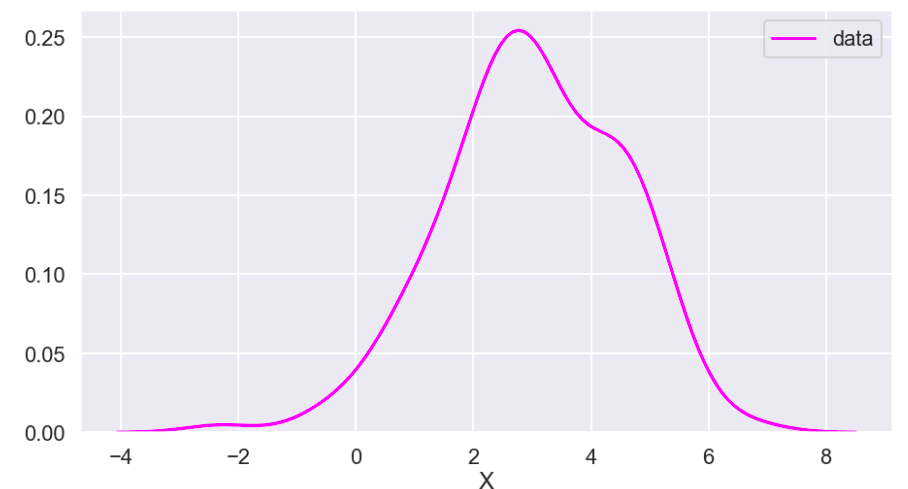

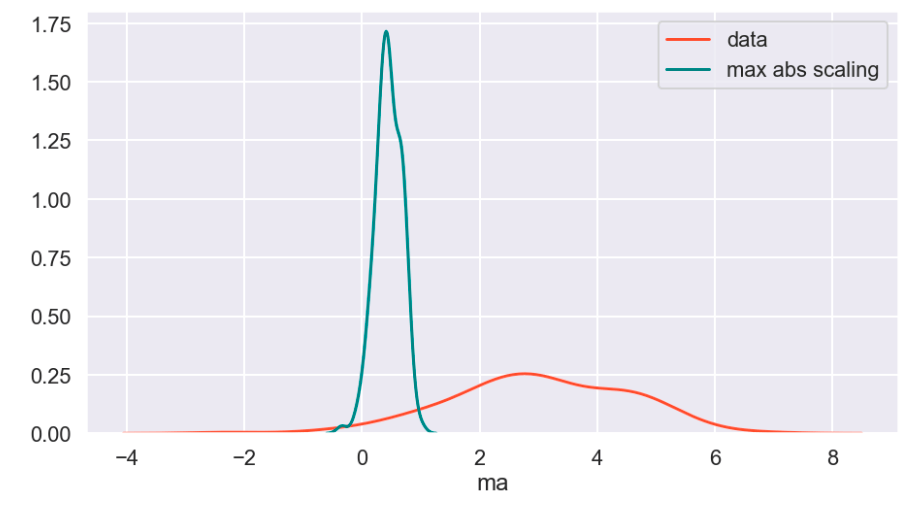

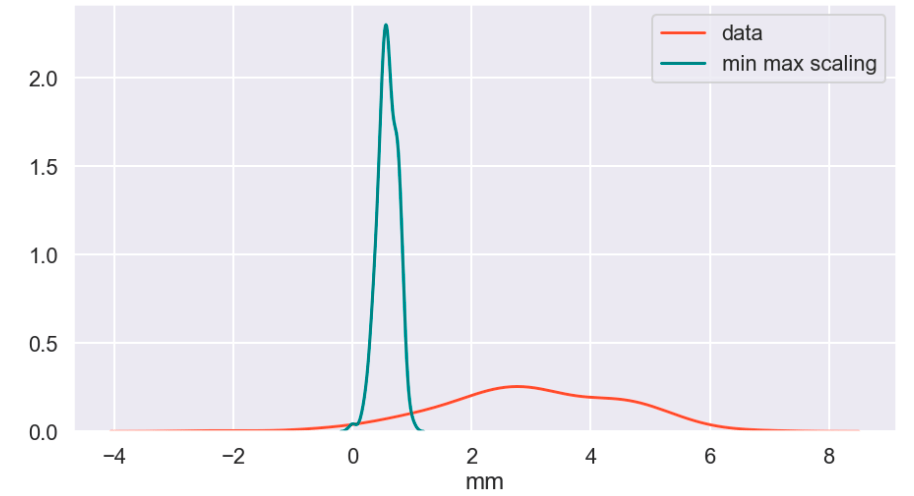

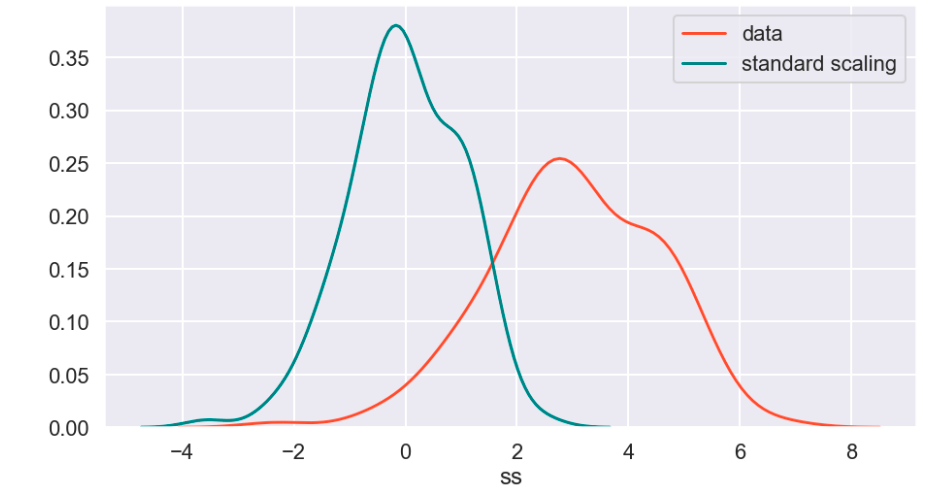

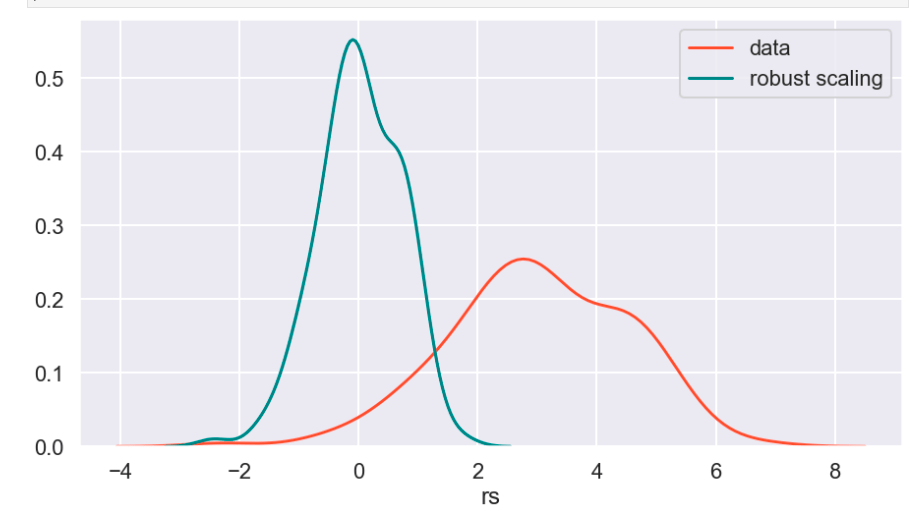

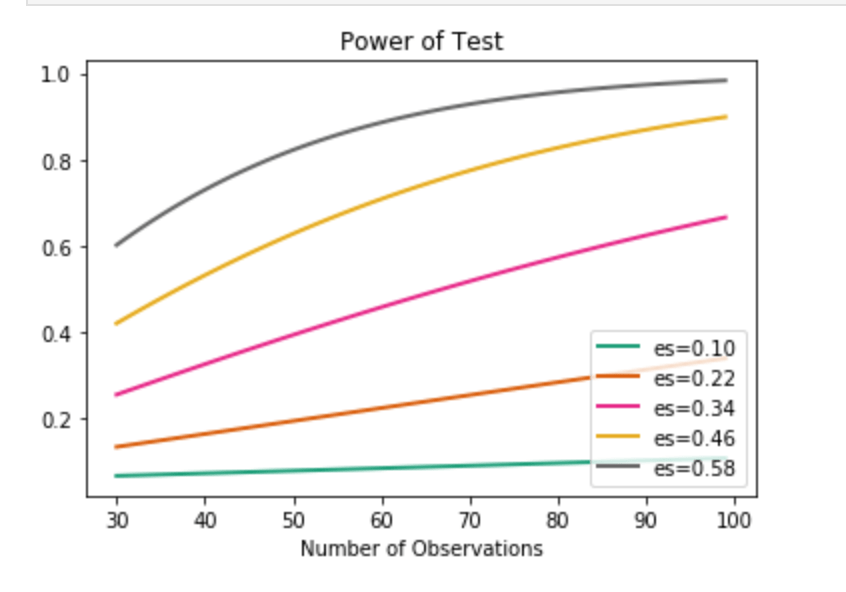

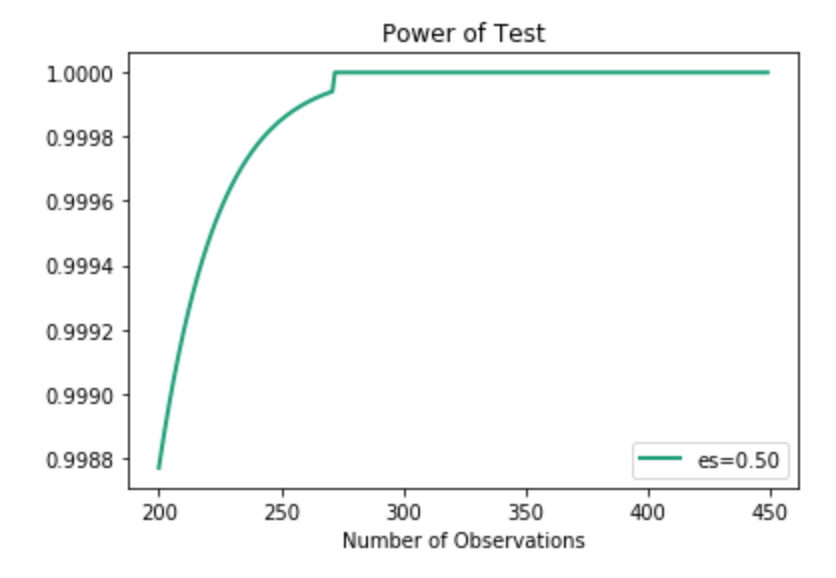

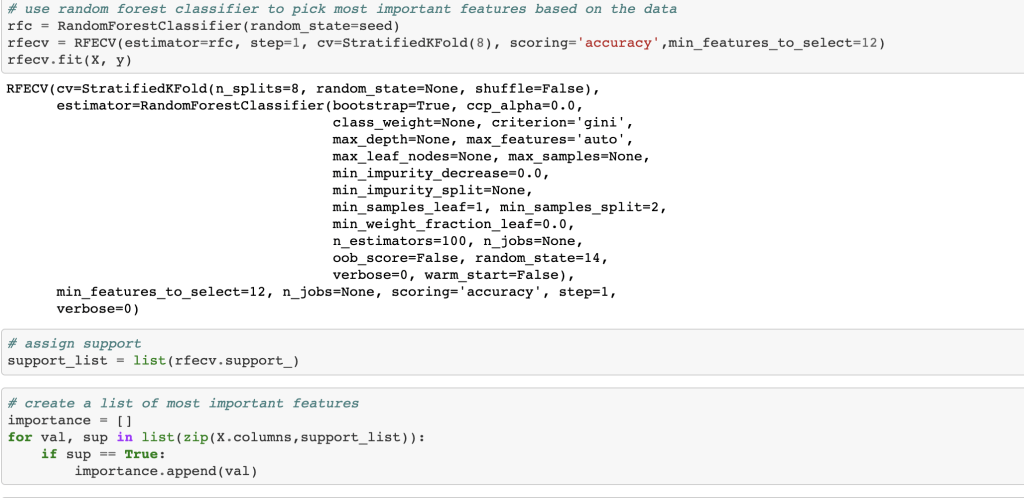

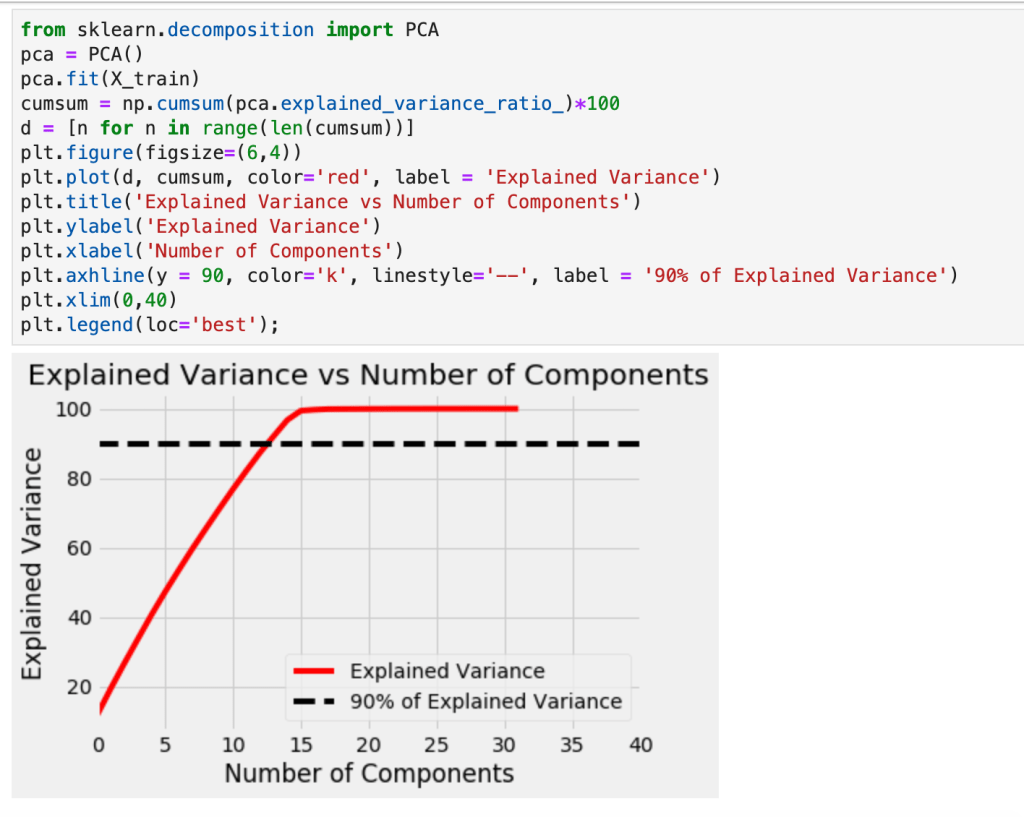

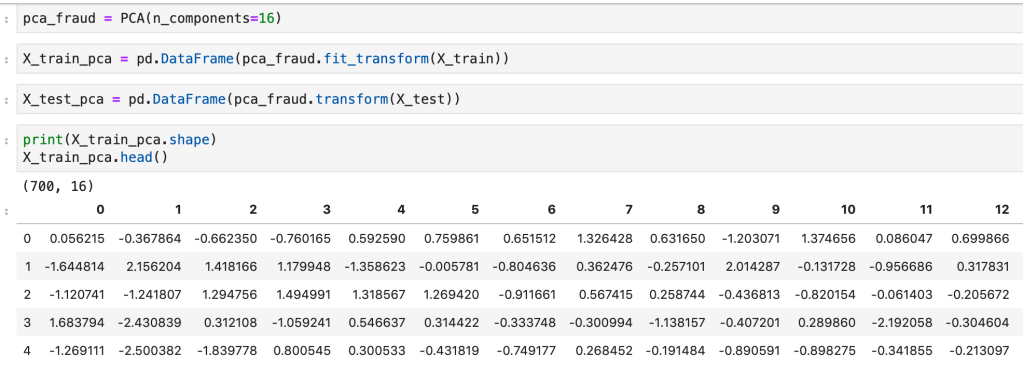

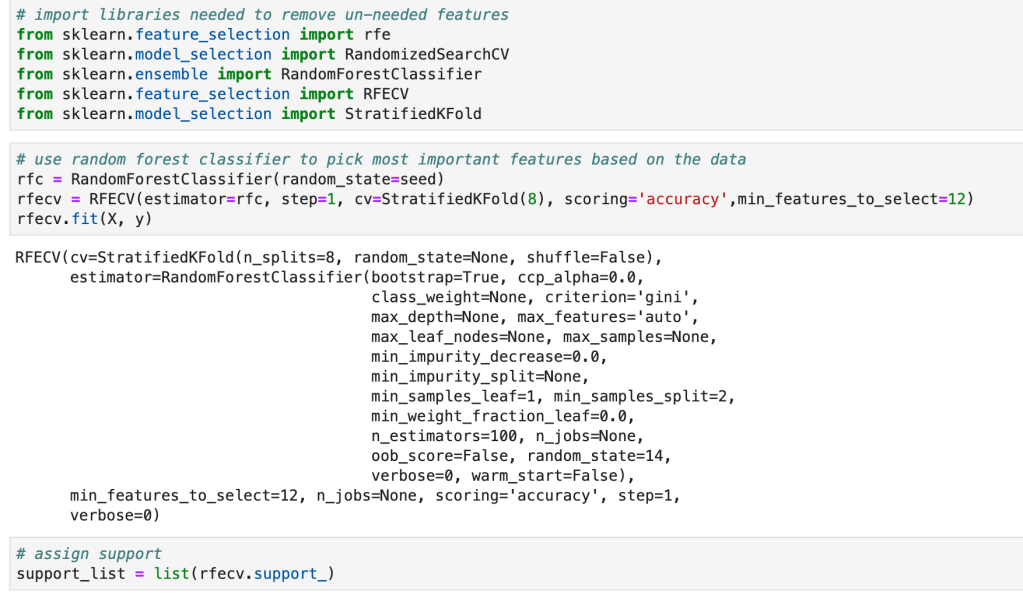

Next, I ran a feature selection method to reduce overfitting and build a more accurate model. This was very important as my model was not working well early on. The other item that helped improve my model was the new type of categorical feature encoding. To do this, I ran RFE (I have a blog about this) using a random forest classifier model (having already run this project and found random forest to work best, I went back and used it for RFE) and reduced my data to only 22 features. After doing this, I filtered outliers, scaled my data using min-max scaling, and applied Box-Cox transform to normalize my data. Having done this, I was now ready to split my data into a set with which to train a model and a separate set with which to validate my model. I also ran PCA but found RFE to work better and didn’t keep my PCA results. (Here’s a quick look at how I went about RFE).

Balancing Data

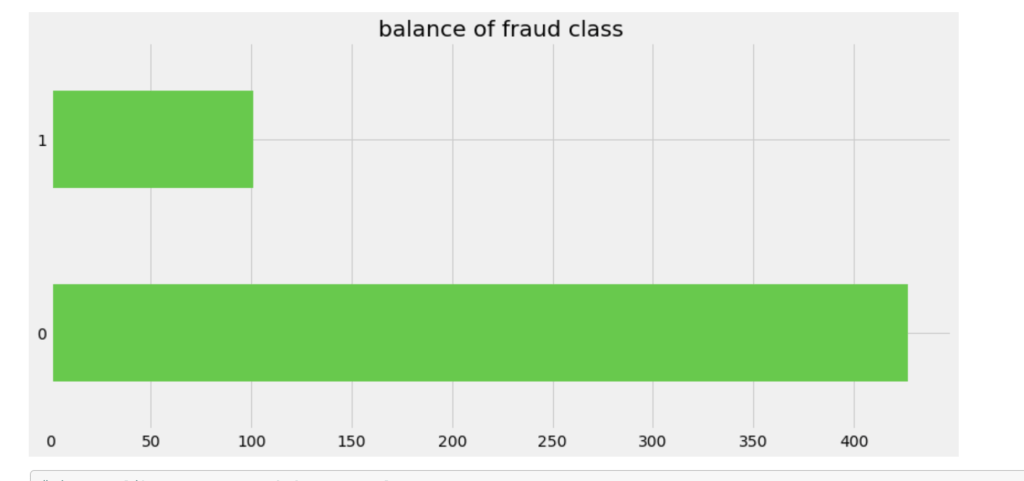

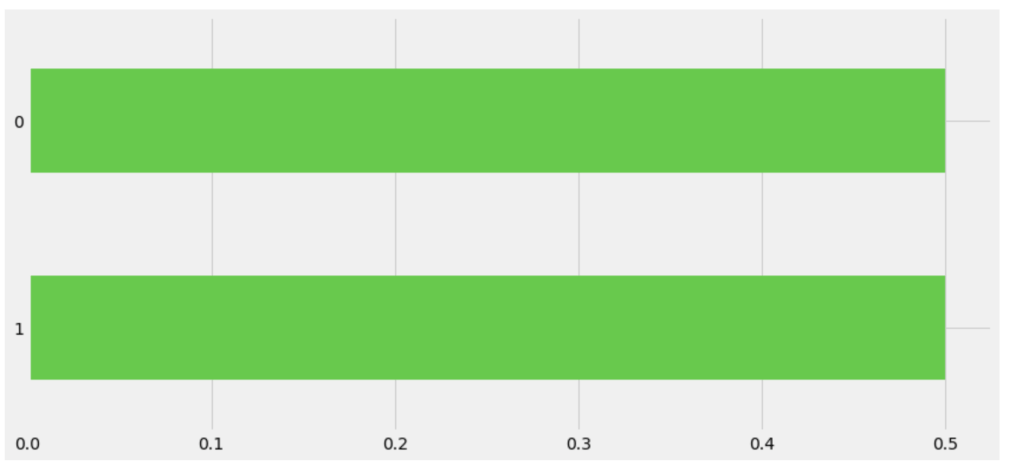

One common task in the data science process is balancing your data. If you are predicting a binary outcome, for example, you may have many values of 0 and very few values of 1 or vice-versa. In order to have an accurate and representative model you need to have the same amount of 1 values and 0 values when training your models. In my case, there were a lot more cases that involved no fraud compared to those that involved fraud. I artificially created more cases that were fraudulent to have a more evenly distributed model.

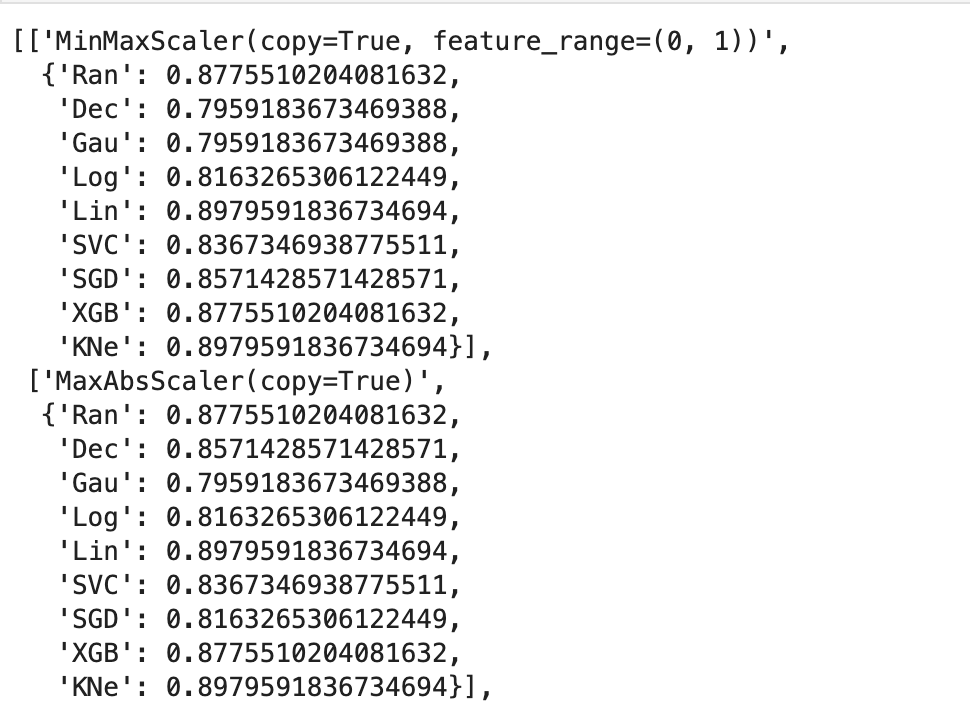

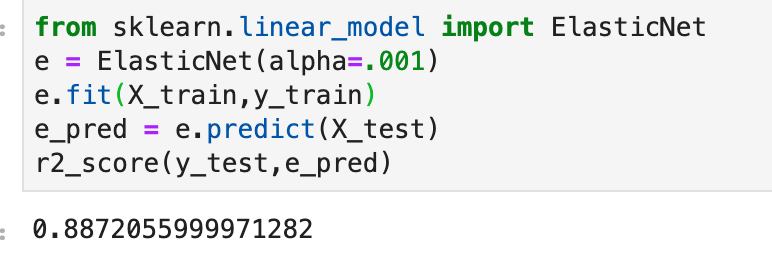

Model Data

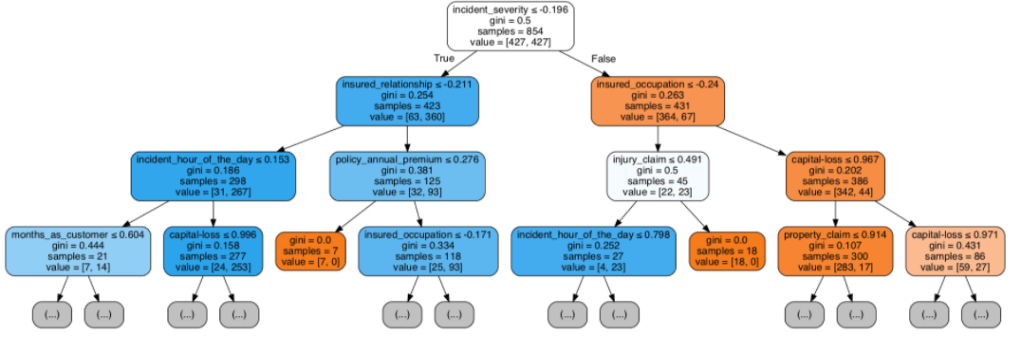

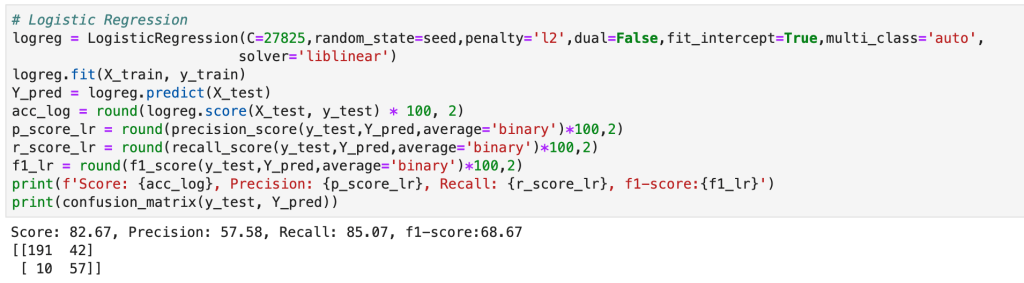

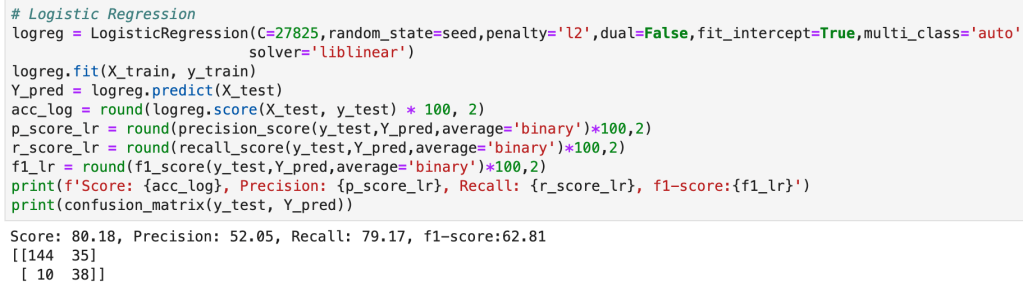

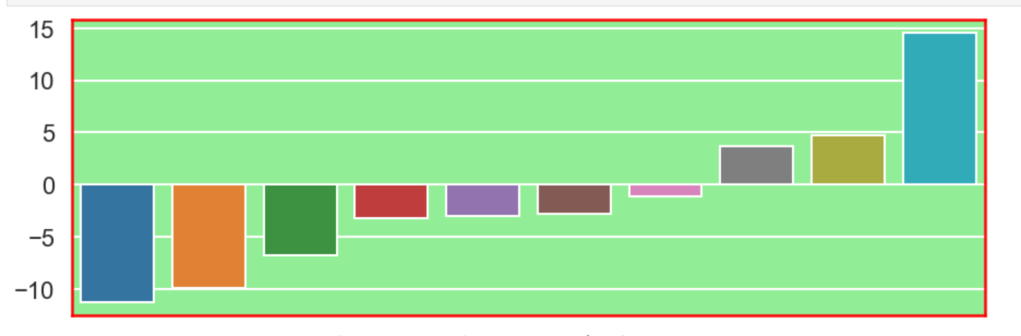

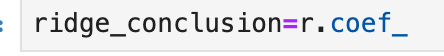

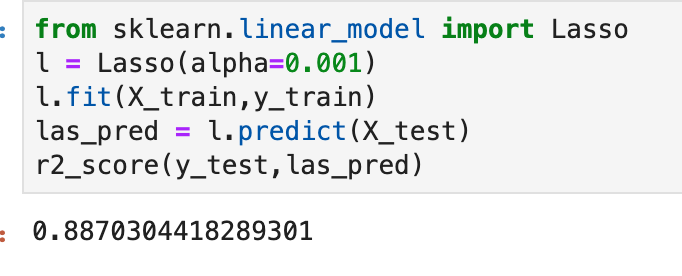

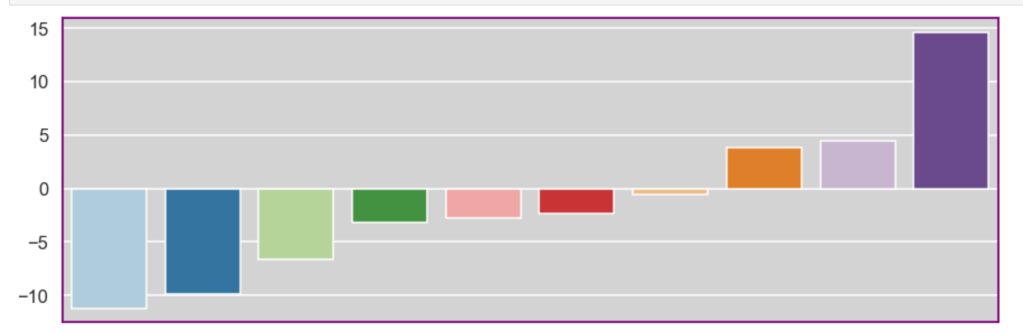

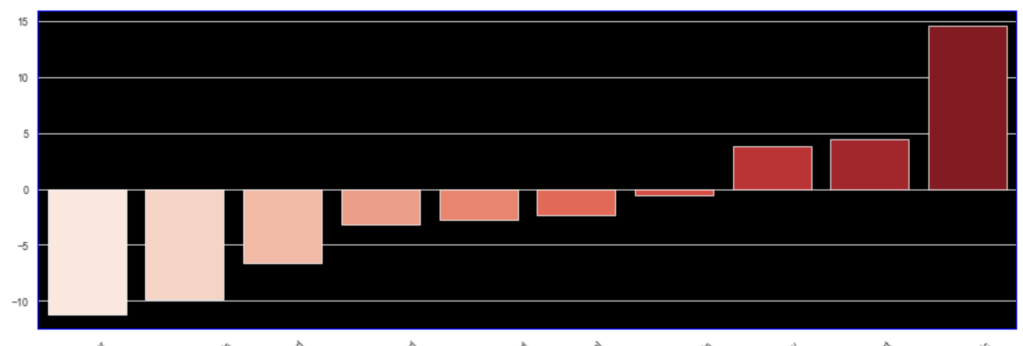

Having prepared all my data, I was now ready to model my data. I ran a couple of different models while implementing grid-search to get optimal results. I found the random forest model to work best with ~82% accuracy. My stochastic gradient descent model had ~78% accuracy but had the highest recall score at ~85%. This recall score matters as it captures how often fraud is identified when the case is actually a case that involved fraud (and not just a case that is said to be fraud but isn’t – recall is the true positives divided by true positives plus false negatives or fraud identified divided by fraud identified and fraud not identified). The most indicative features of potential fraud in order were: high incident severity, property claim, injury claim, occupation, and policy bind year. Here’s a quick decision tree visual:

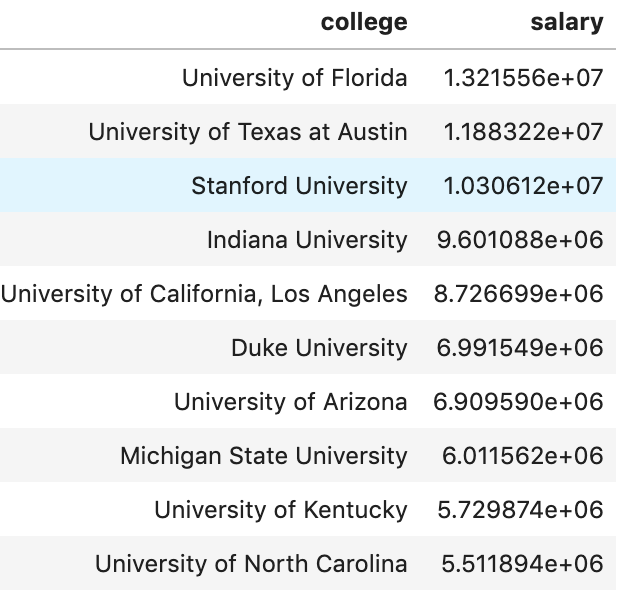

Here is the leading indicators sorted (top ten only):

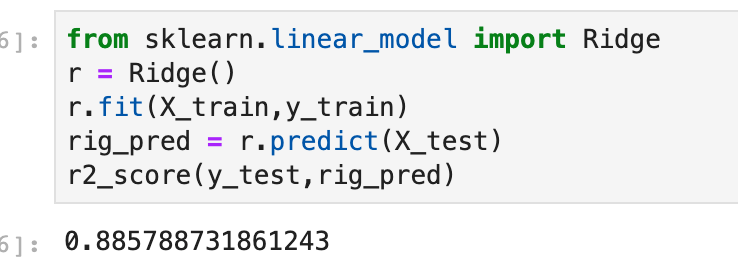

Other Elements of the Project

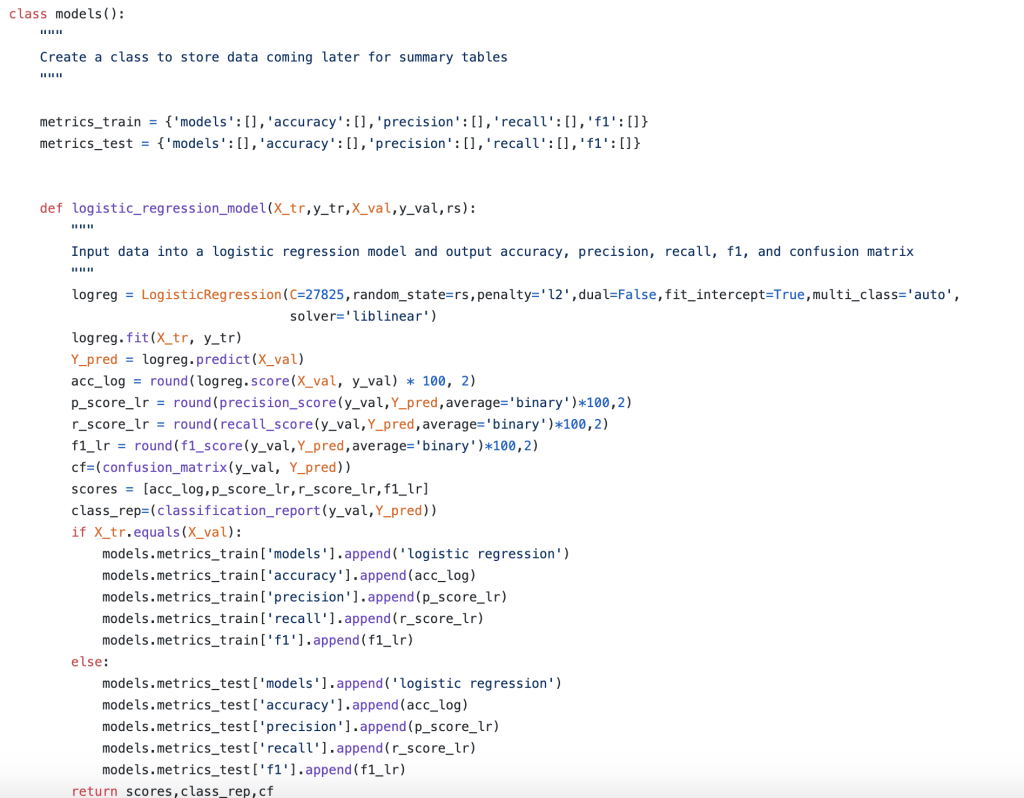

In addition to my high level process, there were many other elements of my capstone project that were not present in my other projects. The main item I would like to focus on is the helper module. The helper module (this may have a more proper term but I am just going to call it a helper module) was where I wrote 700 lines of backend code to create functions that would automate everything I wanted to happen in my project. I even used classes to organize things. This may sound basic to some readers, but I don’t really use classes that often. The functions I wrote were designed to be robust and not specific to my project (and I have actually been able to borrow a lot of code from that module when I have gotten stuck in recent projects). Having created a bunch of custom functions I was now able to compress my entire notebook where I did all my work into significantly fewer cells of code. Designing this module was difficult but was ultimately a rewarding experience. I think the idea of a helper module is valuable since you want to enable automation while allowing to account for the nuances and specifics present in each real-world scenario. (Here’s a look at running logistic regression and using classes).

Conclusion

In short, I was able to develop an efficient model that would do a good job of predicting fraudulent reports as well as identify key warning signs all in the context and framework of a designing what a complete data science project should look like.

Thank you for reading my blog and have a great day.

/close-up-of-thank-you-signboard-against-gray-wall-691036021-5b0828a843a1030036355fcf.jpg)